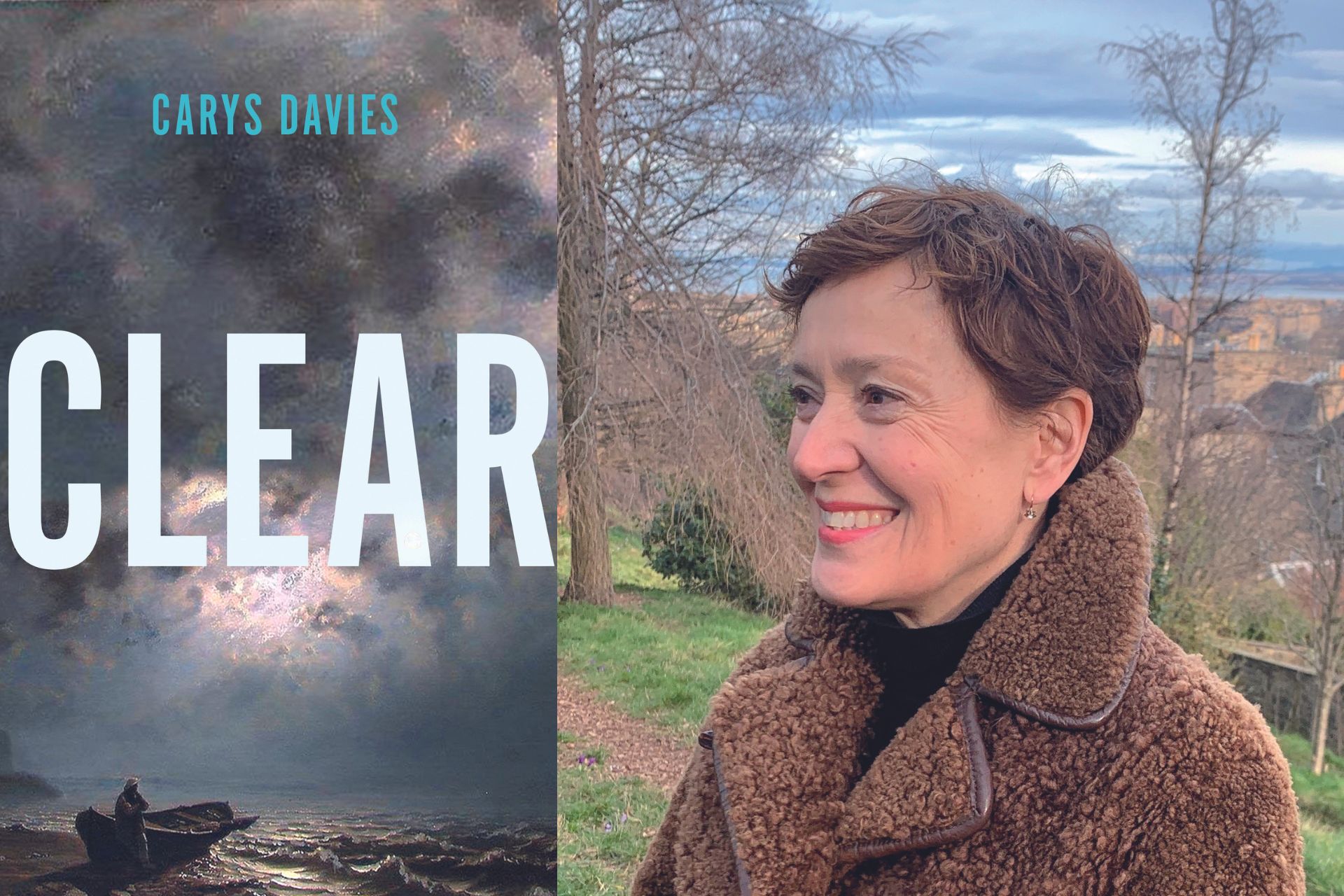

C&TH Book Club: Clear by Carys Davies

By

1 year ago

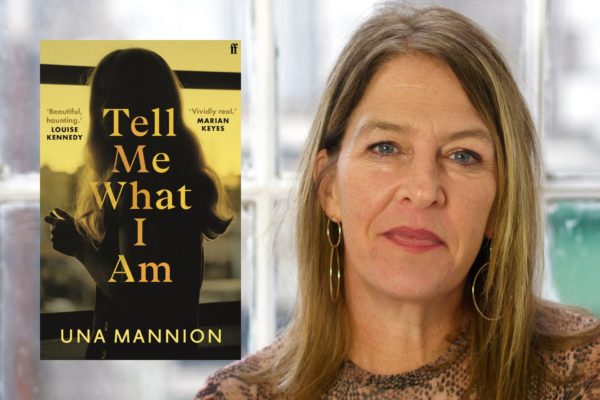

Clear by Carys Davies is out now

In March’s Book Club, Carys Davies talks to Belinda Bamber about libraries, languages and lost souls.

Interview: Carys Davies On Her New Novel, Clear

Belinda Bamber: Clear is about an impoverished, married church minister, John Ferguson, who in 1843 sets out on a perilous mission to evict Ivar, the last inhabitant of a remote Scottish island. What was the seed of the story?

Carys Davies: I do a lot of my reading and writing in the beautiful old reading room at the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh, where I live, and late one winter’s afternoon when I was taking a break from writing, I stumbled across a dictionary in an extinct language I’d never heard of: Norn, which had once been spoken on the islands of Orkney and Shetland but began to die out after the Danish king pawned them to Scotland in the middle of the fifteenth century. There were thousands of words – collected in the 1890s by an indefatigable Faroese scholar called Jakob Jakobsen – between the covers of two ancient-looking volumes, each about the size of a modern hardback novel. I started leafing through them, and I was enchanted. There were a lot of words, as you might expect, to do with the sea and the weather, but there were also others to do with states of mind and emotions, and I knew straightaway I’d come across something very powerful – an extraordinarily rich and precise language which was inextricably bound up with the places where it had once been spoken and the lives that had been lived there. In the years that followed, I went back to the dictionary again and again; slowly the island I’ve imagined in Clear began to take shape in my head, and with it Ivar, who I knew from early on was alone and in some kind of danger, and probably the last surviving speaker of this dying language.

