Tessa Hadley: Playfulness Is Vital To Storytelling

By

5 months ago

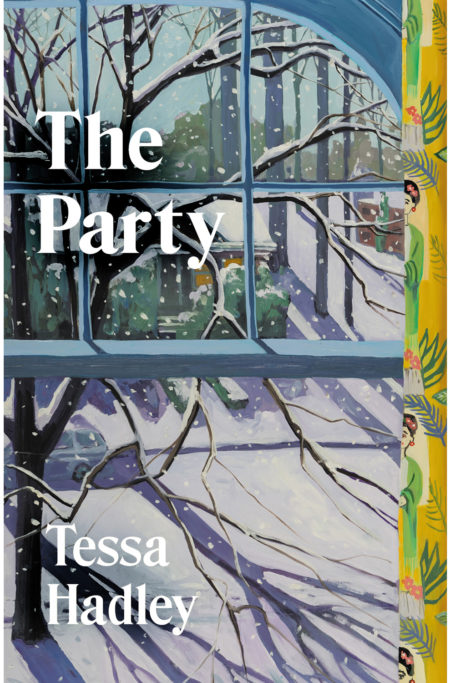

The Party is C&TH's book of the month

In November’s Book Club Tessa Hadley, one of our most relatable writers of women, talks to Belinda Bamber about the influence of D. H. Lawrence and Henry James on her work, and how playfulness is vital to storytelling.

C&TH Book Club: The Party by Tessa Hadley

Belinda Bamber: You are acclaimed for writing about ‘ordinary’ people’s lives: their loves, hopes, fears, betrayals, griefs, fear of mortality. Is that your focus?

Tessa Hadley: I’m not sure there really are any ordinary people. When I think back to the first time I wrote something which felt alive, it was when I understood that I could find my stories in the life heaped up all around me. I had thought no one would be interested, because these stories were too ordinary and familiar. Yet chat to anyone casually at a bus stop or on a train or at the school gate, and you quickly discover how extravagantly brave, crazy, desperate, insightful, horrible or funny people are. And the things that happen to them! What happens to people inside their lives is extraordinary. A character in my novel Clever Girl reflects that ‘the substantial outward things that happen to people were more mysterious really than all the invisible turmoil of the inner life’, and I do sometimes think that. The inner life is fascinating, but the huge events that turn life out of its path, away from our plans… The interest of people’s stories, and what happens next, never runs out.

BB: The women in your stories are often deliciously unpredictable, capricious and chaotic. Yet even though most of them, like Moira and Evelyn in The Party, are intent on gaining the attention of men, it’s the inter-female relationships (whether as friends, rivals, siblings or mother-daughter), that are the most intensely engaging. Why is this?

TH: You’re so right. It’s one of the things you see clearly, I think, as you grow older: that in the years when so many girls are obsessed with men and desperate for them, those men are often just an idea, a dream, and all the intricate, interesting real work of relationship and discovery is going on between the girls. (That whole scenario is reversible, although inflected very differently, if young men are obsessing about women.) This isn’t the whole story: when finally something real happens between a man and a woman then it can have all the momentousness of a collision of different worlds – an encounter between enemies, almost, sometimes. That strangeness and hostility give the male-female collision shock and friction, which is good to write. And I’m more and more interested in writing men, as I dare to do it more. The Party is very much a girls’ story, though. All the complexity of character and relationship is there between the two sisters. I’ve always loved writing sisters. I wonder if it’s because I don’t have one of my own? I have a lovely brother but that’s a quite different story.

BB: Your stories are rich with insight and understanding of human complexity. Which authors have taught you about life?

TH: I can’t easily separate what I know about life from experience, and what I know from reading. The two have been tangled together since I was a small child and fantasised belonging to the Swallows and Amazons, or being a Victorian orphan. At all important junctures of my life I made decisions at least partly based on the thinking of the writers I loved. Because D H Lawrence’s Ursula, in The Rainbow, saw through the false priests of higher education, I did too; I gave up my studies after my undergraduate degree, and had a baby instead. It was quite rash actually to live your life according to Lawrence. But on the other hand I don’t regret it. I’d rather have his passionate wrongness than too much dry irony or disenchantment.

