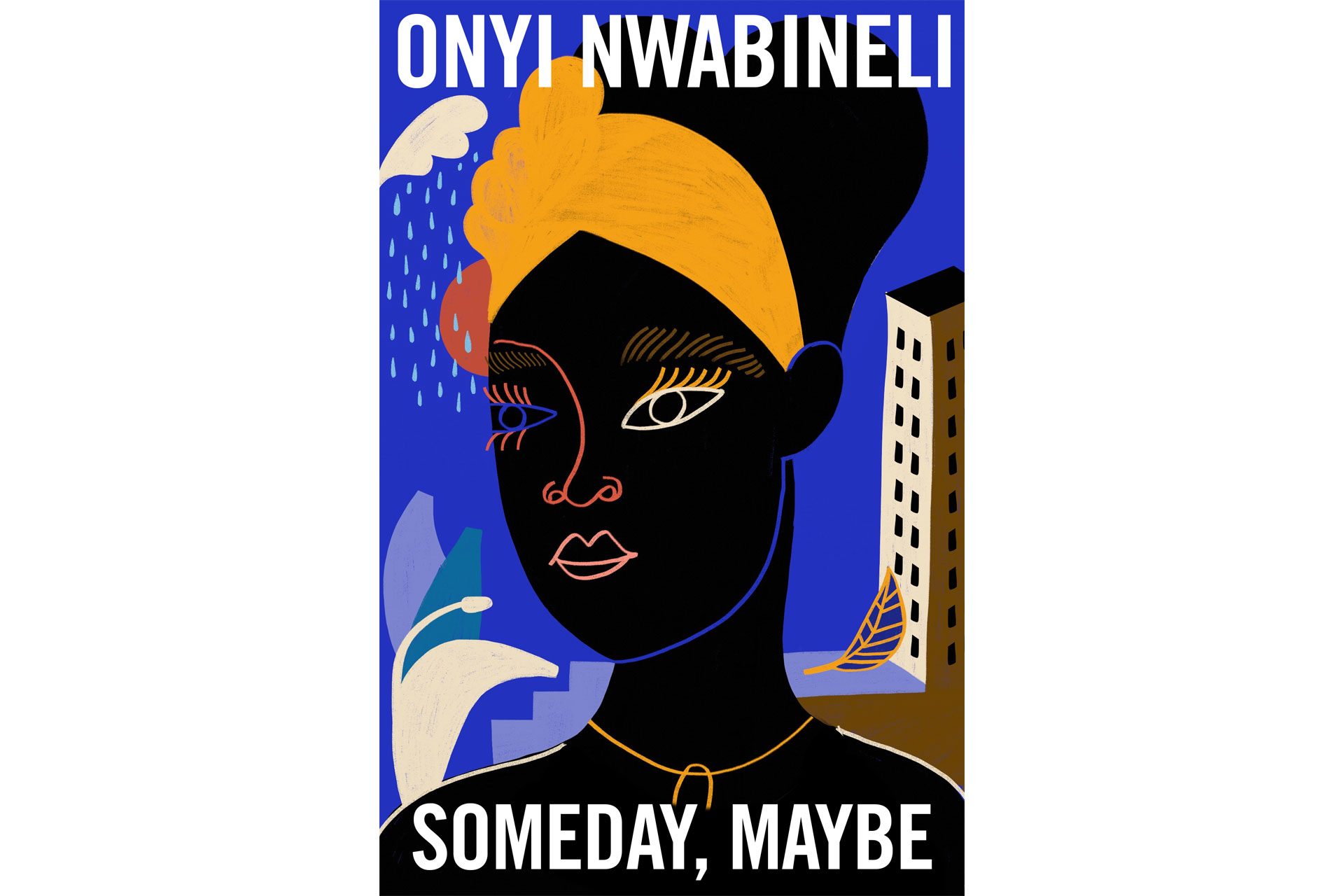

C&TH Book Club: Someday, Maybe by Onyi Nwabineli

By

2 years ago

Grief and humour interplay in 'Someday, Maybe'

In December’s Book Club, Onyi Nwabineli tells Belinda Bamber about the influence of her Nigerian heritage in her novel about love and loss, Someday, Maybe.

Interview With Onyi Nwabineli, Author Of Someday, Maybe – C&TH Book Club

Belinda Bamber: ‘Someday Maybe’ has been published as your debut novel. At what age did you start writing stories?

Onyi Nwabineli: I started writing stories as soon as I was able to hold a pencil and formulate words! My parents like to joke that even before I could write, storytelling was my escapism of choice. But pencil to paper? Maybe about five or six.

