Is Game Our Solution to Sustainable Meat Consumption?

By

2 years ago

A meaty question

Tessa Dunthorne is back on the meat. But how to eat it with integrity and the planet in mind? Perhaps it’s by heading to the wild side…

Why Game Meat Is Back on the Menu

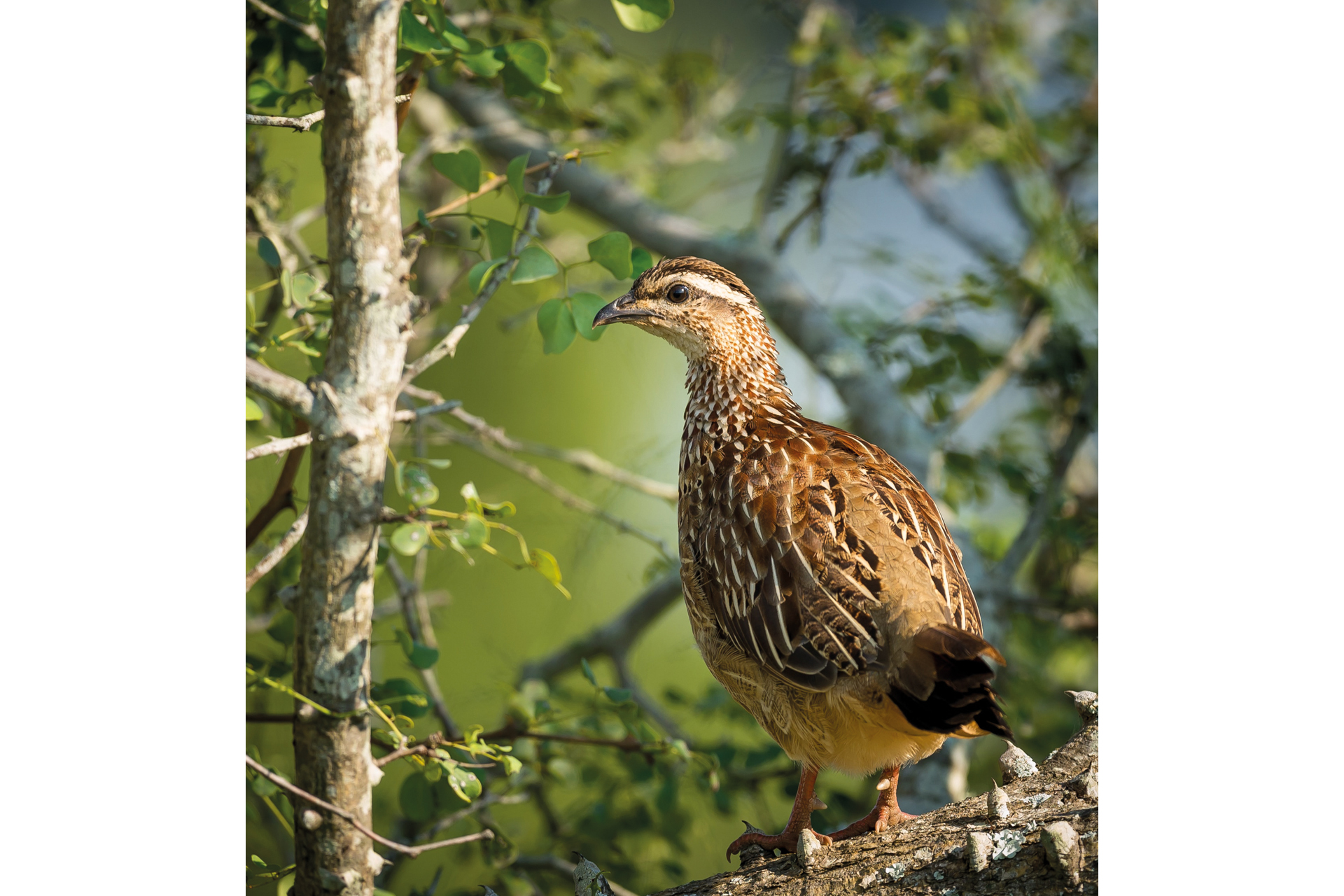

Is eating partridge better for the planet than eating chicken?

I recently began eating meat after a five-year hiatus. Bleeding heart vegetarian though I was – I’d gone veggie after a visit to a Greek meat market – I was always a bit reluctant about it. Not because of the usual barrage of excuses (‘but bacon is nice’, etcetera) but simply put, because it’s hard. Being off the animal stuff, you’re constantly chasing macros and minerals in a bid to manage your nutritional needs. I wasn’t particularly good at this chase, so it’s no surprise that, half a decade later, a visit to the doctor was met with an urgent need to change my diet after one read of my iron levels.