BB: You completed a doctorate on the work of Henry James. How has his writing influenced you?

TH: That doctorate came later, in my early forties, when the babies were older and I’d rowed back slightly from trying to be Lawrentian. In fact I couldn’t read Lawrence for years, and it’s only recently I’ve been rediscovering how stunning his best work is. As for James: of course he’s passionate too, and although he’s ironic, that’s never his last word. I think James’s writing gives us permission to make big stories out of small things. His people have such grandeur: he writes about a privileged class, but that’s almost a metaphor for how much momentousness he attributes to their small stories. It’s easy to miss the fact that The Golden Bowl is just about a twisted love affair between four individuals. You have to find your distance, though, from the old masters’ style. It would be impossible to write now and sound anything like Henry James; or for that matter to sound anything like Lawrence. Each new era of writing exacts its own new tone, its own mood and language-world. But the great writers liberate us to try to be as bold and compendious and humane as they are.

BB: Many of your heroines struggle to balance the demands of motherhood and their artistic vocation. How did you manage to write while bringing up a family and do you think it’s got any easier for women?

TH: You might say it was easier to find time to write before most women went out to work. My first, failed, novels, the ones that never got published – thank goodness – were all written in the long hours when the children were at school. It’s never been all that difficult for bourgeois women of leisure to write novels. I think that the real difficulties have run deeper: in a culture that tended to attribute a lesser seriousness to women’s stories, women’s subject matter, the so-called domestic. In a hierarchy of literary power, the important male writers could seem somehow weightier, their wisdom sexier and more awe-inspiring. Some of these patterns are burned deep into our cultural heritage, our collective unconscious: women readers are at least as susceptible to the patterns as male readers, and it may take more than a generation to unlearn them. And also we need all kinds of writing. We want weighty arrogant ferocious writing too, we don’t want everything to be domesticated and sensitive and nice.

BB: Do your family and friends worry that you’ll use them as source material? (Is it impossible not to?)

TH: I’m very careful. As far as I know I’ve never upset anyone. I used one of my stepson’s stories once, where he fell over in the shower and pulled the shower curtain and rail down with him: he mentions that sometimes, but I think he finds it funny. My brother thinks I put him into my books as a sort of feral child, in contrast always with a much cleverer sister: he says I make him good-looking and sporting and physical and virtually inarticulate (he’s an art historian now). I deny this. Of course you’re borrowing from life ceaselessly, but if you love your family and friends it’s best to cover your tracks. (You see: niceness again.)

BB: One of the many relatable aspects of your heroines is the power they invest in clothes – Doll in The Party appears invincible to Moira and Evelyn because of her effortless Parisian chic. Do you enjoy dressing up for a party and what’s your favourite outfit for lifting your spirits?

TH: I love writing about how much is coded and communicated in the clothes women wear. My mother was a dressmaker and she always looked wonderful and had a gift for putting outfits together, even in her nineties. Dressing up is a performance of yourself in the world. I’ve never been as good at it as Doll, or as my mother; but one of the compensations for the end of youth is that you get better at dressing as yourself, instead of trying on costumes to perform as someone else. Sometimes putting on something good to go out feels like strapping on armour. Sometimes in the wrong clothes you feel undefended, as Evelyn does in the third chapter of The Party, when she knows that her hair needs washing, and fears that she looks overdressed in the things her sister has chosen for her.

BB: As a teacher of creative writing, do you think we’re ever too old (or too young) to seek publication?

One of the nice things about the novel form is that I think you really are better suited to it when you’re a bit older. I know that until I was in my forties I was just at sea in life, afloat in it but not able to authoritatively grasp it or describe it. I could only try to write other people’s books.

BB: Was your own early struggle to be published in any way helpful?

TH: Learning how to write doesn’t feel in retrospect like a slow gradual ascent to competence; it feels more like getting it wrong for a long time and then all of a sudden knowing better what to do, what to write about and how to position myself inside the words. So I don’t know whether I needed to go through the slog of failure for all those years, before I wrote anything worth reading. Perhaps. These processes are opaque. Who knows?

