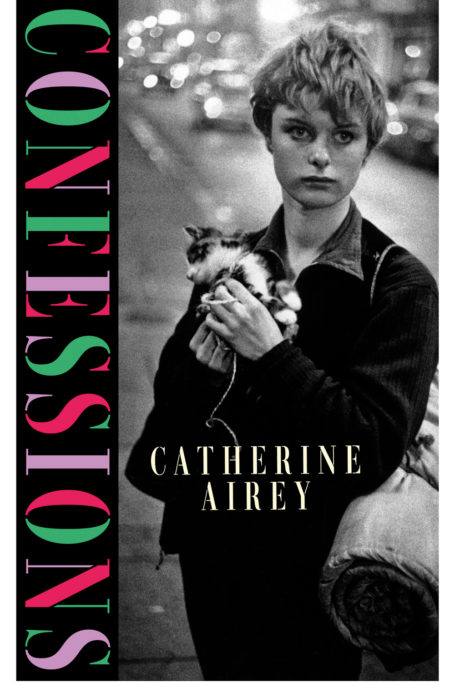

Catherine Airey On Break-Ups, New Beginnings & Her Debut Novel, Confessions

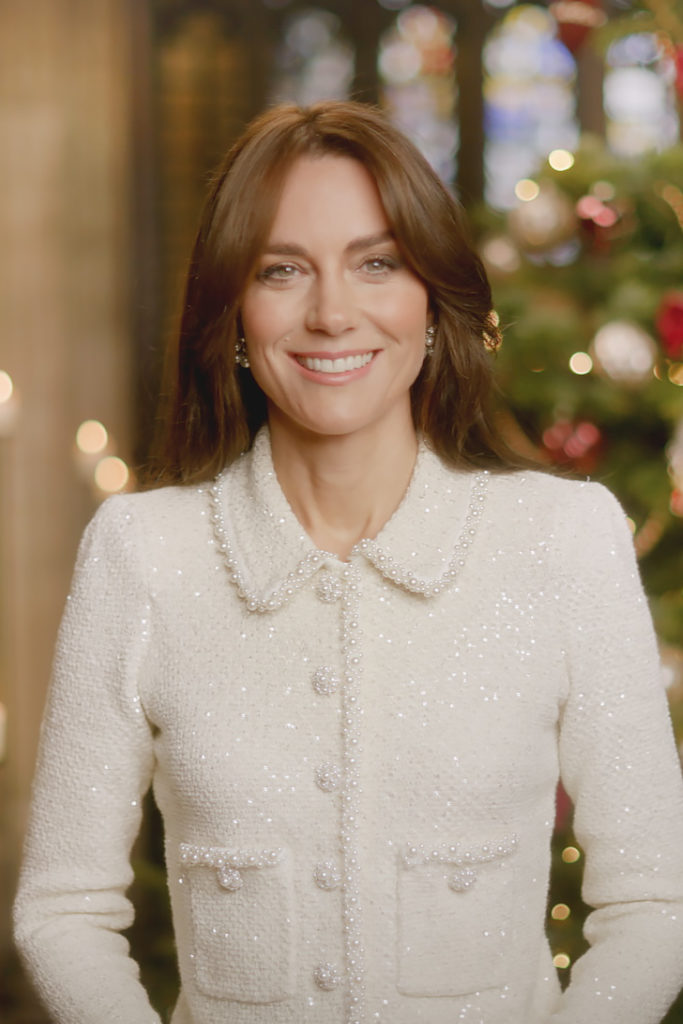

By

11 months ago

Confessions by Catherine Airey is the C&TH Book Club pick this month

In January’s Book Club, debut author Catherine Airey talks to Belinda Bamber about break-ups and new beginnings.

C&TH Book Club: Confessions by Catherine Airey

Belinda Bamber: Confessions begins with 16-year-old Cora dazedly wandering Manhattan on 9/11 and ends with her grown-up daughter Lyca in Ireland in 2023. You also revisit the 1970s to tell the stories of Cora’s mother, Maíre, and her aunt Róisín. What was the seed of this transatlantic narrative about three generations of Dooley women?

Catherine Airey: I started writing Confessions not long after I’d moved from London to rural Ireland. Not a crossing of the Atlantic, but a crossing to a different land. I was on my own, depending mostly on very kind strangers. This time was particularly tender for me since I’d just been through a break-up. I’d found out that a close friend of mine had got together with my ex, which was a big shock. I was thinking about the nature of these emotions – what it felt like to have lost both those people from my life. I wanted to talk to them both, very badly, every day. I wanted to know what they were doing, the conversations they were having (especially the ones that might have been about me). At the same time, I knew I needed to protect myself. This feeling fuelled the writing of Confessions and helped set up some of the relationship dynamics. But the more I wrote, the more I got distracted. As the rest of the book took shape, the love triangle element shrank. Probably a sign that my own heart was mending.

BB: The book opens vividly on the day the Twin Towers were hit – what made you decide on that dramatic opener?