BB: Did you have a clear idea of the story when you began writing? How did it develop?

ON: I had no idea of the plot when I initially began writing the story. The book is a love letter to a friend who also lost her husband, and I started with the grief first and moved onto character creation and finally a plot. I don’t think I would do it that way again – I need some kind of plan!

BB: You achieve the rare feat of balancing grief with humour – did that distinctive voice come naturally?

ON: I think so. Culturally, we are extremely adept at infusing humour into even the saddest situations. It brings us together and reminds us that laughter is a form of healing. It made sense to me to inject humour into Someday, Maybe for that reason and also because with such heavy subject matter, readers would be thankful for some lighter moments.

BB: First novels often reflect the dictum to ‘write what you know’ and this book reverberates with a deep understanding of loss. Can you share any personal experiences?

ON: I think everyone will be touched by loss and grief at multiple points in their lives. The book is a culmination of having lost loved ones myself (aunts, uncles, friends) but also watching those I love navigate grief themselves. It is such a uniting experience even though it can feel very lonely at times.

BB: Can fiction help us to understand or come to terms with trauma? Have any novels helped you?

ON: I think the phrase ‘art imitates life’ is so apt when it comes to this. I believe fiction can be a wonderful tool to help people first identify what it is they are feeling or going through, and then begin to navigate it. Seeing your experience mirrored on a page in front of you can be such a lightbulb moment and many readers have already reached out to me to say ‘thank you. It’s like you wrote this for me. This is exactly how I felt,’ and there is no greater gift for an author than that, in my opinion. A couple of novels that have helped me are Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson and The Astonishing Color of After by Emily X.R. Tran.

BB: The title gives hope that ‘someday, maybe’ Eve will be able to move on. She’s rich in the support of strong, dry, funny women like her sister Gloria and friends Bee and Luisa. Would you describe yourself as an optimist?

ON: I am an optimist in some things but I probably would describe myself as the Smiling Misanthrope. That’s awful, isn’t it? I have a wonderful circle who mean the entire world to me, but if it’s not them or my family, you can usually find me in pyjamas avoiding the world.

BB: There’s a satisfying nineteenth-century story arc, of a heroine who learns from experience and gains in courage and self-reliance. Which stories nourished you growing up?

ON: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca remains one of my favourite books of all time. Alongside Wally Lamb’s I Know This Much Is True. They taught me some interesting lessons and opened my eyes to a lot about the world. I would say one of the most important stories for me is Things Fall Apart by the amazing late Chinua Achebe.

BB: One of the joys of this novel, for me, was the sense of family love and loyal friendship that cradles Eve and helps her back on her feet. Does this reflect your own life and values?

ON: Oh absolutely. I am such a lover and champion of community and love in all its forms. It is so important and I think this world would be much shinier if more of us understood the value in friendship and community building. It’s the bedrock of my entire life.

BB: There’s also the sense that Eve is the slightly spoiled and adored baby of the family. Does that reflect your sibling experience?

ON: If you ask my older siblings, they might say that for a couple of years, that was the case! But to be honest, I don’t even feel like the baby of the family. Sometimes, I feel older than my big brother and sister!

BB: How do you fit a writing routine around a full-time job?

ON: I have absolutely no idea. But seriously, I do not write as much as I would perhaps like to. I am becoming far more strict about carving out time to write and that means bowing out of certain social bits and pieces when it comes to crunch time, and limiting my Netflix consumption. I need routine otherwise I won’t write a word. But it isn’t easy at all!

BB: How was the experience of finding a publisher? What advice would you offer to other writers trying to get their work out there?

ON: Research, research and more research. I started out researching literary agents and agencies first and that is what I would encourage writers to do. Having the right agent makes the process of finding the right publisher a hundred times easier. Amy, my agent, is a literal godsend. I don’t second guess anything she tells me. And working with her made advocating for myself that much easier when it came to deciding who I wanted to publish my work. Look at other authors and similar genres that publishing houses have put out there. Think about if your work would fit. Start there and do not be scared to ask questions.

BB: You recently founded Black Pens, a successful writing retreat that’s supported with an Arts Council grant. What’s scheduled for 2023?

ON: If I have my way, I will be running two retreats in 2023 – one in summer and one in autumn. It all depends on timing and funding and this still won’t meet demand but I am trying to take it one day at a time and grow at a sustainable pace.

BB: Black Pens is ‘for Black womxn and femmes’. Given the continual redefinition of gender terms, who does that include? How do you personally navigate the difficulties and polarisations of cancel culture and the trans debate with friends and colleagues? And what advice would you give to readers who are anxious and confused?

