5 Top Tips For Poetry Writing

By

3 years ago

Budding poets: here's where to begin

Not only is poetry writing a creative outlet, but it also offers therapeutic and wellbeing benefits of putting pen to paper. If you fancy giving it a go, but you’re not sure where to start, mentors from Write for Life, the longest-running refugee writing group in Britain, are here to help with their top tips.

And if you fancy submitting in a poetry competition, UK-based charity, Freedom From Torture is back with its competition and entries can be submitted online this week. It’ll be judged by eminent novelist and Booker Prize winner Alan Hollinghurst and editors of Ambit. The winning poem will be performed at the charity’s star-studded literary event on the 24 November alongside famed authors such as Julian Barnes and Elif Shafak.

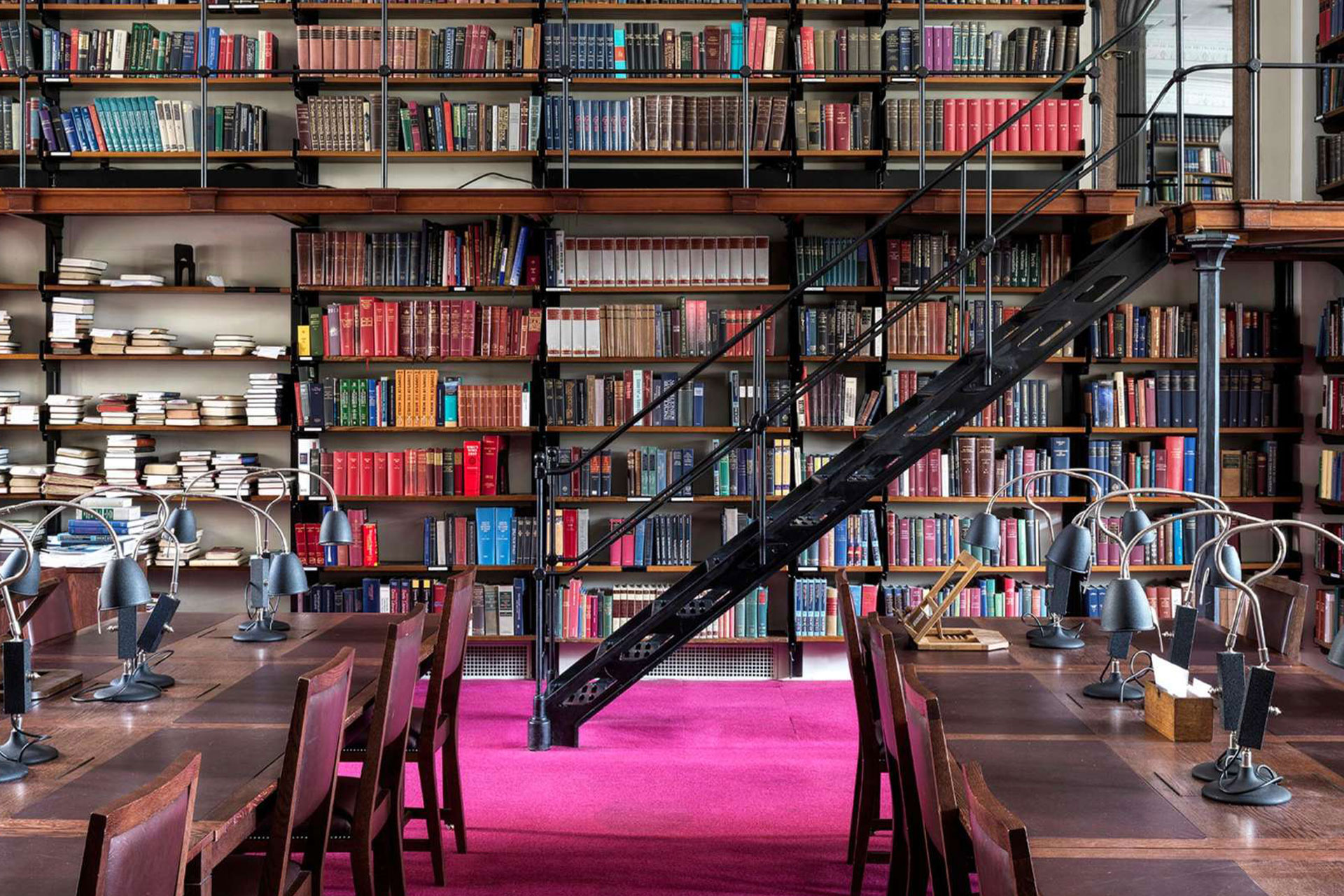

London Library

5 Top Tips For Poetry Writing

Tip 1: Starting off

For most people who write, these questions tend to pop up. You might ask: what images will I describe and what feelings do I want my reader to have? And before all that even: why do I want to write a poem? If you want to, you probably have something that really needs to get out. What is it? Be honest, be ready to fail, and be ready to be embarrassed. Most decisions to write a poem end in half a page of words that don’t go anywhere, so don’t be disheartened. People often worry they won’t ‘get it’. Carry on if you feel you don’t get it, you will eventually, if you want to. In any case, maybe no one really gets it completely. Like understanding the weather.

