Luxury Is Dead. Long Live Luxury.

By

3 years ago

The finest products should, by definition, be good for the planet. Indeed, in the future I believe it will be seen as perverse that we ever thought otherwise.'

The luxury industry must radically change if it really wants to embody the age’s aspirations. Mark Stevenson leads a call to arms

Luxury Is Dead. Long Live Luxury.

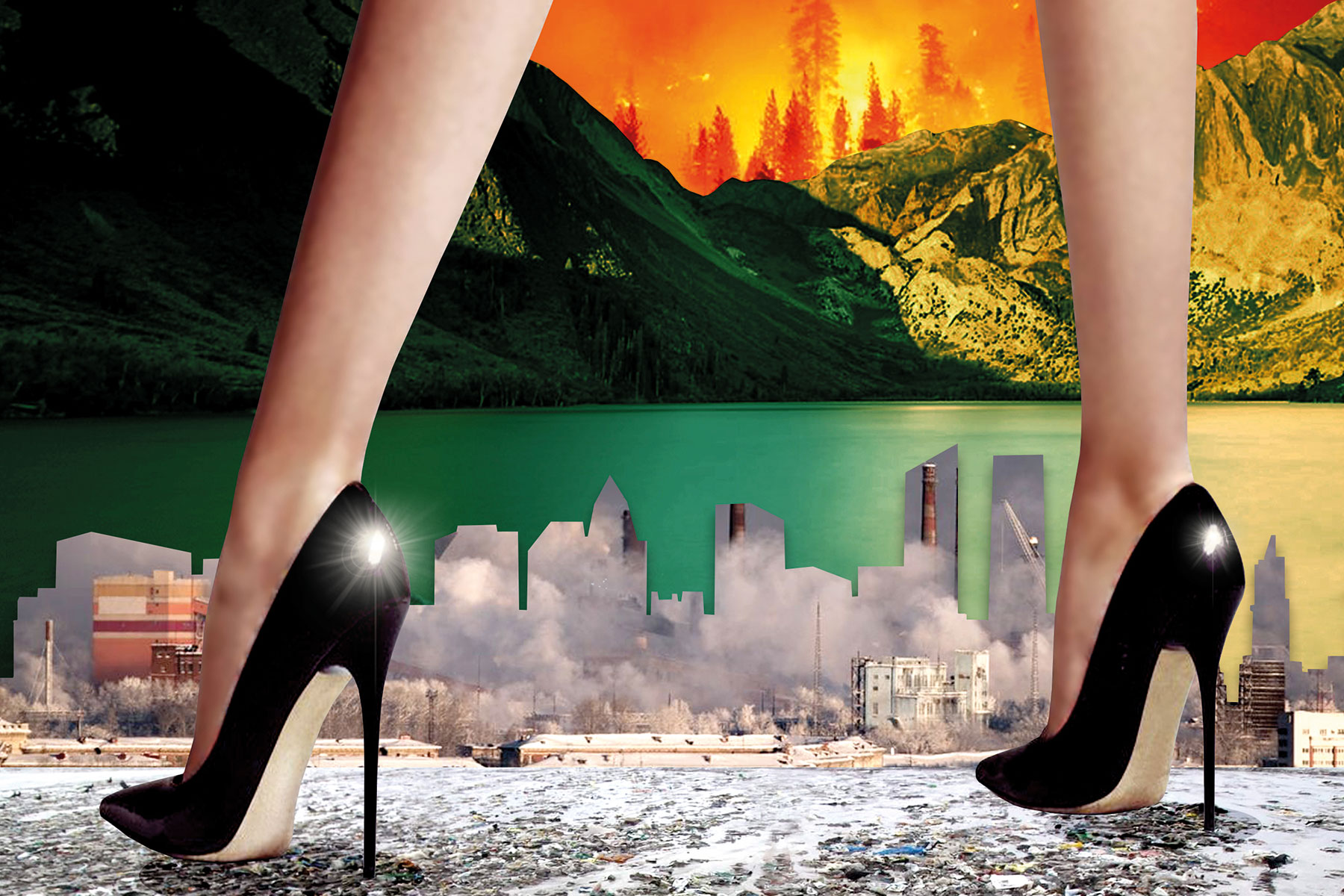

‘So, the world is on fire – and you sell designer shoes at £800 a pair. What exactly is the point of you?’

This was the challenge I put to the full staff of a luxury footwear brand one afternoon a few years ago, a day the news was dominated with stories of Californian wildfires that had turned much of the state into a vision of hell. The scale of the fires was unprecedented, but no longer. We now grimly accept that much of the world is a tinderbox, just one indicator of our broken relationship with our fragile home.

There was an uncomfortable silence in the room. I let it play out. What, I pressed on, was the point of selling footwear that only the most financially privileged could afford (but certainly didn’t need) in the context of the climate emergency, not to mention a world riven with unconscionable levels of inequality? The silence grew in power, as those in attendance looked down at their (no doubt expensive) shoes, shuffled uncomfortably… and offered nothing.

No one had an answer to my challenge, so I relieved them of their gilded misery and told them how they could find relevance and regain a sense of worth in their work – but we’ll come to that later.

The recent IPCC report tells us that changes observed in the climate ‘are unprecedented in thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years’ with and some (including the sea level rise baked into the system) ‘irreversible’. These changes are due to a 1.1°C temperature rise since the industrial revolution, and the direct result human activity. The work we do and the way we consume makes nearly all of us complicit in perpetuating intertwined economic and governance systems that have created this disaster. And most of us, including CEOs and politicians, feel powerless in the face of the embedded status quo.

