Who Is Han Kang?

By

1 year ago

Introducing the new Nobel Laureate

The Swedish academy has awarded the next Nobel Prize in Literature, commending ‘outstanding work in an idealistic direction’. And, in 2024, we have our first ever South Korean writer, and 18th woman to win the prize since it was created in 1901: Han Kang. So who is she? And where to start with her work?

Who Is Han Kang?

Han Kang is a South Korean writer born in Gwangju in 1970. She studied Korean literature at Yonsei University, before enrolling in an International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in 1998, writing and publishing poems and short stories in literary magazines as well as novellas in the interim.

Han’s first novel, titled 검은 사슴 (‘Black Deer’) was published in 1998 in Korea, and a number of novels followed, including 채식주의자 (‘The Vegetarian’) in 2007. A film adaptation of the latter was released in 2009, written and directed by Lim Woo-Seaong, but international attention didn’t come until 2015 when The Vegetarian was translated into English by Deborah Smith. This caught the attention of readers across the globe, but especially the Booker Prize.

In 2016, Han was awarded the International Booker Prize for The Vegetarian, after being the first Korean writer to ever be nominated. The New York Times Book Review also listed The Vegetarian – which traces the fallout of a woman’s decision to become a vegetarian after a gory nightmare – as one of the 10 best books of 2016. The novel also caught the attention of the Swedish Academy, though we wouldn’t know it until now.

This international success prompted more of Han’s work to be translated into English: Smith translated 소년이 온다 (‘A boy is coming’; 2014) into Human Acts in 2016, 흰 (‘White’; 2016) into The White Book in 2017, and 희랍어 시간 (‘Greek language lesson times’) into Greek Lessons in 2023, with 작별하지 않는다 (Don’t say goodbye, 2021) being published as We Do Not Part in 2025.

The Nobel Prize In Literature 2024

Han Kang has been awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature ‘for her intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life,’ the Academy says. Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel committee, added Han’s ‘empathy for vulnerable, often female, lives is palpable, and reinforced by her metaphorically charged prose. She has a unique awareness of the connections between body and soul, the living and the dead, and in a poetic and experimental style has become an innovator in contemporary prose.’ The Vegetarian is believed to be the main impetus for awarding Han the prize.

Upon a phone call from the Swedish Academy informing her of the news, Han said: ‘I’m so surprised and absolutely I’m honoured. I grew up with Korean literature, which I feel very close to. So I hope this news is nice for Korean literature readers, and my friends and writers.’

The news has captured the attention of South Koreans worldwide. In a statement, Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol congratulated Han, saying: ‘You converted the painful wounds of our modern history into great literature. I send my respects to you for elevating the value of Korean literature.’

An Introduction To Han Kang’s Books

Five of Han’s works have been translated into English. They are:

The Vegetarian

A three-part parable delving into the fallout of a Korean woman becoming a vegetarian after a gory dream.

‘Yeong-hye and her husband are ordinary people. He is an office worker with moderate ambitions and mild manners; she is an uninspired but dutiful wife. The acceptable flatline of their marriage is interrupted when Yeong-hye, seeking a more ‘plant-like’ existence, decides to become a vegetarian, prompted by grotesque recurring nightmares. In South Korea, where vegetarianism is almost unheard-of and societal mores are strictly obeyed, Yeong-hye’s decision is a shocking act of subversion. Her passive rebellion manifests in ever more bizarre and frightening forms, leading her bland husband to self-justified acts of sexual sadism. His cruelties drive her towards attempted suicide and hospitalisation. She unknowingly captivates her sister’s husband, a video artist. She becomes the focus of his increasingly erotic and unhinged artworks, while spiralling further and further into her fantasies of abandoning her fleshly prison and becoming – impossibly, ecstatically – a tree.’

Paperback, £9.99, Granta Books

The White Book

A poetic meditation on the colour white.

‘The White Book is a meditation on colour, beginning with a list of white things. It is a book about mourning, rebirth and the tenacity of the human spirit. It is a stunning investigation of the fragility, beauty and strangeness of life.’

Paperback, £9.99, Granta Books

Human Acts

A controversial novel dealing with the May 1980 Gwangju uprising and the death of the young boy Kang Dong-ho, expanding from the ‘80s to the present day.