Tip 2: Forming your text

Poems don’t have much time to make their mark. Stanzas and lines that are there for introducing and easing in the reader can sometimes just dilute the punch. Arriving smack bang in the middle of a moment, a feeling or an event can bring us right to the middle without any run up. The same can be said for endings. It can be tempting to ‘tie a bow’ on the end of poems to say ‘now I’m finished’ or ‘in conclusion, here is my argument’ but leaving the reader without a ‘goodbye’ can make the poem feel more concentrated and powerful.

Tip 3: Pay careful attention to each line

Treat each line as if it’s its own poem. Give each line the attention and care of a whole poem. Are there any words that aren’t working hard enough? Is every single word adding something important to the line? What would the line look like without any excess? If the line was a scale, how much does each word weigh? Does the poem need a balanced line here? Or an unbalanced one? Are all the lines in the poem similarly balanced? Does there need to be more tension so that there can be a feeling of release?

Tip 4: Music and voice

Poetry was originally born from music and performance, just like the novel’s ancestor is spoken storytelling. Early poets were musicians so don’t forget this birth in music. What kind of music? If you listen to birdsong and other sounds in nature, they aren’t usually regular or melodic like chamber music or pop songs. What is called ‘musicality’ in poetry can come from rhythm, and rhyme, and just the way our natural human languages make us feel through the hundreds of sounds needed to speak them. It’s the same whether your words are profound, or ordinary, or even nonsense. So read your lines out loud. Read your poems out loud. Read your diary and your nonsense scribbles out loud and listen until you are struck by the way something sounds. You might find out how your voice sounds, and what it is trying to say.

Tip 5: Line endings vs line breaks

Every line must end – deciding where it ends can change everything from; the stresses within, the way rhymes fall, the key word that stands out from the line, rhythm, metre, and most importantly the line’s relationship with other lines. Whether a sentence is kept intact, and the line is allowed to carry on and finish naturally, a line is ended at a more natural pause in the syntax or ended in a way that cuts in a dislocating way is a choice for each line. There is no right or wrong answer or correct way to end a line but the way the lines end should service the needs of the poem. Is the poem frantic and in the style of flashing thoughts and ideas? Maybe breaking some of the syntax across multiple lines might make it read more like a messy internal thought process. Maybe having lines that end more naturally and have less tension with the syntax will feel more whole and cohesive or stative. It’s your choice.

Where?

A New Chapter – Freedom from Torture Poetry Competition

Online poetry competition via a-new-chapter-poetry-competition.raisely.com as part of FFT’s Literary Festival running for the month of November.

When?

Deadline to submit: Friday 28 October 2022 at 5pm

How?

The theme, A New Chapter, celebrates the hope, optimism and strength that it takes for refugees and asylum seekers building a new life in the UK, especially for those who have survived torture. It can mean many different things to different people, and the entry should represent what a new chapter means to you. Poems can be any length and style and must be the entrant’s original work. Entries must not have been published, self-published, broadcast or featured among the winners in any previous competition before.

Donate £5 (or more, if you wish) and complete your details and upload your poem via a-new-chapter-poetry-competition.raisely.com/poetrysubmission.

If you have lived experience as a refugee or asylum seeker, you can enter free of charge by sending your poem to [email protected] with the subject line ‘Poetry competition’.

The charity will be touch if you are selected as one of the winners.

- First prize: Perform your winning poem (live or pre-recorded) at the charity’s literary evening hosted by Alexei Sayle at the London Library on 24 November alongside authors Julian Barnes, Elif Shafak, Alan Hollinghurst and poet Inua Ellams. The winning poem will also be published in Ambit Magazine’s 250th issue in March 2023 along with a year’s supply of Papier personalised notebooks and a bundle of books from the Folio Society.

- Runners up with receive a bundle of books from the Folio Society. All winners will have their poem featured on Freedom from Torture’s website and social media.

- Funds raised will support FFT’s creative group projects for survivors such as art, music and the creative writing group Write to Life, the longest-running refugee writing group in Britain, and the only one specifically for survivors of torture.