That complicity and helplessness are a large part of why, according to the Gallup State of the Global Workplace research programme, between 70 and 80 per cent of employees globally feel disengaged from their work. As the corporate world’s sluggish enlightenment creeps forward, everyone from CEOs to the shop-floor employees tell me that their salaries have now become as much bribery to perpetuate the disaster as they are reward for the (damaging) work done. Those horrific engagement stats are also a proxy for a whole host of mental health problems. You don’t need to be a psychiatrist to understand that when your work and your values are at odds you’re going to suffer. This is bad for everyone. Dan Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us puts it well: ‘when the profit becomes unmoored from purpose bad things happen – bad things ethically, but also crappy products, lame services [and] uninspiring places to work’. There’s a huge productivity dividend going begging. Imagine what a genuinely engaged workforce would do for the economy.

Illustration by Aase Hopstock

But there is hope. Covid has given many of us a new lens on the world. As the skies quietened and the air cleared, we began to take stock of our careers and priorities. We witnessed how, when people only buy what they need the economy collapses and wondered, ‘does that make sense?’ We looked anew at the keyworkers who keep our nation going, seeing how they are the most valuable to society, even though we reward them the least – and we felt guilty about it, as we should. We saw how selfish individualism looked ridiculous and unseemly in the face of our communities coming together in the service of one another. We realised that all the money in the world is a poor substitute for an embrace, or even a handshake and that no earthly reward can compensate us for being absent from the bedside of a dying loved one, or the inability to hold each other up at a funeral. Perhaps, most importantly, many of us came to understand that the pandemic was not a random accident, but a symptom, in part, of our damaged relationship with the natural world, and that by association Covid was an ‘amuse-bouche catastrophe’. The main dish, climate change, became larger, not smaller, in our minds. In short, everyone on the planet has been given a lesson in systems, interconnectedness and interdependence. As the pioneering environmentalist John Muir put it, we found out that ‘when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe’.

For luxury brands, selling the concept of exclusivity and opulence, this collective catharsis brings challenges. In a Covid- and climate-changed world almost all the brands in this publication (particularly in light of some of their historical actions) have a problem they cannot ignore. In the wider context of environmental collapse and societal injustice their offerings, if unchanged, look far less like badges of personal success and much more like symbols of our collective failure. If they wish to embody the age’s aspirations, they cannot avoid radical change.

What now?

So, what now for the luxury market? What should the assembled brands in this publication do? How do they re-invent themselves to be relevant in the future we face for, as Philip K. Dick once famously put it, “’Reality is that, which when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away’.

The way forward seems obvious. Luxury brands have always sold themselves on the promise of being the best, the most aspirational, the finest of the fine. In the world we’re all having to build together now, that promise must also mean being the most regenerative and ethical. Luxury brands can and must redefine aspiration. The finest products should, by definition, be good for the planet. Indeed, in the future I believe it will be seen as perverse that we ever thought otherwise. This was the message I delivered to those purveyors of fancy footwear.

The good news is a regenerative agenda is good for you. The research bears it out time and time again. ‘High sustainability companies significantly outperform their counterparts over the long-term, both in terms of stock market as well as accounting performance.’[1] Why? Because such companies live in the real world, they look outwards, and therefore manage risk better. They reduce their own costs by tackling waste and inefficiency. And they have engaged employees whose productivity dwarfs that of less ethical competitors.

But if the carrot doesn’t convince you, perhaps the stick will. The UK has a legally binding Net Zero target for 2050, to be enforced by the Office for Environmental Protection. The courts have already shown their willingness to intervene, one example being the Court of Appeal’s ruling that the government’s policy statement in favour of Heathrow expansion was unlawful, in the light of its climate commitments. Ask yourself: do you think a UK government (of any flavour) is going to let business off the hook when it comes to meeting the national target? For organisations over a certain size, reporting on emissions is already a legal requirement. It won’t be long before reducing those emissions (and permanently removing what is left) will also be mandated by law. It therefore makes cold hard commercial sense to get ahead of that legislation and clean up your act (and see your less enlightened competitors flounder when the laws do pass). Here’s another idea being discussed by certain governments: reduced corporation tax for businesses that advance the UN sustainable development goals (and by the same token, higher bills for those that do not). You know what to do.

Actions luxury brands can take now to stay relevant:

- Join the ‘Race To Zero’, the UN-backed global campaign helping companies, cities, regions, financial and educational institutions “take rigorous and immediate action to halve global emissions by 2030 and deliver a healthier, fairer zero carbon world in time.

- Appoint a Chief Climate Officer to the board with the same standing and power as every other C-suite executive.

- Commit to permanently removing from the atmosphere the emissions you cannot mitigate. This is neither paying someone else not to pollute, nor planting trees that will take years to sequester the carbon you’ve already emitted (if they survive). You cannot ‘offset’ your responsibilities. Instead find the suppliers who can offer verified and permanent ways to remove your emissions and help build the removals market, as enlightened companies like Shopify and Stripe are. Without a permanent removal industry we are all toast.

- Understand that this is your moment to do something fantastic and life affirming. You have the privilege of being alive as we face humanity’s greatest crisis and the ability to do something about it. If, as John Muir said, everything is ‘hitched to everything else’ that means you are connected to everything around you. What you do ripples out across time and space and in this moment of crisis it matters whom you choose to be. To quote the great Jane Goodall, ‘What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.’

Mark Stevenson is a futurist, award-winning author, speaker, advisor and board member helping governments, corporates and third sector clients think beyond this world to better the one we build next

[1] Harvard Business School, ‘The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance’ – Robert G. Eccles, Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim,

Read More Essays

Mission Possible: Making Fashion Sustainable