‘Gwangju, South Korea, 1980. In the wake of a viciously suppressed student uprising, a boy searches for his friend’s corpse, a consciousness searches for its abandoned body, and a brutalised country searches for a voice. In a sequence of interconnected chapters the victims and the bereaved encounter censorship, denial, forgiveness and the echoing agony of the original trauma.’

Paperback, £9.99, Granta Books

Greek Lessons

A novel about language and human connection.

‘In a classroom in Seoul, a young woman watches her Greek language teacher at the blackboard. She tries to speak but has lost her voice. Her teacher finds himself drawn to the silent woman, for day by day he is losing his sight.

‘Soon they discover a deeper pain binds them. For her, in the space of just a few months, she has lost both her mother and the custody battle for her nine-year-old son. For him, it’s the pain of growing up between Korea and Germany, being torn between two cultures and languages.’

Paperback, £9.99, Penguin Books

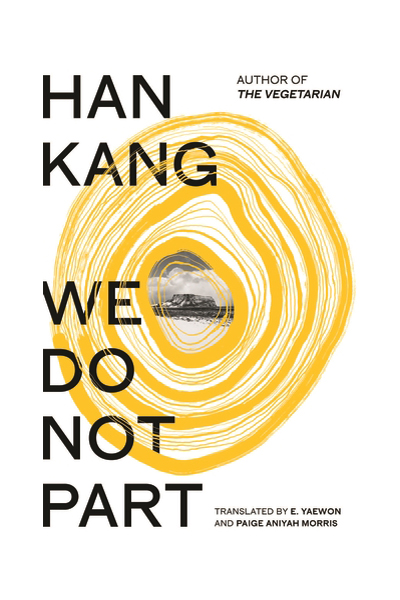

We Do Not Part

Han’s latest work, delving into South Korea’s painful history.

‘One morning in December, Kyungha is called to her friend Inseon’s hospital bedside. Airlifted to Seoul for an operation following a wood-chopping accident, Inseon is bedridden and begs Kyungha to take the first plane to her home on Jeju Island to feed her pet bird, who will quickly die unless it receives food.

‘Unfortunately, as Kyungha arrives a snowstorm hits. Lost in a world of snow, she begins to wonder if she will arrive in time to save the bird – or even survive the terrible cold that envelops her with every step. But she doesn’t yet suspect the darkness which awaits her at her friend’s house.

‘There, the long-buried story of Inseon’s family surges into light, in dreams and memories passed from mother to daughter, and in a painstakingly assembled archive, documenting the terrible massacre seventy years before that saw 30,000 Jeju civilians murdered.’

Published 20 February 2025

Hardback, £18.99, Penguin Books

Who Has Won The Nobel Prize In Literature?

Han Kang won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature. She joins 120 writers who have been awarded the prize since 1901. They are:

- 2023: Jon Fosse (Norwegian)

- 2022: Annie Ernaux (French)

- 2021: Abdulrazak Gurnah (Tanzanian)

- 2020: Louise Glück (American)

- 2019: Peter Handke (Austrian)

- 2018: Olga Tokarczuk (Polish)

- 2017: Kazuo Ishiguro (British)

- 2016: Bob Dylan (American)

- 2015: Svetlana Alexievich (Belarusian)

- 2014: Patrick Modiano (French)

- 2013: Alice Munro (Canadian)

- 2012: Mo Yan (Chinese)

- 2011: Tomas Tranströmer (Swedish)

- 2010: Mario Vargas Llosa (Peruvian/Spanish)

- 2009: Herta Müller (German-Romanian)

- 2008: J. M. G. Le Clézio (French/Mauritian)

- 2007: Doris Lessing (British)

- 2006: Orhan Pamuk (Turkish)

- 2005: Harold Pinter (British)

- 2004: Elfriede Jelinek (Austrian)

- 2003: J. M. Coetzee (South African/Australian)

- 2002: Imre Kertész (Hungarian)

- 2001: V. S. Naipaul (British/Trinidadian)

- 2000: Gao Xingjian (Chinese/French)

- 1999: Günter Grass (German)

- 1998: José Saramago (Portuguese)

- 1997: Dario Fo (Italian)

- 1996: Wisława Szymborska (Polish)

- 1995: Seamus Heaney (Irish)

- 1994: Kenzaburō Ōe (Japanese)

- 1993: Toni Morrison (American)

- 1992: Derek Walcott (Saint Lucian)

- 1991: Nadine Gordimer (South African)

- 1990: Octavio Paz (Mexican)