BB: The novel begins as a seasick Ferguson lands on the shore. Why do so many of your stories commence with an arrival or a departure?

CD: One of the first short stories I ever published involved bird-strikes at an airport, and one of the things I discovered about bird-strikes is that take-off and landing are the most dangerous times. I think I’m drawn to arrivals and departures because there’s almost always an element of danger, along with a lot of tension and uncertainty; a feeling that everything has been thrown up in the air and is up for grabs; that we’re on the brink of something. I love that. I never know where my stories are headed. I set out with my characters and see where they’ll end up. That’s what’s exciting to me. If I already knew what was going to happen in a story, I’d never write it.

BB: Your books powerfully evoke a sense of place; do your travels prompt story ideas, or do you visit places to follow up a lead?

CD: The answer to the first question is yes, sometimes my travels do prompt story ideas, but only a long time after the event. So I’ve written short stories set in New York and Chicago, where I lived for a long time, but only after I’d returned to live in the UK. With personal experience there’s a sifting that goes on – things that eventually find their way into a story bed down for years at the back of my mind until they come up against something new; a frisson of some sort that suddenly brings them to life and sets my imagination going. Twenty years after my own travels in the western United States, for example, I read the journals of Lewis and Clark, the explorers. It’s impossible for a European not to be awe-struck by the grandeur of the American West – the sheer massive scale of it – and the journals brought my own sense of wonder, of bedazzlement, rushing back. I began dreaming about an English settler in the early nineteenth century whose reckless journey into the pristine wilderness beyond the Mississippi River became my novel West.

