Jane Goodall On Saving The Planet At 90

By

5 months ago

We meet the legendary conservationist

In 1960, Jane Goodall left her home in England to research chimpanzees in Tanzania. Today, at 90, her passion for saving them – and the planet – is as strong as ever. Lisa Grainger meets the world-leading ethologist and conservationist.

Exclusive Interview With Jane Goodall

If you haven’t seen the YouTube footage of Dr Jane Goodall being greeted by orphan chimpanzee Wounda in the Republic of Congo, then please treat yourself to a viewing.

Not only is it incredibly moving to see this slight, gentle, white-haired woman being looked at adoringly like a long-lost friend by a great ape, even though they had not previously met, but it also makes you realise that the chimp is only doing what so many of us would like to do – to give this extraordinary 90-year-old environmentalist a big fat hug.

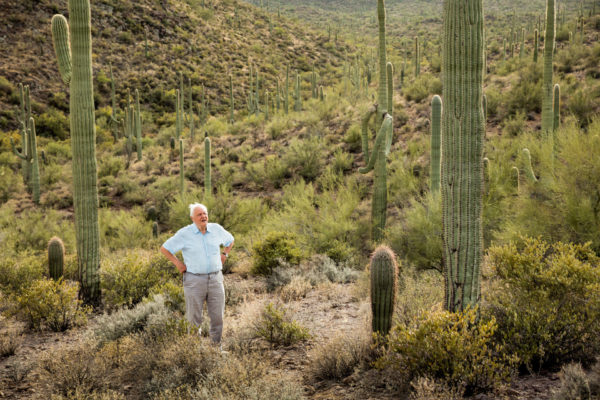

Across the world, few other nonagenarians, other than perhaps Sir David Attenborough, are quite as loved as Goodall. In the US, she is such a legend that she was name-checked in The Simpsons and was the woman that Michael Jackson said had inspired him to write Heal the World. In the UK, she’s been made a dame of the British Empire and UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan named her a messenger of peace. And every day, messages flood in for her from around the world – from her 2.4million followers on Facebook and 1.4 million on Instagram, ranging from children in Africa telling her about the vegetable gardens they’ve grown, and environmentalists in South America who have dedicated forests to her, to Inuit communities who want to consult her on climate change.

When I meet her for tea at her assistant’s flat in west London, I notice how reluctant she is to talk about her achievements. In person she is incredibly modest, sometimes even slightly shy. ‘I’ve come to realise that the only way to get to humans is to reach out to their hearts,’ the Cambridge-educated environmentalist says quietly, looking down thoughtfully at the elegant hands that have rescued so many chimpanzees. ‘Only if we understand from the heart will we care – and will help. And only if we help can this world be saved.’

Saving Chimpanzees

Goodall frequently speaks on the themes of hope and love: two of her books are titled With Love and The Book of Hope. But her understanding of the natural world is deeply rooted in science – in particular, the chimpanzees research in Tanzania she started for the palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey in 1960. It is the decimation of these animals about which she is most vocal. ‘A century ago, there were thought to be about two million chimps across 25 African countries,’ she says. ‘Now there are 340,000, if that. And in three of those 25 countries, there are no chimps left at all.’

One of the key reasons for their rapid decline, she says, is the bushmeat trade: the hunting of wild animals in the forest for food. Once, hunting for wild meat was done sustainably by local people for food. Now, thanks to industrialised logging throughout Africa – for wood that goes to America, Europe and Asia – roads have been cut deep into the forests, making it far easier for hunters to truck the meat out. Some research, she says, shows that about a million metric tonnes of bushmeat is being removed from the Congo Basin forests each year, resulting, in some areas, in ‘empty forest syndrome’, where no species are left at all. ‘The hunters go into an area and kill everything they find,’ Goodall says quietly. ‘Antelope, bushpigs, porcupines, birds and, of course, primates.’

Such mass slaughter of wild creatures is grim – but for her, the killing of chimpanzees is particularly horrifying. ‘Eating chimpanzees is, of course, wrong, partly because they’re so close to us – only about one percent of their DNA is different to ours. They have emotions. They make family bonds. And when you know them as I know them, as personalities, to eat one would be like eating another person, like cannibalism.’

While governments around the world know that to kill endangered animals is illegal (as she says, ‘It’s illegal to kill a chimpanzee; it’s illegal to catch one; it’s illegal to keep one’), preventing the undercover trade, she says, is extremely difficult and law enforcement ‘depends on who is in government in that country at the time’. And while it is also illegal to keep apes as pets in many parts of the world – including the UK and most states in the US – in the Middle East and China, she says, there is still a demand for them for private zoos. ‘What people don’t seem to understand is chimpanzees are not pets,’ she says passionately. ‘They are wild. They are sociable. They have family units, to which they’re attached. But still, these creatures are being flown out of countries and often in diplomatic bags, which means there is nothing anyone can do. It’s like the ivory trade. Except these are live animals, which have been torn from their families.’

