Is British Music Really The Best In The World?

By

4 months ago

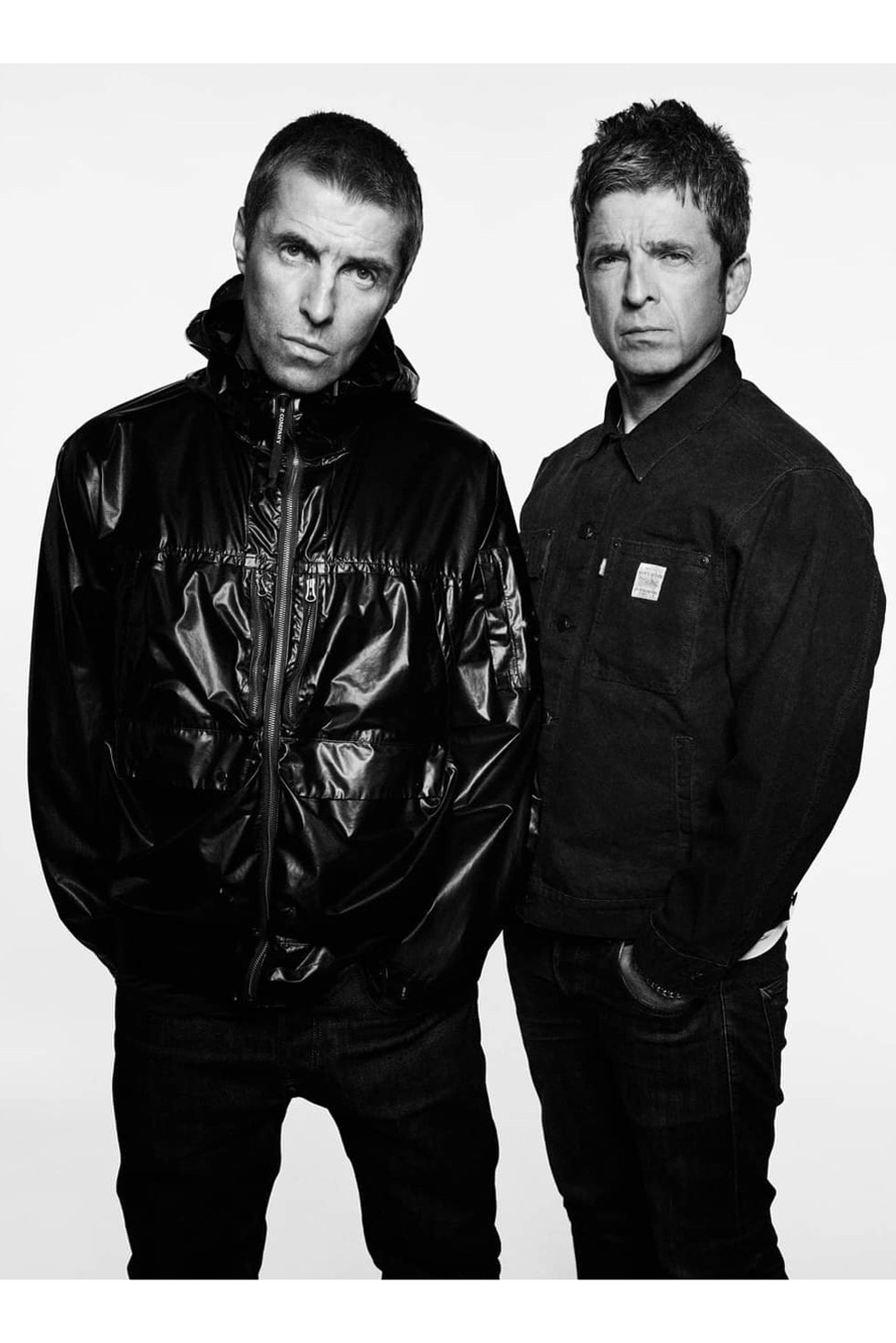

Behold the best of British

Music lover Dylan Jones reflecrs on why British music is the best in the world.

Here’s Why British Music Is So Popular

British music has always been the best in the world. Fact. End of. Move on. Elvis Presley may have gussied up the music industry in the mid-fifties – with some snake hips, a pair of pink pegs and a truck-driver’s hairdo – but he was a sensation rather than a musical force, an entertainer whose appeal was generational as much as anything. He helped America discover their hormones, inadvertently invented the generation gap, and influenced a swathe of copycat young singers.

But he wasn’t British. For a truly global sensation, we had to wait for The Beatles, a phenomenon whose IP seems only to increase each year. The regenerative aspect of British music has become such a fundamental part of our appeal that the UK is now as well known for its cultural intensity as its landscapes and political power. The world speaks English, and it sings English, and it has done for 60 years, when the Swinging Sixties were invented by four scallywags from Liverpool.