CA: When 9/11 happened, I was only eight, so a good bit younger than Cora. It was the first big world disaster I was aware of. My mum told me about it in the car on the way home from school, and then I watched footage on TV. I remember being confused about the time difference, because it was still morning in New York. I was also trying to get my head around the height of the towers. The tallest building in my town had seven storeys. I’d counted the windows, and imagined working there when I was grown up. Comparing that to the height of the Twin Towers was disorientating, reframing my sense of the world. I think that’s something I carried with me as a writer – being interested in juxtapositions of scale, the minutiae of the everyday coming into contact with world-changing events.

I wrote about what had happened in my diary: ‘Two air plains went into the twin towers in America. It is so sad.’ This was the first time I’d documented something bigger than what was going on in my little life in suburban England. It felt like a beginning, a new awareness that bad things would happen, and that you couldn’t stop them from happening.

After that, I was always a bit obsessed with 9/11, watching the documentaries which came out every year. Everyone could remember where they were when they heard about it. So many people had a story about that day, even if they’d been nowhere near New York. It felt like a touchstone, a point for the reader to orientate themselves in the story. There’s now a whole generation of people who weren’t alive when 9/11 happened and I wanted to capture something about that time for those who might only have a big-picture understanding of it as a tragedy.

BB: How did you tackle such an intricate plot and bring everything together at the end like a jigsaw (which is a recurrent motif in the story)?

CA: It was hard! But only at points. Most of the time I was just writing without thinking about how the parts might fit together, partly because I’m not very organised, and also because the writing itself is where the ideas come from. For me at least, plot is something that reveals itself. What happens should be surprising, for the writer as well as the reader. But this approach can be overwhelming. Every now and then, I’d need to print bits out. I would think more overtly about plot and pacing then, cutting sections up with scissors and rearranging them on the floor (a bit like Róisín’s Scream School manuscript). So it was a kind of retroactive planning.

The jigsaw analogy is a good one. My mum went through a phase of doing difficult jigsaws when I was little. One of them was of the Titanic, 1,000 pieces. Printed on each piece of that puzzle was a photo of marine life. One thousand discreet photos that came together in a specific arrangement to reveal an overarching image. Writing a novel is a bit like that, but without being able to see the picture on the box.

BB: How did you transition from avid reader to debut writer?

CA: Reading for me has always been an escape. It calms anxiety precisely because you don’t have control over what’s coming next. When I’m reading, the words on the page replace the voice in my head, which is often uncertain, fearful. Even if the story is alarming or upsetting, there’s something comforting about the fact you can’t change the outcome. Novels are a safe way to experience the emotions of an experience, without it actually happening to you. I was always deeply envious, though, of novelists. What bravery, I thought, to make something up – and to not give up.

Reading and writing are really quite opposite activities, passive and active. At the same time, writing does require a kind of passivity, an openness. It’s not the same sort of bravery as being out in the world doing scary things. It requires sitting down with yourself, day after day, pushing aside the uncertainty and doubt. While I was writing the first draft of Confessions, I pretty much stopped reading novels, partly because they made me feel intimidated, but also because I had to let go of the security blanket of other people’s voices and trust my own instead. There’s a tentativeness to some of the narrators in Confessions that probably stems from this. Sometimes, having more choices only makes the uncertainty worse, like having too many options on a restaurant menu.

BB: If you could go back and change anything in your life, what would it be?

CA: It’s tempting to think in terms of right and wrong, like life is some kind of videogame. But I think I’ve realised you can’t live like that, regretting the past or wishing things were different. So many people, now and throughout history, have not been free to make their own choices. I try to be grateful for the freedom I have to define my own life.

BB: What inspired the generational theme?

CA: I grew up next door to my Irish grandmother, a foreboding, secretive woman. Completely fascinating to me. She was born mostly deaf in rural County Cork in 1921, yet became a doctor and moved to England on her own after WWII. She wasn’t one for talking, which made her even more mysterious. When I was 14, she was diagnosed with dementia (though there had been signs of it probably throughout my childhood). I never got to find out all the things I wish I knew about her now, but wondering about them has been a rich source for me as a writer. What was it like when she regained some of her hearing after an experimental surgery? How did she feel being one of the only girls studying medicine at University College Cork, while the war was raging through the rest of Europe? What did she notice about England and what did she miss about home? The stories I know of her have all been handed down by other people, then embellished in my imagination. I’m interested in this kind of inheritance: the maps we make of ourselves based on incomplete (and often inaccurate) stories of what came before.

BB: How have you broken away from family tradition?

CA: Most of the people in my family have careers in the sciences, but my dad is a big reader (my grandma was, too) so there were a lot of books in the house I grew up in. When I got into Cambridge to study English at university, I wrote down the news on a piece of paper for my grandma to read. She looked at the paper for a while, then said: ‘What on earth would you want to do that for?’ I found this very funny, even at the time. Now it makes me think about how odd people must have thought it was for her to become a doctor. They’re very different vocations, and arguably being a doctor is a lot more useful than writing novels, but I like that we both went against the grain. I got that from her.