BB: In addition to The Party, you’ve published eight novels and four short collections. Has anything about the writing process got easier? Are you feeling excited about the next one?

TH: I’m actually in the middle of a novel; I broke off to write The Party and now I’m back inside it again. I’m always excited about writing and always full of trepidation in case it’s the wrong thing, in case it isn’t going to work. The sentence-by-sentence work doesn’t really get easier: but perhaps one writes from a basis of more confidence, belief that something’s possible. Also, I think I’m more ambitious, I’ve widened the scope of what I dare to try.

BB: You were born in Bristol, taught at Bath Spa University for many years, and your stories are usually rooted in the South West. If you had the chance to move to a different geographical location for a while, where would you choose (and would that affect your writing)?

TH: The geography of writing is fundamental. I find Bristol a very useful city to write about – big enough to do what you want with it in freedom, full of contrasts, spectacular to look at and a secret and dark history, all that architectural beauty paid for out of the profits from slavery. Mostly I set my Bristol writing in the recent past, more or less when I knew it well – it’s changed hugely since those days. For ten years I lived in London and again, it’s deliciously easy to set things there: anything works in that vast place, anything’s possible. The funny thing is that I’ve lived in Cardiff for most of my adult life but I find it more tricky to write about, although I’m doing it more these days. The difficulty is not because I don’t love it, but because even after all this time I don’t feel quite competent in what’s particular about living in Wales. I know it but I can’t voice it. There’s so much to learn about a place before you’re competent to do it justice. I wouldn’t want to move somewhere entirely new, not now. I’d feel too uprooted and inarticulate in my writing, I think.

BB: Why are many of your novels set in the mid-twentieth century?

TH: The answer’s probably quite simple, in that I mostly write about my lifetime. The Party is exceptional, in being set post-war, in the years just before I was born. But my mother talked to me so much about that time that I felt I knew it, and could risk it. I don’t know how those writers do it, who set their work in the distant past; although when it’s done really well, of course, historical fiction is a joy. But how do they find a language to recreate the otherness of those times? My writing comes out of testing each sentence against some perceived reality: have I done if justice? Are those the right words, is it true? But how could you check your fantasy of eighteenth-century England, say, against anything real? Quite a few of my novels are set in the twenty-first century, but as time passes and I grow older, of course I’m wary of that too! Am I too ignorant of what it’s like to be young now?

BB: If a long-lost relative bequeathed you a sizeable fund to make an intervention in the arts, what would you do with it?

TH: I would endow libraries up and down the land. There are two shuttered libraries near where we live in Cardiff, beautiful buildings both of them, which were open and thriving only a few years ago. They used to be full of teenagers doing their homework, older readers borrowing large print books, mothers with children, young people who might have been refugees, searching on the internet. They were full of books, and people using and reading and borrowing books. The closing of a library is like a death, or a light going out.

BB: You write powerfully and non-judgmentally about female sexual desire – ‘the sense of want in her like a tiger, a great rapacious cat’. Which, for you, is the greatest erotic novel ever written?

TH: I think in all the great novels there’s eros. Stories cluster around those places in life where the life force wells up into dailyness, and disrupts rational control (you see, I am still a Lawrentian!). There doesn’t need to be anything explicit for a passage of imaginative fiction to be erotic. For example in Jane Austen’s Persuasion, when Anne is left alone with Captain Wentworth for the first time, her naughty little nephew climbs onto her back while she’s kneeling, and she’s can’t get him off, and then the Captain lifts him away without saying a word… And the release of tension! The intensification of awareness between them, her palpitating heart! All in the bodily moment and her sensations, not a word spoken, or even an exchange of glances. It’s incredibly erotic.

BB: There’s a Truth or Dare episode in The Party that reminded me of the wealth of imaginative games played by characters in your books. Did you have a playful childhood? And is homo ludens being made redundant by modern technology?