However, there’s no doubt that we shouldn’t be eating as much meat. Avoiding animal products is, according to the scientists behind a 2018 mega study, ‘the single biggest way to reduce your impact on planet Earth’. The meat industry is responsible for over a fifth of all global greenhouse gas emissions, and it’s been proved to have a far greater environmental footprint than plant-based food.

According to the UK’s Climate Change Committee we need to collectively cut our meat consumption by 20 percent to hit ambitious carbon reduction targets. What’s more, a recent study by the University of Oxford found a high meat-eater produces an average of 10.24kg of planet-warming greenhouse gases each day, whereas a low meat-eater (whose daily intake is 50g or less) produces almost half that at 5.37kg per day.

Collectively, as a nation we seem to understand the need to cut down on our meat consumption – a third of Brits set about to reduce their meat-eating at the beginning of this year, many motivated by the environment, and then some by ethics.

Yet the global meat industry is likely to reach record highs and grow by 1.4 percent throughout 2023. So it appears that we’re all a bit confused – our values and our behaviours aren’t quite in total alignment. Is it possible that we’re all looking for a bit more of a compromise, much like my own concession to my body’s nutritional needs? We still want (and in my case, need) to eat meat, but we want to eat it better, more ethically, more carefully.

I’m not going to ask you to break up with bacon, say sayonara to steak, or chide you for your chicken wings. That would require a fundamental habit shift that most of us aren’t willing to make and, frankly, you’d take me for a preachy ex-vegetarian. But there might be a bridging solution for diehard carnivores that’s a little more local, a little kinder – and that has the potential to address vital ecological issues on our shores. I’ll let you make up your own minds. Enter: game meat.

In theory, it’s a neat answer to more sustainable meat consumption. As Elystan Street chef and co-owner Phil Howard says, ‘It’s a no-brainer, given that it is so abundant in this country.’ And yet 72 percent of us currently don’t eat it. Why is that?

Most pheasants have been imported from France as eggs or chicks

From a nutritional standpoint, it makes sense to eat game meat. According to scientists writing for Meat Science journal, wild-shot meats have a ‘very good chemical composition’, thanks to a good balance of saturated fatty acids and a high protein content. The British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) points out that game meat is especially rich in omega-3s, iron, vitamins E and B6, beta carotene, zinc, and selenium.

Its carbon credentials are also good: The Vegan Society estimates that game meat is responsible for a quarter of the amount of CO2/kg versus untrimmed beef. Then there’s its benefit to the countryside – wild venison, in particular. The UK’s deer population is currently believed to be at its highest level for over 1,000 years, thanks to both a decrease in culling during the pandemic and a lack of apex predators. Farmers are reportedly concerned about the havoc herds of deer can wreak upon their crops – causing £4.3 million a year in damages to cereals the country over – and conservationists report that deer harm ancient trees and trample habitats. They’re so prolific, in fact, that Forestry England provided 5,000kg of venison meat to food banks in Devon and Cornwall, as a solution to the cost of living crisis.

But are there any downsides? ‘There’s definitely a preconception that it’s harder to cook,’ says chef Theo Clench of Cycene. ‘You’ve got to be much more delicate about it as there’s very little fat covering on wild animals – they tend to dry out quicker.’ (See overleaf for expert tips on how to cook game). There are also some supply issues. ‘Since the bird flu outbreak, people are shooting less season to season,’ says Theo, ‘and it’s quite hard to get hold of the rarer birds sometimes, like woodcock or snipe, as they’re not bred to be shot.’

Also, the majority of our pheasants and partridges are brought over from France (20 million of the former in 2019, eight-ten million of the latter), and introducing non-native species on such a mass scale has potentially serious consequences: DEFRA reported that areas where foreign pheasants had been sighted were less likely to have certain species of butterflies, due to pheasants eating the caterpillars. And there’s a damage to the wild British bird population, too: according to DEFRA, the antibiotics used in game bird rearing has in the past caused antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains to infect our already-struggling native birds.

And then there are the risks associated with lead. While a hearty venison stew might be packed with vitamins, it might also come with a spoonful of lead shot. ‘You can do plenty of due diligence,’ says Theo, ‘but we always have to warn our guests that a pellet might get through.’ The UK government is expected to ban the use of lead bullets in game shoots by the end of this year or next, but a lot of game meat is currently shot with lead – although the majority of it is typically removed at the point of preparation by a butcher, which does reduce potential lead poisoning risks.

So, should we shun our free-range meat boxes in favour of the wilder side of the butcher’s block? Our best bet is to make considered choices while game is in season (see what’s available when overleaf). As Theo adds, a lot of the questions we have around game meat are the same as we have for any meat – and the answer is much the same, too. ‘It’s down to traceability,’ says Theo, ‘the right suppliers and gamekeepers are careful with lead bullets, they manage the land with conservation in mind, and they protect their [game] numbers. It’s the same as you’d face with fish, or farm-meats.’