BB: Catholicism and the idea of a Greater Plan are strong threads in Confessions – what’s your own religious background?

CA: Both my parents come from Catholic backgrounds. My dad would probably describe himself as an atheist. He was sent to Catholic boarding school, which ironically rid him of any faith in God. Because of this, my sisters and I went to Church of England schools, but then went with my mum to Mass on Sundays, which wasn’t something I admitted to my friends at school. Religion wasn’t a big part of daily life at home. We didn’t say prayers or talk about God, but I had my own secret religious rituals – long conversations with God in my head while I was in bed. I would pray for things I wanted and offer up promises in exchange. It was quite stressful, maintaining this relationship, balancing everything up. I kept it all completely secret.

I don’t believe in God now, but I’m still susceptible to Greater Plan thinking. It’s very seductive to believe things happen for a reason. Part of why Ireland feels so familiar to me is because it’s still very much a Catholic country. For generations, secrecy and shame were woven into the fabric of the culture. As an institution, the Catholic Church has caused a lot of harm to vulnerable people. But on a personal level, I’m quite grateful for my religious upbringing now. At the very least, it fostered a practice of putting thoughts into words, developing my own interiority.

BB: Despite the title, not every character narrates their own story. For example, Róisín seems to be narrating Maíre’s. Why?

CA: I wrote a lot of the 1970s Burtonport sections in the third person, detailing the lives of the different members of the Dooley family in Ireland. Originally, I thought these parts wouldn’t even feature in the novel; I was just working them out for myself as context. Eventually, though, I was able to find an angle for each narrator. These sections came alive as soon as I was able to see them through Róisín’s eyes, to have her be the sort of child who kept a diary. Her sister’s section that follows is different. Maíre isn’t a writer, so I wanted her voice to feel very distinct. Another reason why her part is written in the second person is that I wanted each part to exist almost like an artefact, like evidence. The novel as a whole is an acknowledgement that all stories are fiction. Every version of the truth is fallible and incomplete.

BB: I enjoyed Scream School and the way the Burtonport house became an almost Dickensian locus, complete with an attic full of letters and secrets. What inspired it?

CA: The house in Confessions is based on a real house in Burtonport, and a group known as the Screamers really did live there for a few years in the 1970s. This attracted quite a bit of media attention at the time, which I was drawn to in my research. I was more interested, though, in what the locals would have thought about this group turning up in the village, what kind of gossip would have started to circulate, and how that might have been projected onto the house itself.

Certain houses are particularly appealing to children, especially those they never get to go inside. The house’s exterior is the backdrop to Maíre and Róisín’s creative play, helping them develop their artistic skills. Later on, we see inside the house from Lyca’s perspective. She doesn’t see the house as mysterious in the way her school friends do because she’s lived there all her life. She has to see it through their eyes for it to come to life, so she can begin to search for its secrets.

The house I grew up in did provide some inspiration for Lyca’s sections in Confessions. It was the same house that my dad grew up in, so there was a lot of stuff in it that had been there for half a century. When I was a teenager and my grandma had to be moved to a nursing home, I helped my parents sort through some of her stuff. We found letters that my grandad had written to my grandma before they were married. She had gone back to Ireland to tell her family she was marrying a Protestant. Meanwhile, he was making visits to the local priest so he could convert to Catholicism. I loved stumbling across artefacts like this, which brought the past to life, then later filling in the gaps myself.

BB: Inspired by the Dooleys, I’ve started to play Alphabet I Spy! Was this a feature of your childhood?

CA: I love this! The alphabet game was actually stolen from an ex… But I did invent games as a child to play with my sisters. Another thing I liked to do was adapt the rules of games. We had our own versions of Monopoly and Cluedo which bypassed rules I didn’t properly understand from the instructions. I’m sure some of my adaptations were advantageous to me (I was the eldest), but there was also something very satisfying about changing the rules and how this affected the way the game would work. Mostly, though, I preferred making up games that didn’t have a set objective, which avoided a competitive element. I’m not particularly interested in board games now, but I do like how they reveal the players’ characters, in a way that can be much more direct than through conversation.

BB: What’s next for you?

CA: My mum has always said I don’t make things easy for myself. I recently abandoned a novel I was a third of the way through because it was structurally quite similar to Confessions – characters in different times and places with a thread that pulls the stories together. I decided I didn’t want to keep writing the same kind of novel, and I had an idea for something very different, and difficult. So I’m working on that. It involves quite a bit more research than I’m used to. I’m loving that part of it, but also aware that research can quickly veer into procrastination. Mostly, I still can’t quite believe that I’m allowed to do this, and I have moments where I’m fearful I won’t finish another novel. But that’s all part of it. I’m not sure that ever goes away.

Confessions by Catherine Airey was published by Penguin on 23 January 2025.

Hardback, £16.99