TH: I played incessantly in my childhood: hovering perhaps a little bit on the edge of the great collective childhood games in the playground, the skipping games, the chanting by rote, Please Jack May I Cross the Water? and so on. Truth, Dare, Kiss or Promise came later… And with a couple of friends I also played, at school and at home, what we called even at the time ‘imaginative games’. Some of them were one-offs but others were repeated over and over like a play in repertoire, or a soap opera: the execution of Mary Queen of Scots, the herd of wild horses (we took our hairbands off and tossed our hair like manes). Or we were three women living on an island, rowing to the mainland for provisions. I have no doubt that it’s out of that world of dreaming and playing that storytelling and fiction comes. And I refuse to be pessimistic about homo ludens. I believe in the strength of the imagination, which will always surge up and be better that any synthetic pleasures. In my generation everyone worried it would all be ruined by television. Young people will grow tired of the sops of technology, they’ll get through them and come out on the other side, where there’s freedom.

BB: Many of your books capture a transformative episode for your characters, so that the final page brings not the sense of an ending, but of a new chapter beginning. Would you say you’re generally an optimist, and if so what is it about humanity that gives you hope in the face of gruelling daily headlines?

TH: It all depends on where you stop the story, doesn’t it? Because although I deliberately end The Party on that openness to the future, what’s actually happened to the girls the night before isn’t exactly pretty (in the very last line, they’re stirring sugar into the bitter coffee). But they’re full of fierce young hope… Yet I’ve smuggled something else into the middle of the story too; in the heart of the middle chapter I leap forwards, taking liberties with the otherwise steady chronological progression of the narrative, to imagine both the sisters at the end of their long lives, which have no doubt been full of sweetness and bitterness mixed together. I imagine them as old ladies, hanging on and hanging on for dear life, and then… I’m not really an optimist. There’s too much cruelty in the world, and in people. But I’m not exactly a pessimist either. Pessimism is its own kind of smugness. Yes obviously the worst thing you could ever imagine in your nightmares has really already happened somewhere, it’s happening to someone now… Life is hard, it’s terrible, that’s no surprise. How can we live with this? But it’s what we’ve got: there’s nothing else. And so all the mysteries and beauties we intuit must also be locked inside it somewhere. Not as a goal, not at the end of a dogged chronological forward slog, or at the end of the march of history, but locked away inside individual moments, for hope and art and happiness to uncover.

BB: Do you have experience of writing screenplays and which of your books would you most like to adapt as a series or a movie?

TH: There are two possibilities unfolding, but neither of them is definite yet, and I don’t think about them too much because I know how volatile and uncertain that world of screen is. I wouldn’t have a clue how to set about writing a screenplay. It’s surely the opposite to the wonderful power-trip of writing a novel or story, where you are director, actor, designer, cinematographer – and also in charge of costume!

BB: This is our ‘Gratitude’ issue. It’s a word that’s become culturally laden – what does it mean to you?

TH: Like all the good words, it can wear thin through overuse: it can come to sound unctuous. But it’s a good word when it’s heartfelt: I suppose it describes a certain kind of healthy passivity, a conscious acceptance, a treasuring, a pause from wanting. I find myself thinking ‘this is peace’, just now, at the most ordinary moments. But it’s easy to see how that thought could slide across into complacency.

BB: How do you plan to spend Christmas and will you be cooking?

TH: We’ve developed a tradition of having Christmas in the country with my two younger sons and my elderly mother and aunt. Both my mother and my aunt died last year – this will be our second Christmas without them. At some point my sons won’t want to keep coming to their parents. Up to this point I’ve always cooked, I like it, always pork because my aunt wouldn’t eat anything that flew (why?), but also pigs in blankets, stuffing, gravy, sprouts with chestnuts, the whole thing. Homemade Christmas pudding and brandy butter. I make very good mince pies, with my grandmother’s recipe for flaky pastry. There’s a kind of glory in turning out a full roast dinner, once in a very long while. (Mostly we’re fairly vegetarian.) But at some point I will gratefully resign that role to one of my sons or daughters-in-law, and become the grandmother sitting beside the tree waiting to be fed, gin and tonic in hand.