Artist Martin Wade on the Power of Painting to Overcome PTSD

By

3 years ago

The ex-soldier uses art as a form of treatment

After a decade in the armed forces, Martin Wade was sent to Afghanistan – an experience that affects him to this very day. The artist speaks to Caiti Grove about his subsequent treatment, the lack of mental health support for soldiers, and how painting became his route to recovery.

Artist’s Studio: Martin Wade

Defined form is a way of controlling emotion,’ says Martin Wade, standing next to a canvas where stripes of yellow weave into blue and red to create a joyous matrix of colour. He feels this ordered geometry offers reassurance, ‘unlike free expression, which at the moment would be too chaotic.’

Trained in law, Martin couldn’t imagine life behind a desk for the rest of his career, so joined the army. ‘It sounds rather twee, but I wanted to serve my country.’ He rose to Lieutenant Colonel, and advised on the legal use of force in conflict situations around the world. Back home, he prosecuted at courts martial and was Commander Legal for British Forces in Germany. After more than a decade of service in Northern Ireland, Kosovo and Bosnia, he was sent to Afghanistan.

‘Ultimately it was my undoing,’ he says, matter-of-factly. In 2010, after coming back from Afghanistan, Martin was in Germany when he admitted himself into a psychiatric hospital. It was there he started painting. ‘It was mandatory. You pretty much did what you’re told. When it was time to play table tennis, it was time to play table tennis.’ The art cupboards were quite different from his old secondary school in Wales, though. ‘It was like an Aladdin’s cave. Some cupboards were an entire room full of art material.’

On an easel perched on a desk, Martin finishes his first commission for the army, destined for the Adjutant General Corps, which includes the Military Police and Army Legal Services. His style and use of colour will be a first for an Officers’ Mess, usually decorated with gilt-framed oil paintings of long-dead monarchs, stiff generals, and stylised battle scenes.

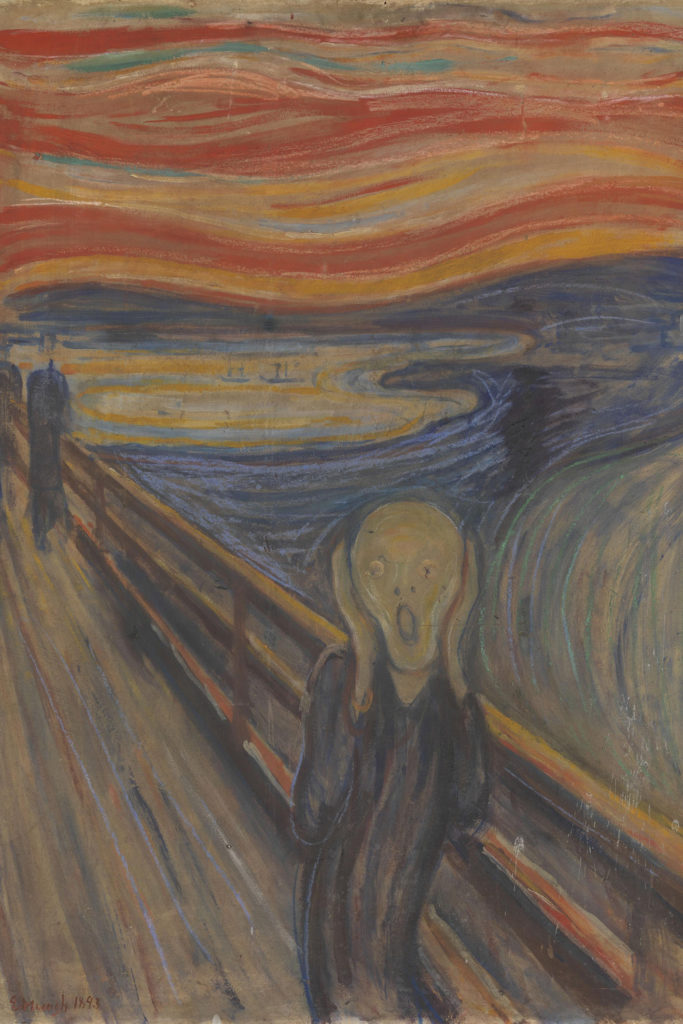

The work is about Martin’s own therapy, and colours swirl across the page like a helter-skelter. During episodes of PTSD, he experiences vivid flashbacks of his experience in Afghanistan, the heat and smells of the hot terrain creating a visceral reliving of traumatic memories. ‘

I was in the therapy room, mentally stuck on the battlefield and couldn’t get back off.’ He has learnt techniques to help him return to the present day. ‘This work is about following a light all the way home, from the bottom right of the canvas to the centre, the present day.’ He painted it in 2018: ‘It was a boiling hot summer – I was sweating like a marine in a spelling test.’

He continues: ‘When you fire to kill, direct an air strike, end another life, or choose not to, it takes something from you. On occasion I did have to pull the trigger or resupply ammunition under heavy fire.’ Yet he has struggled to find support even in the famous Bethlem Royal Hospital. ‘They gave therapy with a hurry-up gun to the head.’ NHS funding was rationed and piecemeal. ‘For the cost of one or two Hellfire missiles, we could be patched up and become effective human beings again, but they leave us to self-recover or rely on charities. The same happened after the Boer War, and the First and Second World Wars; charities had to fill a void the government left. It’s a national disgrace.’

Yet he remains positive for the future. ‘I have faith in common humanity and the mind’s innate ability to mend. That’s where my art will lead me, to recovery, where I can be the best version of myself.’

Find out more about Martin’s work at martinartist.com

READ MORE

Break Out Culture With Ed Vaizey: Listen to the Podcast Today / Conversations at Scarfes Bar: Catherine Goodman