Diversity Is A Must In 2023 If Companies Want To Remain Relevant

By

2 years ago

Adapt to the times or be relegated to the history books

Diversity and brand equity are critical for success but companies who don’t adapt to the times are in danger of losing the value which they hold so dear, says Sir Trevor Phillips OBE ARCS FIC.

Nobody really agrees on what brand equity means – but we know it when we see it. The late Queen had bucketloads, with virtually unparalleled global levels of recognition, combined in her final years with stellar approval ratings for the way she did her job. In defining what it looks like to be British, Sir David Attenborough, the BBC, and latterly English football’s Premier League may not quite fill the gap left by the loss of a beloved monarch, but they count.

Brand equity is vital in telling us who we are. Our iconic British brands are part of a story defining who we’d like to be as a nation. They also carry commercial value because the individual human story is often told through the brand choices we make. For decades I remained loyal to a woefully unreliable British auto marque, spending money I didn’t really have to keep it on the road. I convinced myself that it was a good investment as my friends, family and professional peers would see me as someone from a modest background with aspirations to be a person of refined taste. It’s a matter of identity.

But the world moves on, and the character assets that may have lifted a brand in the past can quickly turn into liabilities. Sometimes they no longer resonate with the prevailing national story; the classic British icons that convey stability, elegance and a hint of exceptionalism – Rolls-Royce perhaps – are no less superb this year than they were 12 months ago, but they jangle discordantly with our current chaotic political reality.

The Queen had brand equity in ‘bucketloads’

More frequently though, the ebbing of a brand’s value lies in its failure to move with a new social reality; and in the 21st century world, no transformation is taking place with greater rapidity and impact than the growth of diversity – both objective and subjective.

The 1980s saw huge changes in the way that money and information moved around the world, and right behind this revolution came a human story. People are on the move. It is thought that today some 400 million people live and work outside the country of their birth. To put it another way, there are probably more people studying, working and doing business with folks who are not like themselves than at any time in human history. Friction abounds, sometimes rising above the level of workplace grumbling to open conflict.

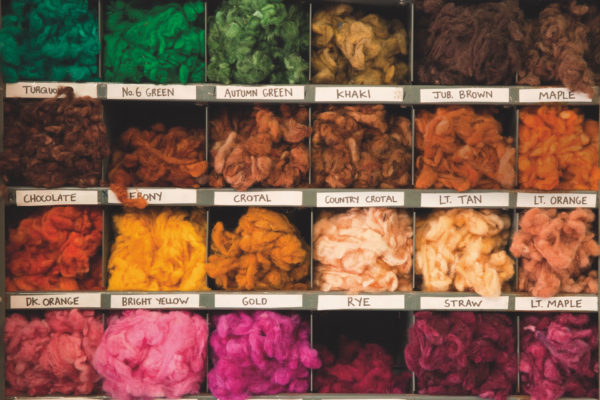

At the same time, the 20th century let the genie of customer choice out of the bottle, turbocharged in the past two decades by the astonishing growth of digital commerce. We can source the garment or gadget that we want in exactly the configuration and colour that pleases us; we can even, at the swipe of a screen, find the life partner with whom we will share our dreams, as well as the mundane reality of hanging out the laundry. Internet dating no longer carries the whiff of desperation for a generation seeking perfection.

It follows that brands need to make ever greater efforts to appeal to a world that is not only more diverse in culture, ethnicity and outlook, but also one in which women, minorities and disabled people no longer expect to have the fact of their difference treated as a flaw to be disguised or ignored. We are less tolerant of brands that don’t ‘get it’. Parents shy away from stereotypical pink and blue toys and clothing. And I doubt very much that cosmetics with names like ‘Black-Up’ (it does exist) are likely to catch on in the English-speaking world.

Then there are demographics. Between now and mid-century anyone trying to sell anything to the USA will have to contend with the fact that a minority of adults there will be white; despite their higher average wealth and buying power, you can’t sustain sales on half the market.

Here in the UK, Indian-heritage households – the largest minority – already out-earn the average by some 20 percent; they have disposable income and they want choice. By mid-century up to a third of Britons will be people of colour. As one corporate leader told us: ‘if we don’t have a multicultural strategy we don’t have a growth strategy.’

Work we conducted on the UK’s free-to-air broadcasters in 2016 showed that even the best – the BBC – could no longer count on the loyalty (or inertia) of much of its audience. In a choice environment impervious to price, minorities were almost half as likely to tune into its most popular news bulletins; they preferred a view of the world from a different perspective offered to smaller, targeted audiences.

Some of our more successful brands tend to assume that they can leave responding to these trends towards fragmentation until later, believing that the power of their presence in the market will, for the time being, transcend the plethora of options. They would be wrong. In many of the businesses that my teams work with, the modern problem is not that customers are wearied by choice; it is that they can usually find a brand they think is consistent with their own chosen identity far more easily than before – and factors other than price and value figure highly in their decision-making. That is why our data analytics arm provides detailed data to major fast-moving consumer goods brands on matters like, for example – and I am not making this up – which specific skin foundation women from Gulf states prefer. Having this data makes an appreciable impact on revenues.

There is a further issue that brands will need to confront: the growing significance of intermediaries. I have a niece who, as far as I can see, makes a rather better living than I do recommending athleisure to her million or so Instagram followers. Issues such as corporate performance on climate change or sexual violence clearly matter commercially; nobody wants to be associated with brands whose stars beat their wives. Influencers won’t advocate for brands that don’t recognise diversity and customers don’t just buy what they see in real or virtual shop windows; they worry about what’s behind the door marked ‘staff only’ .