Each generation has its own sound, its own music, and mine was punk. London has been my home for my entire adult life, since I moved here from High Wycombe in the sticky summer of 1977, when I was just 17, during what was already being cynically talked about as the second iteration of Swinging London – the caveat being that this was the Summer of Hate rather than the Summer of Love.

In 1977 I was Dick Whittington, desperate to escape the grim orthodoxy of High Wycombe, and eager to throw myself into whatever was waiting for me just 50 miles away. I was leaving a Secondary Modern education for the bright lights of Chelsea – a foundation course at Chelsea School of Art – and I found it impossible to contain my excitement. London was not only the hotbed of punk, but it was also the crucible of everything I held dear: art, music, fashion… art school, transgression and music. And I wasn’t going to find much of that in High Wycombe. And seeing the likes of The Damned, The Jam and Generation X (I was stuck in the bar downstairs arguing with my girlfriend the night the Sex Pistols played) at the town’s infamous Nag’s Head pub (it shared a promoter with the 100 Club in Oxford Street), had only whetted my appetite.

So when I finally arrived, I honestly felt as though I was in a dream, even though culturally the city felt like it was exploding. For me, that summer was largely spent walking up and down the King’s Road looking like one of the Ramones, peering expectantly in shop windows and trying to keep out of fights.

London has always had the best music, and although Merseybeat kick-started the British revolution, everything and everyone – including The Beatles – soon moved to London. The capital was where it was at.

The next iteration of Swinging London was in the early-to-mid eighties, and specifically the year 1983. This wasn’t just the year of the famous Rolling Stone cover, celebrating the second British invasion, as the US charts were full of the likes of Duran Duran, Wham!, Spandau Ballet, Culture Club, Eurythmics and The Police; this was also the year that the British press started referring to the Eighties as the ‘Designer Decade’, the decade of style over content, of The Face, Blitz and i-D. Soon everyone would be talking about street style and the importance of designer fashion; Nick Logan, the editor of The Face, would turn up on Wogan, Levi’s would start making trendy TV cinema commercials for their jeans, and Katharine Hamnett would hijack a 1984 Downing Street reception by wearing a T-shirt proclaiming that ‘58% don’t want Pershing’, in reference to Margaret Thatcher’s decision to allow US Pershing missiles to be stationed in Britain.

The appeal of this new British pop was easy to grasp, and when I soon started travelling the world as a music journalist, I worked out quickly that the cultural equity of any writer for one of the glossy weeklies – Smash Hits, Number One or Record Mirror – was based solely on how well they knew the members of Duran Duran, Wham! or Spandau Ballet. At least among fans.

I remember being at a Hall and Oates concert in Cedar Rapids, in Iowa, and the mere fact that I worked for a glossy magazine in London – England! – coupled with the fact that I had not only just met but interviewed Duran Duran, meant that I was – fleetingly – almost as important as the Queen (at least to the twentysomething girls that night in the Five Seasons Center).

This was the golden period of British pop, when domestic stars could really do no wrong, as MTV transported them from the relative insignificance of London’s club scene to TV screens in bars, clubs and frat houses all over the US. For the big groups, this was the imperial zone, when British pop stars had a global media influence that far outweighed their domestic relevance. The likes of John Taylor, Martin Kemp and Andrew Ridgeley (the three pin-ups of the period) may have been famous in the UK, but in the rest of the world they were treated as genuinely international sex symbols.

The next time the world went mad for British pop was in the nineties, when Blur and Oasis knocked lumps out of each other, almost as media sport. It was fun, and it was genuine. As Tony Blair told me, some years later: ‘Cool Britannia represented fresh, more equal, getting rid of old attitudes and traditions that had no place in the modern world; a Britain that was young, vibrant and forward-looking and exciting.’ The extraordinary clamour for tickets to their reunion shows is an example of just how popular they remain. Which is what British music is at its very best.

These days, while we have temporarily allowed some Americans to bestride the global music world – stand up Taylor Swift, Drake, Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé, Ariana Grande, Billie Eilish, The Weeknd and Lady Gaga – we still have skin in the game. And what skin it is: Ed Sheeran, Coldplay, Adele, Elton John, Harry Styles, Raye, Arlo Parks, Dua Lipa, Little Simz and, of course, The Rolling Stones, still touring after half a century, still putting on the best show in town, and still showing our American cousins how to get their party started. As for me, I’m going back to my boxes of seven-inch singles, for one more blast of the Ramones, the Buzzcocks and The Clash.

Dylan Jones is Editor-at-Large of the Evening Standard and the author of a memoir, These Foolish Things.