Then often, when the adult chimpanzees turn aggressive and become too difficult to keep as pets, their owners dump them. In her Tchimpounga Sanctuary in the Republic of Congo – one of two Goodall Institute refuges for rescued apes across Africa – she has seen particularly heartbreaking sights. ‘Some animals brought to us are in a terrible condition: bald, ill, depressed,’ she says, shaking her head sadly. ‘In other places, they have been loved by their owners but were not treated as wild animals. One chimp had been owned by a Middle Eastern princess and arrived with four suitcases of clothes. Four suitcases! What sort of life had this animal had? Another chimp was brought to a sanctuary by an owner who loved him very much but had shaved him totally and put aftershave on him and a suit. The big problem in cases like this, is that these chimps can never be released into the wild again.’

Many that are released have only a small chance of survival – thanks to hunters, the territorial behaviour of other chimps and the encroachment of man into previously wild areas. ‘When I arrived in Gombe, western Tanzania, almost 65 years ago, and spent 19 years studying wild chimpanzees, there were forests all around. It was completely cut off. Now, the national park is surrounded by cultivated fields.’

It was this encroachment, she says, and the almost overnight disappearance of nearby forests, that made her realise that unless populations valued wildlife and learned to be conservationists themselves, the chimps were doomed. ‘There is absolutely no point in protecting chimps if we are not raising new generations to be better stewards,’ she says passionately. ‘What we need is a new generation who will look after the world.’

Which is why, having set up the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977 to protect chimpanzees, she established the Lake Tanganyika Forest and Education Project (Tacare) in 1994, to empower communities in the Kigoma area with community-led conservation programmes. In 1991, Jane began her global environmental and humanitarian programme Jane Goodall’s Roots & Shoots, which seeks to empower young people to become involved in hands-on projects of their choosing. It is now active in more than 70 countries.

It’s visiting these youth projects and meeting the students involved that has really given her hope, she says, her eyes suddenly sparkling. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, she visited a group of children in a refugee camp who’d learned how to grow vegetables and created the only green patch in the camp. There was also a boy who’d learned how to farm chickens, persuading more than 70 former hunters to keep and sell poultry, rather than to hunt. ‘I even got a letter from a Bronx boy who said that, because of what we’d learned, he’d written to Kellogg’s, complaining that chimpanzees shouldn’t be dressed in clothes on its cereal packets. And Kellogg’s wrote back telling him that it’d now stopped that packaging, as a result. So he realised that he could make difference. And that’s what it’s all about. Making people care and then helping them to do something about it.’

Forests are something about which the conservationist really cares. It was in the forests of Gombe in Tanzania that she made the celebrated finding that chimpanzees, like man, use tools. It was also there that she met her first husband, the wildlife photographer Baron Hugo van Lawick, with whom she had a son, and then her second husband, Derek Bryceson, who was the head of Tanzania’s National Parks.

She only left the forest, reluctantly, when in 1986 she realised that across Africa chimpanzees were vanishing – and that to save them, she must become an activist. From that day on, she says, her home became ‘everywhere… everywhere where I could meet other inspirational people who are as passionate as I am to try and save what we can. To make every individual realise that they matter and have a role to play. Every individual can make a difference.’

Spreading The Word

At the age of 90, her mission has broadened from the plight of chimpanzees to the demise of our planet. Today, she gives talks to packed audiences around the globe, to fundraise and to raise awareness on topics such as how to eat ethically (she is vegan), why we should boycott environmentally unethical companies and what to do about the melting icecaps.

Although she is unmistakeably British – in her modest dress, her clipped accent, her no-nonsense attitudes – her reach is worldwide. In her late eighties, she launched a podcast that was downloaded by more than 400,000 people in 130 countries, featuring guests from the author Margaret Atwood to the foreign correspondent John Simpson (who admitted he was once so besotted with Goodall, he used to carry with him a Sunday Times Magazine feature about her).

As I write, she’s on tour in Australia, then New Zealand, speaking in stadiums usually reserved for pop stars (if you want to track her on social media, use #wheresjane).

She is a woman on a mission. And, given the state of our planet and the urgency of the work that needs to be done, there is little hope of her retiring, she says, raising a slightly rueful eyebrow. ‘While I can still do something, I must. Besides, if I didn’t, I’d always want to return to Gombe. Under those trees is where I most feel at home.’

janegoodall.org.uk; rootsnshoots.org.uk