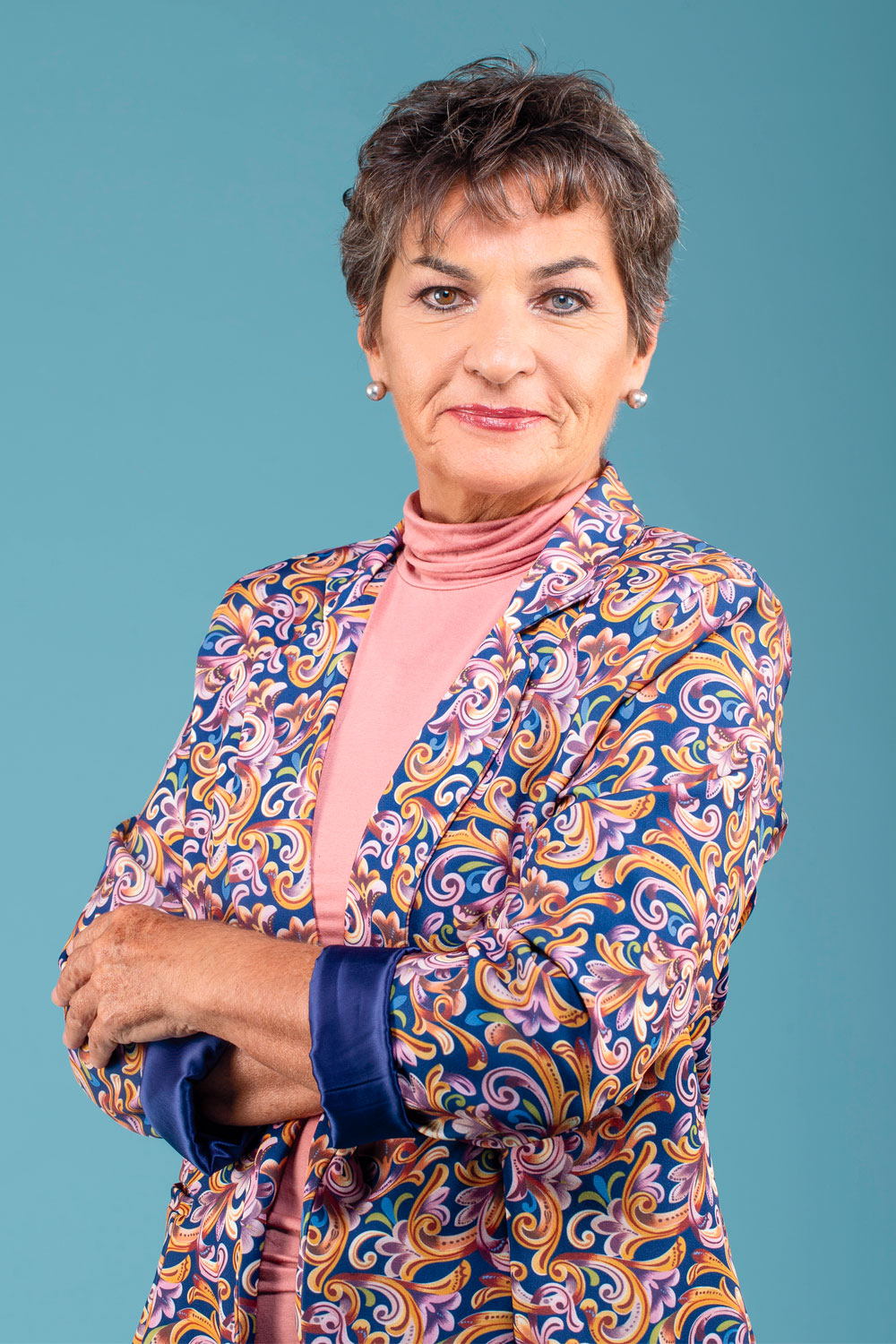

Christiana Figueres Lost Everything – And Then Led Paris Climate Talks

By

10 months ago

How her marriage ending may have led to the Paris Agreement

Christiana Figueres led the world in climate talks in 2015. As the Paris Agreement came together, her own world was falling apart. But, she says to Annabel Heseltine, the end of her 25-year marriage may have been the very thing that led to the success of those climate talks.

Christiana Figueres On Divorce, Meditation & The 2015 Paris Agreement

In 2015, Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres achieved a phenomenal world first; bringing together 196 countries to sign the Paris Agreement, a united global commitment to keep temperatures to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. But nearly ten years later, as COP succeeds COP and news reports flood in of climatic turbulence and species extinction, Figueres acknowledges the despair of leading climate scientists who believe that unless we radically change our living habits now we will crash through that ceiling, hitting global temperatures 2.5 to three degrees above pre-industrial levels. It’s a despair mirrored in communities across the world.

‘So many people today are in grief about what we are losing. I too am in a sense of deep loss about the impact on nature and on humanity,’ she says. But the question to ask is: ‘So what are we going to do about it?’ Are we going to sit and wallow in our despair? Absolutely not,’ says Figueres, who co-hosts the podcast series Outrage + Optimism. She’s calling for a quick energy transition but is also attuned to the grief felt by so many, not least because of her own personal experience.