The risks of not addressing diverse markets are manifold and manifest. But so are the advantages of getting it right. I spend much of my life as chairman of a firm that puts talented people into executive and board roles in big companies. In the war for talent, a brand’s good reputation can be worth almost as much as an extra ten percent in the pay packet. This isn’t just an issue for women and minorities. Today, not even the most hard-bitten white, male, middle-aged corporate leader wants to tell his family that he works for a firm with a reputation for achieving success by ignoring the harassment of female employees or failing to promote capable minority executives.

These stories get around; there’s a reason why internet employment sites like Glassdoor are successful. Few narratives sully a brand faster today than the sense that it has failed to pay due regard to diversity and inclusion. And in case you want to know why people put the ‘D’ and the ‘I’ together, think about it like this. Companies have to make sure that their culture is ready to accept people as they are; or else top performers will go somewhere else. The days of demanding that everyone fit into the company strait jacket are probably over for good.

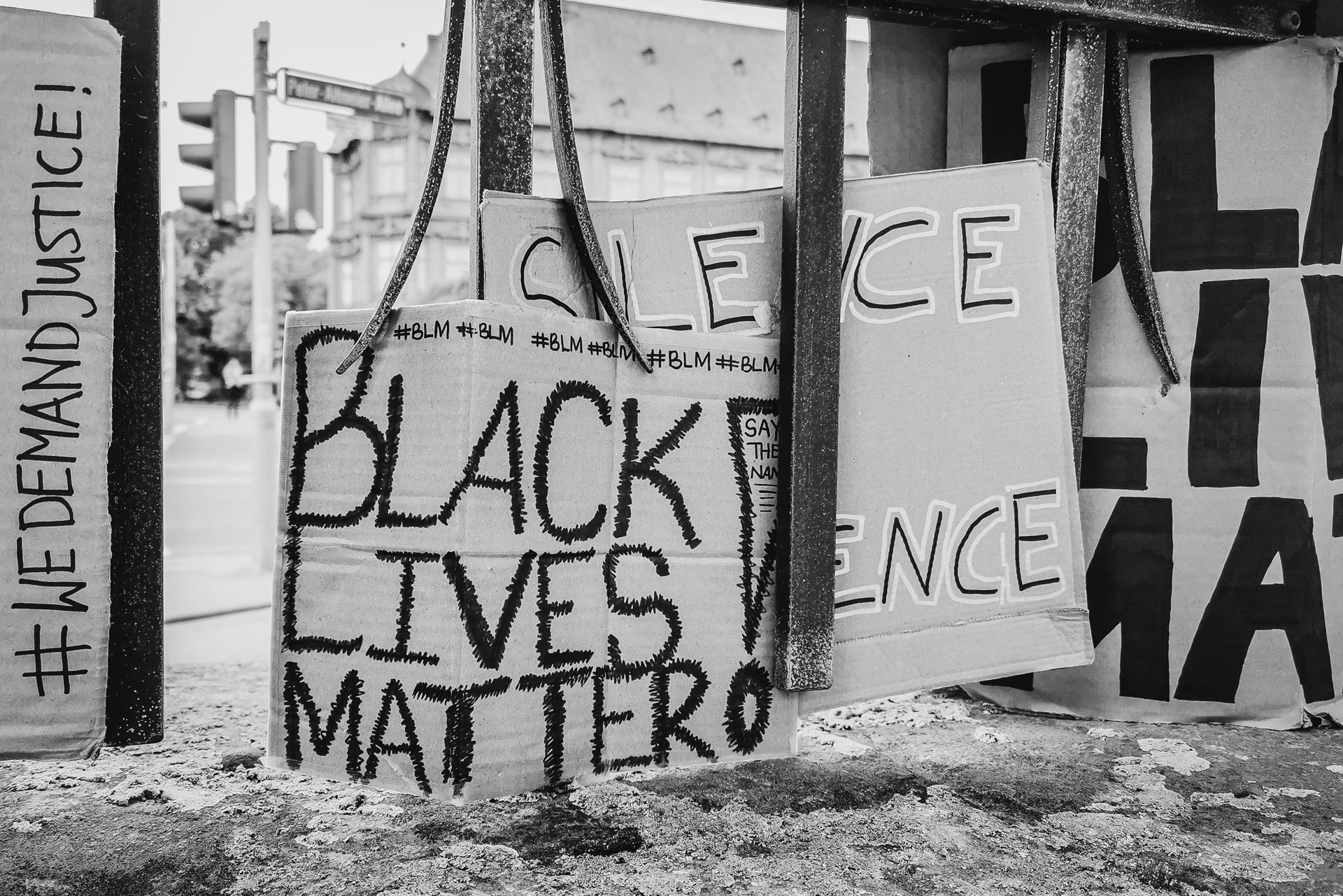

‘While Black Lives Matter woke many brands up to diversity in 2020, some are now paying the price of having talked the talk, but two years on, not having walked the walk.’ Image via Unsplash

All this means that brands need to adapt to what ‘good’ looks like for employees. Boards and CEOs will need to get used to colleagues who don’t share their ideas about raising families, or about the balance between money-making and brand-building, for example. It will be hard but necessary for everyone to think differently. We don’t just need to tinker with the colour of faces around the table, or raise the number of those who wear skirts. We need to provide a space for everyone to bring their whole personality to work.

Most of all, while Black Lives Matter woke many brands up to diversity in 2020, some are now paying the price of having talked the talk, but two years on, not having walked the walk. Firms already have to report the pay gap between men and women; soon that requirement will be extended to ethnicity.

It’s hard to imagine a firm that doesn’t treat all its own people equally is being truly fair to its suppliers, its clients and customers. Nothing destroys brand equity faster and more completely than a yawning gap between promise and the reality. In these difficult times, what you say must turn out to be what you do.

Illustration: Kamo Frank