- 1989: Camilo José Cela (Spanish)

- 1988: Naguib Mahfouz (Egyptian)

- 1987: Joseph Brodsky (Russian-American)

- 1986: Wole Soyinka (Nigerian)

- 1985: Claude Simon (French)

- 1984: Jaroslav Seifert (Czech)

- 1983: William Golding (British)

- 1982: Gabriel García Márquez (Colombian)

- 1981: Elias Canetti (Bulgarian-British)

- 1980: Czesław Miłosz (Polish)

- 1979: Odysseas Elytis (Greek)

- 1978: Isaac Bashevis Singer (Polish-American)

- 1977: Vicente Aleixandre (Spanish)

- 1976: Saul Bellow (Canadian-American)

- 1975: Eugenio Montale (Italian)

- 1974: Eyvind Johnson (Swedish) and Harry Martinson (Swedish)

- 1973: Patrick White (Australian)

- 1972: Heinrich Böll (German)

- 1971: Pablo Neruda (Chilean)

- 1970: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (Russian)

- 1969: Samuel Beckett (Irish)

- 1968: Yasunari Kawabata (Japanese)

- 1967: Miguel Ángel Asturias (Guatemalan)

- 1966: Shmuel Yosef Agnon (Israeli) and Nelly Sachs (Swedish)

- 1965: Mikhail Sholokhov (Russian)

- 1964: Jean-Paul Sartre (French) [Refused the prize]

- 1963: Giorgos Seferis (Greek)

- 1962: John Steinbeck (American)

- 1961: Ivo Andrić (Yugoslavian)

- 1960: Saint-John Perse (French)

- 1959: Salvatore Quasimodo (Italian)

- 1958: Boris Pasternak (Russian) [Forced to decline]

- 1957: Albert Camus (French)

- 1956: Juan Ramón Jiménez (Spanish)

- 1955: Halldór Laxness (Icelandic)

- 1954: Ernest Hemingway (American)

- 1953: Winston Churchill (British)

- 1952: François Mauriac (French)

- 1951: Pär Lagerkvist (Swedish)

- 1950: Bertrand Russell (British)

- 1949: William Faulkner (American)

- 1948: T. S. Eliot (British)

- 1947: André Gide (French)

- 1946: Hermann Hesse (German-Swiss)

- 1945: Gabriela Mistral (Chilean)

- 1944: Johannes Vilhelm Jensen (Danish)

- 1940–43: No award given (World War II)

- 1939: Frans Eemil Sillanpää (Finnish)

- 1938: Pearl S. Buck (American)

- 1937: Roger Martin du Gard (French)

- 1936: Eugene O’Neill (American)

- 1935: No award given

- 1934: Luigi Pirandello (Italian)

- 1933: Ivan Bunin (Russian)

- 1932: John Galsworthy (British)

- 1931: Erik Axel Karlfeldt (Swedish, awarded posthumously)

- 1930: Sinclair Lewis (American)

- 1929: Thomas Mann (German)

- 1928: Sigrid Undset (Norwegian)

- 1927: Henri Bergson (French)

- 1926: Grazia Deledda (Italian)

- 1925: George Bernard Shaw (Irish)

- 1924: Władysław Reymont (Polish)

- 1923: William Butler Yeats (Irish)

- 1922: Jacinto Benavente (Spanish)

- 1921: Anatole France (French)

- 1920: Knut Hamsun (Norwegian)

- 1919: Carl Spitteler (Swiss)

- 1918: No award given (World War I)

- 1917: Karl Adolph Gjellerup (Danish) and Henrik Pontoppidan (Danish)

- 1916: Verner von Heidenstam (Swedish)

- 1915: Romain Rolland (French)

- 1914: No award given (World War I)

- 1913: Rabindranath Tagore (Indian)

- 1912: Gerhart Hauptmann (German)

- 1911: Maurice Maeterlinck (Belgian)

- 1910: Paul von Heyse (German)

- 1909: Selma Lagerlöf (Swedish)

- 1908: Rudolf Christoph Eucken (German)

- 1907: Rudyard Kipling (British)

- 1906: Giosuè Carducci (Italian)

- 1905: Henryk Sienkiewicz (Polish)

- 1904: Frédéric Mistral (French) and José Echegaray (Spanish)

- 1903: Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson (Norwegian)

- 1902: Theodor Mommsen (German)

- 1901: Sully Prudhomme (French)