As the Paris Agreement was adopted, her world was falling apart

At the time of the Paris negotiations, the executive secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was suffering from suicidal trauma. Her now-former husband’s revelation that their 25-year ‘happy’ marriage was a sham triggered a personal crisis. ‘Out of the clear blue sky, he told me he had never been loyal to me. It hit me so hard that I became suicidal.’ Figueres was working in Germany with a team of 500 people but had to stop travelling by train alone because her impulse was to throw herself in front of one. It became unbearable; she was crying herself to sleep every night, then getting up in the morning, putting on a smile and going to work.

As she talks, I cannot help wondering whether the apparent coincidence of what happened next was not in fact the serendipity of a cruel but effective divine intervention. ‘When things became completely unsustainable,’ she told me, ‘I was blessed by the forces of the universe.’ She met Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk widely considered to be the father of mindfulness in the West. Later, she credited his teachings with informing the language she used to secure the Paris Agreement, an extraordinary feat in bringing so many people with such diverse cultural and economic requirements to one table. ‘Nobody really comes to listen,’ she says, ‘but to inform everyone else of their position.’ (She conjures a mind-boggling maze; 196 countries, each with at least three different points of view on 70 different topics of negotiation, all of which had to be unravelled.)

Her own personal story unravelled over the Christmas break when Figueres sought out Thay (as his students called him, before he passed away in 2022) at Waldbröl, the site of a former mental institution only 45 minutes away from the negotiations. During WWII, all 700 of its patients were exterminated by the Nazis, who then used it to house its Nazi Youth. ‘Thay chose this place that had seen absolute, inhuman cruelty deliberately to show it was completely possible to turn pain into love, victim into victor, hate into love and forgiveness,’ said Figueres. ‘It was such a powerful story, mirroring the journey of the climate negotiations. A journey from blame to collaboration. From feeling paralysed and helpless to feeling empowered.’

Thay’s teachings enabled Christiana to shift away from thinking of herself as a victim

A key challenge in the climate negotiations was the rift between the global north and global south, with the latter feeling a victim of the industrialised countries of the northern hemisphere, says Figueres. ‘Objectively, the developing countries are justified in feeling a victim. But if you perceive yourself as such, implicitly you are accusing somebody else of being the perpetrator and that other person is never going to happily take on the mantle of perpetration. So it’s a seesaw of accusations.’

From Thay’s teachings Figueres understood the analogy in her personal life, recognising that if she perceived herself as a victim, she carried that dynamic too. So, she worked on changing her own mindset. ‘I had to understand that I have the tools to walk with a different energy. As does everyone.’ It was hard work but in the process of getting out of her own victimhood ‘my conversation changed and I saw a change within the conversations I was having.’

Figueres realised that rather than preaching to leaders, she was far more effective asking questions about their long-term interests, how they saw themselves growing as nations and how they could protect their people. ‘The more they talked, the more they moved into First World thinking and considered their responsibility in the future. Then we could find a common ground and have a different conversation.’

Figueres studied with Thay until his death, and continues to share his teachings and the insights gained from them with climate activists, leaders and people working with global diversity issues. ‘I am so grateful because if I had not been in that space of my own grief and despair, I probably would have intellectualised it and would not have fully identified with the pain and the grief that I see in so many of my fellow colleagues working on climate and biodiversity issues,’ she says. ‘Now it goes straight to my heart.’

Accepting her own trauma empowered Figueres to lead others with courage and conviction in a way that is refreshingly different from the traditional stiff-upper-lip masculine stereotype, who could never have conceived of admitting to suicidal tendencies while leading world negotiations. ‘It’s so important that we all recognise that we’re just human beings, all trying our very best at different points in our life, with different challenges.’ And the greatest challenge is climate change, says Figueres, the daughter of the former president of Costa Rica, a country leading by example in the fight to change the scary trajectory global warming is taking us towards; its electricity comes from renewables which now need to be rationed because of drought.

In a neat circle we return to talking about Nature’s gift as a healer and a teacher. Nature is fascinating, says Figueres who has just taken a biomimicry course with Janine Benyus, who believes that the more people learn from nature’s mentors, the more they’ll want to protect nature. ‘But what was most fascinating is the fact that we think nature is out there and that we are in here. The first thing we have to do is disarm this separation. We are in nature, not apart from, but a part of it. We are so busy with our humanness, that we don’t take the time to see what’s around us, hugging, embracing and feeding us. The more we understand that, the better we are able to embrace the opportunities staring us in the face.

‘Twenty or 30 years ago we thought all we had to do was take the pressure off nature and optimise our use of resources, but now because of our footprint we need to do more. We need to roll up our sleeves and get stuck in. And we can,’ says the indefatigable diplomat. ‘We have the technologies, the policies and the finance to do it. To be able to say that we were part of the regeneration is an incredible gift.’

The full interview with Christiana Figueres can be heard on Annabel’s podcast series Hope Springs, by the Resurgence Trust, launching on 13 September; resurgence.org