Silliness Is The British Sauce

By

3 months ago

'Despair makes us smirk'

Hugo Rifkind explores the uniquely British knack for self-deprecating humour, delving into how this cultural trait is reflected in some of our most beloved popular culture.

What Underpins British Comedy? Silliness & Self-Deprecation

On every possible level, there has never been anything more British than Fawlty Towers, that seminal hotel sitcom of the 1970s. John Cleese, as Basil, is arrogant, chaotic, madcap, periodically pitiable, instinctively xenophobic, and forever teetering on the lip of disaster. And yet, he is mesmerising. Sometimes – just sometimes – he will say what everybody else thinks, but nobody will say, which he also knows he shouldn’t say, but does. Even physically, he also resembles the imposing, striding, world-conquering British officer class, but ratcheted up just a couple of notches too far. He is how the world sees us when they hate us, but also when they envy us, and we know it, and we also laugh louder than anybody else.

That, though, is just the top level. Dig deeper. On screen, Fawlty has a hot wife who hates him, in the shape of Prunella Scales’ Sybil, whose every garment resembles a negligee. And yet – so British, this – the real Cleese is also acting alongside his even hotter wife Connie Booth (Polly), who in the fiction hates him even more and is entirely out of his league. Contrast this with superhero fiction, a quintessentially American genre, and the way it is all about presenting people as bigger, better and far more powerful than they truly are. The British way is precisely the reverse.

For a slightly more recent example of the same thing, take Ricky Gervais’ workplace drama The Office, and all the things it had to jettison to be remade for America. Pessimism, despair and the impossibility of redemption. Cold days, whining air-conditioning and the slate grey skies above slate grey carparks. Get stuck in a room at a business hotel for a day with the US version’s Michael Scott (Steve Carell) and you’d eventually come to love him. Do the same with Gervais’ David Brent and you’d probably throttle yourself with the bed runner. The British way, though, is to be proud of that. Despair makes us smirk.

Consider Blackadder, and particularly the stark brilliance of that last series, in the First World War trenches. Rowan Atkinson’s shifty Captain, Hugh Laurie’s dim Lieutenant, Stephen Fry’s buffoon general. It’s a story of our greatest heroes in which there are no heroes, right up until the end, when they are all heroes. Or take the American Austin Powers, Mike Myers’ tremendous parody of both James Bond and Britishness itself, which I always adored, and yet which always seemed to miss the fact that Bond himself had made most of the jokes already.

Only in Britain would you find a beloved Queen hanging out with an equally beloved bear

Britishness undercuts itself. That’s the secret. For a whole generation of public figures, the greatest accolade that could be bestowed upon them was to be mocked on Spitting Image. Indeed, the mere injection of Britishness is enough, often, to make a story absurd. I once heard the novelist Toby Litt describe Douglas Adams’ peerless sci-fi comedy The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy as being about ‘the agony of being British in space’ and I have never quite got over it. Or, to go back to Cleese and his gang, consider Life Of Brian, which is simply and purely about how preposterous the gospels would be if the Messiah came from Maidstone.

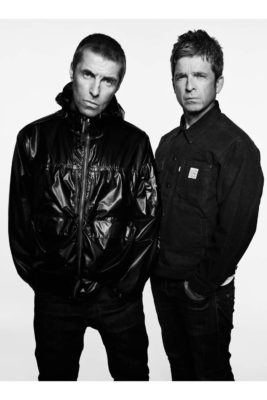

We do the same with music. People joke, still, about Ringo being the shit one from The Beatles, but they wouldn’t have been The Beatles without him. Imagine Bob Dylan or The Eagles coming up with Octopus’s Garden. People would think they’d lost their minds. Or contrast, say, the many reincarnations of Prince with those of David Bowie. The former, hopelessly sincere. The latter, always with a twinkle. Likewise, contrast the Pussycat Dolls with the Spice Girls; one forever oiled, flawless and panting, the other looking like they were on their way to the Boots staff Christmas party. Take Taylor Swift in concert, as polished between songs as she is during them. Then ponder our own Adele, who between swooning songs of heartbreak will cackle and cuss like a navvy.

Silliness is the magic British sauce. Other nations can be silly, too, of course, but for most it is a binary choice; take yourself seriously or don’t. Only we have that knack of weaponising our silliness, of using it to disarm our critics, freeing ourselves up to covertly grow serious before they’ve quite caught up. Ponder Strictly Come Dancing, and how po-faced it would be if not for Claudia Winkleman forever raising her eyebrows. This, despite the way you can’t even see her eyebrows, because of her fringe. Ponder the beloved amateurism of The Great British Bake Off. Or, if you missed one of the loveliest and most British TV shows of recent years, spend a few hours in front of The Detectorists, Mackenzie Crook’s tale of Essex treasure hunters. It’s a story of small, silly people, whose essential human nobility emerges not despite their mundanity, but entirely because of it.

By now it may seem like I’m listing articles of popular culture almost at random, but that’s the point; you see it everywhere. We have a culture in our national image. We have the most famous Parliament on the planet, yet inside it is crumbling, full of mice, and smells of boiled beef.

We also have the world’s most prominent royals, able to do all that Star Wars-level militaristic pageantry at the drop of a hat. Yet we also know the only reason the Queen liked having a yacht was that the rooms were small and poky, and people left her alone. We have, I think, not one royal – not even Prince Harry, or the Duke of York – who would not secretly be happiest up to their knees in mud on a hillside next to a dog. No wonder our late Queen hung out with Paddington Bear. She virtually was Paddington Bear. Imagine Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin with Paddington Bear. They’d look like they were about to have him killed.