Is The Climate Crisis Changing Britain’s Property Market For Good?

By

1 year ago

How the property market is hotting up

What are home buyers looking for in the midst of the climate crisis? asks Anna Tyzack

Is The Climate Crisis Changing Britain’s Property Market For Good?

Getty Images

The British love making small talk about the weather, but in an era of climate consciousness it’s set to become the biggest deciding factor when buying a house or apartment. A study by the Crowther Lab in Switzerland shows that in 30 years the climate in London will resemble Barcelona today, while Edinburgh will feel like Paris, which sounds pleasant enough until you factor in that these rising temperatures will be coupled with extreme weather systems such as prolonged heatwaves, cold snaps and torrential rain.

Indeed, research by Bayes Business School’s Real Estate Centre suggests that one in six properties in England will be at flood risk by 2050. The property landscape could thus look very different, with buyers choosing to settle in Cheshire and Merseyside, which are at the lowest risk of climate damage, and avoiding counties such as Kent and Somerset, where damage is more likely.

In the West Country, Knight Frank is already witnessing climate consciousness among buyers. ‘Progressively buyers are engaging with structural engineers before going ahead with a purchase and we’re seeing hilltop properties and those on high ground holding their value and in some cases commanding a premium compared to those that might in the future be at risk,’ says Louise Glanville of Knight Frank.

For the time being, however, climate consciousness within the housing market is still largely centred on how rather than where we live. As it stands, the housing sector contributes to around 40 percent of the UK’s carbon footprint and greenhouse gas emissions, which means we all have a duty to make our homes more sustainable. Rushing out and installing air conditioning units to cool our stuffy homes will only make the situation worse. ‘As one of the biggest contributors to the problem, our industry can also make the biggest difference – it’s only right that climate consciousness influences every aspect of the market,’ explains interior designer Katharine Pooley.

Buyers, according to Flora Harley of Knight Frank Research, are getting the message: they’re more interested in how buildings perform in terms of energy efficiency and withstanding extreme weather. They want to know, she says, not just how they will perform in the future but how they perform now as it takes substantial investment to improve efficiency and resilience to heat and cold. This is why the once-derided EPC certificate is gaining weight during the selling process, says Matthew Morton-Smith of Tedworth Property. ‘Buyers take the suggestions and considerations more seriously in order to make their homes more environmentally friendly and energy efficient,’ he says.

It won’t be long before EPC ratings are a deal breaker. Already around 59 percent of homebuyers are willing to pay more for a property where at least 75 percent of its energy comes from renewable sources, according to figures from Savills. At the top end of the market developers have been pioneering sustainable building practices and green energy systems for some time. The new Chelsea Barracks neighbourhood in London, where properties cost from £3.3 million, is constructed of Portland whitbed from the Jurassic Coast, a long-lasting and energy efficient building natural stone; there’s a centralised energy system, removing the need for disruptive future retrofits in individual homes, as well as green roofs and grey water recycling systems. It’s one of only 16 schemes in the world to be awarded the green building certification LEED Platinum and is proof that with careful planning, a whole neighbourhood can be built and run sustainably.