ON: Black Pens is for cis and trans women and non-binary femme-presenting attendees. When it comes to cancel culture, I basically opt out of the conversation as much as I can because I simply don’t believe it is a real thing; if it was, I don’t think I would hear so much from the reportedly ‘cancelled’. And yet.

I uplift trans voices, do my reading in order to learn more, ask questions if I am confused and encourage anyone feeling similarly to do the same. I will always be on the side of inclusivity but I am aware I can’t make up the mind of anyone but myself.

BB: The story references the need for strength when bringing up children of colour or mixed race in the UK’s predominantly white community. What is the way forward, individually and collectively, for all of us in trying to create a society for our children that embraces all colours and cultures – ideally in the unconditionally accepting spirit that Eve’s family embraces her?

ON: The outright rejection of racial discrimination in the myriad ways it manifests is the only way to create a safe and inclusive society for our kids. And that starts with acknowledging the problem and understanding that racism is insidious, and bias goes undetected or unacknowledged much of the time. We spend a lot of time in the UK, debating whether or not racism actually exists here instead of tackling it, and sadly, I still think we have a long way to go, but I still have hope (see, the Smiling Misanthrope strikes again.) A lot of it is rooted in (sometimes irrational) fear and ignorance, but it is 2022 and that excuse has been driven into the ground at this point.

BB: Eve and her parents and siblings sometimes use Igbo phrases to each other, which strengthens the sense not just of their Nigerian culture but also, more universally, of the private shared language of every close-knit family. It also suggests that some phrases just can’t be adequately translated into English. What do you find are the strengths and limitations of English as a language for writing?

ON: English is the most spoken language in the world, I believe, so there’s always going to be an advantage to being able to communicate in the language – you are able to reach more people and hopefully have your writing resonate with a greater audience. Plus, there are just some amazing English (and British) colloquialisms that brilliantly capture emotions and frustrations. But it is as you have said, there sometimes aren’t words that can be used to adequately translate some of the nuances of other tongues, and that can be frustrating, because you do want readers to know exactly what it is you’re saying to them. I am a fan of the glossary for this very reason. I think there are ways we can avoid things being lost in translation.

BB: There’s an outstanding rollcall of Nigerian writers who’ve impacted contemporary British culture, of which Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri and Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie are some of the best-known. There are also several exciting new voices emerging. What does that heritage mean to you as a Nigerian-British writer?

ON: My heritage is everything. There are such rich and expansive customs, rites and traditions within our culture that our parents and grandparents have worked hard to preserve as best they can even as scattered they are across the diaspora. It’s grounding to have ties that bind outside of familial bonds, and preservation is something I think we should continue to strive for in our own ways. It’s why I think everything I write will have elements of Igbo culture woven through it. It’s who I am.

BB: Were any Nigerian writers taught in the classroom when you were growing up in Britain, and if so, was the method of teaching a positive or negative experience?

ON: Unfortunately, no Nigerian authors were taught in my English classrooms growing up which was a shame but only encouraged my parents to ensure that they introduced us to Nigerian writers and literature at home. It’s definitely something that shaped my relationship to words, experiences and literature, and I was able to request Nigerian authors in my school libraries as a result.

BB: Which authors currently inspire you and which beloved books are you sharing as gifts this Christmas?

ON: Akwaeke Emezi is honestly the one who aces it for me. Their work-rate and the quality of their work is outstanding. I can only aspire. I also adore Laurie Frankel, Toni Morrison, Fredrik Backman, Benjamin Alire Sáenz and Hanya Yanagihara. I am gifting In Every Mirror She’s Black by Lola Akinmade Akerstrom, Dear Senthuran by Akwaeke Emezi and The Bread The Devil Knead by Lisa Allen-Agostini. All books which stayed with me this year.

BB: You’re the co-founder of Surviving Out Loud, please tell us more.

ON: We started Surviving Out Loud to provide survivors of sexual assault with tangible, fiscal support for therapy, legal expenses and temporary relocation. Therapy especially was the key goal for SOL, meaning that survivors were able to start or continue on their journeys of healing post-trauma. It highlighted the need for ongoing help for SA survivors and we hope to continue the work next year.

BB: Finally, many congratulations on your novel. You’ve been hailed as ‘one to watch’ – when can we look forward to your next book?

ON: Thank you so very much! I am currently working on Book 2 and hope to wrap up in 2023 sometime, so watch this space and I hope to have it to readers as soon as possible.

‘Someday, Maybe’ by Onyi Nwabineli is published by Oneworld, £16.99