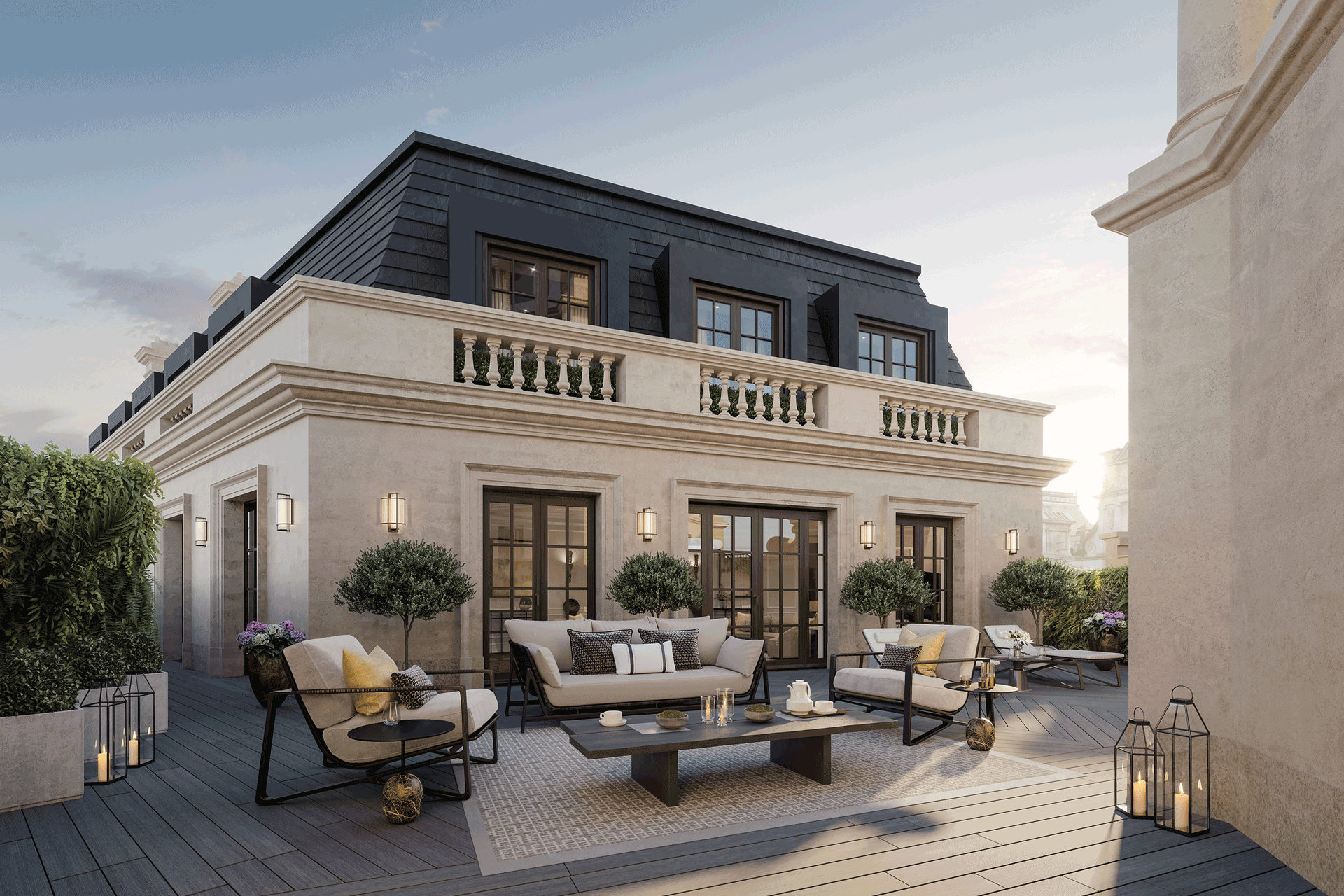

Image courtesy of The OWO

It’s not the case that Britain’s housing stock should be flattened to make way for this kind of development, though. Older buildings might have poor EPC ratings but knocking them down creates dangerous emissions – far more than is saved by replacing them with sustainable modern buildings. ‘Our buildings have a significant amount of locked-in carbon, which is wasted each time they get knocked down to be rebuilt, a process which produces yet more emissions,’ explains Philip Dunne MP, chair of the Commons’ Environmental Audit Committee. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) estimates that 51 percent of the lifecycle carbon emissions from a typical residential premises occur before the building is first used, suggesting it will be decades before the carbon debt is repaid.

At The OWO, Churchill’s former war office in Whitehall, which opened as London’s first Raffles hotel and residences this summer, developers have proved that it is possible to futureproof crumbling period architecture on a grand scale. They retained the majority of the stone façade, reused steel trusses and recycled concrete as hardcore. The modernised structure was then fitted with high specification glazing and insulation, energy efficient lighting and a fresh air ventilation system. In the future the building has the ability to be connected to the district heating system in Whitehall, further reducing carbon.

Athelhampton, a Grade I listed, carbon neutral building

The residences, which cost from £5.8 million, have been designed to be timeless and durable. ‘Short-lived trends are over; people want timeless elegance that will last for generations, which means avoiding non-biodegradable furnishing and choosing natural finishes and weaves,’ says Pooley, whose sustainable design ethos informed the interiors at The Gainsborough, an £18 million penthouse at 9 Millbank, a renovated Grade II listed apartment building in Westminster. Meanwhile in Dorset, heritage architects SPASE Design have transformed Athelhampton, a Grade I listed Tudor stately home, into a carbon neutral building, eliminating 100 tonnes of CO2 per year and saving the owners a six-figure energy bill.

‘Old buildings need to breathe and so many modern materials are just not suitable; by installing renewable technologies, however, you can hugely increase the sustainability and improve running costs,’ explains Managing Director of SPASE Stefan Pitman. The barrier, of course, to adapting period buildings like this will be the cost: even to bring the EPC rating of a £500,000 London house from D to C costs around £15,000; the owners of The OWO are estimated to have spent around £500 million. Yet Marc Schneiderman of Arlington Residential is confident that at least at the top end of the market buyers and developers are prepared to spend more for the sake of the environment. ‘It’s a mindset as much as anything,’ he says. ‘We can all control our carbon footprint and reduce energy wastage. My clients are increasingly fitting properties with meters to inform them of their daily energy consumption and installing efficient irrigation systems to monitor and reduce water usage outside. It’s about finding ways to make our homes tackle the cause.’