To the second question – whether I visit places to follow up a lead – the answer is no, absolutely not! Quite a few of my stories are set in places I’ve never been: Siberia, the Australian outback. But then I’ve never travelled to the year 1812 either, or to the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, or to ancient Greece. It’s a strange thing, and I wish I could put my finger on how this happens, but the stories I write that are a long way from my own life always feel more real and true to me than those that aren’t. It’s as if I need some sort of distance, in time or space, and very often in both, to see things clearly, and to be curious enough to want to go there. If it hadn’t been for the pandemic, I might have been tempted, when I was writing Clear, to go up to Orkney, just to refresh my sense of the place. I’m so glad I didn’t. I’m so glad I stayed at my desk with Jakobsen’s dictionary and wrote the novel ‘up and out’ from the words themselves. Ivar and John and Mary – they all emerged, like the island itself, from the words, and how they worked on my imagination as I dreamed about this period in history when Norn had pretty much vanished as a spoken language.

BB: Your three novels (and many of the short stories) often feature male protagonists who are lonely, damaged, inarticulate yet wracked by strong emotion, often seeking rescue of some sort. Why is this such a strong theme for you?

CD: I think, just as I need some sort of distance from myself in terms of time and space, I need some kind of distance from my own personality; some way of worrying about the things I worry about, but in someone’s else’s head, and you’re right, very often that ends up being a man’s.

But I’m very interested too, very preoccupied, by the kinds of men I write about. Ten years ago two of my friends, both men, both suffering from chronic depression, committed suicide, and I think in many ways, when I’ve been writing about Cy Bellman in West and Hilary Byrd in The Mission House and John Ferguson in Clear, I’ve been writing in some way about them, and their struggle to survive in the world. The great thing about fiction, of course, is that you can ask the question: ‘What if things had been different?’ and in each book, in different ways, I think I’ve been doing that. Cy, Hilary and John – each of them is a mass of contradictions – between them they are both foolish and noble, curious and blinkered, self-centred and generous, intelligent and naïve, anxious and full of doubt, cowardly and very brave. I love them all.

BB: The women characters by contrast are often physically and emotionally stoic, resolute, reflective and of few words. They have the inner resources of pioneer women. Mary in Clear is a compelling and courageous lead – did you have a sense of her from the outset?

CD: I did, yes. The first scene I wrote where she’s present is the one where John is being briefed by the landlord’s deeply unpleasant factor, Strachan, on how John should go about evicting Ivar from his island. Mary is seething at the cruelty of it all, but after a few brief words of protest, she shuts up, because she loves John, and she knows the reason he’s accepted the job is because he’s desperately anxious about money and wants to be able to put a roof over her head. She doesn’t say much in the scene, but I could hear her voice – her outrage and her dislike of Strachan – and I could feel her self-control, her clear-eyed pragmatism. It’s a difficult but necessary balance for her to have to maintain, and I was immediately interested in what she would do if the situation began to seem to her to be not just wrong, but perilous.

I do think sometimes, in historical fiction, women are given an anachronistic degree of agency, and the women who interest me most are the ones who manage to be fiercely independent, resourceful, and brave within the formidable confines of their time – women like Mary here, or Cy’s feisty ten-year-old daughter Bess in West, or the Quaker spinster Patience Haig in my short story The Redemption of Galen Pike.

BB: Your short stories are notable for unexpected twists that are usually character-led and Clear keeps the reader on tenterhooks; the ending is both unexpected and satisfying. Did you know how the story would end when you started writing? And do you try to write according to the wonderful quote in The Mission House: ‘My best sentences are the ones I begin without knowing how they will end’?

CD: Ha! That’s actually a paraphrase of one of my favourite quotes in the world. The original is a line from the French novelist Stendhal: ‘I spoke much better as soon as I began each sentence without knowing how I should end it.’ For years I had it pinned to the bookshelf above my desk, and by the time I wrote The Mission House it had morphed into the version you asked me about. I love it because it’s so true. Flannery O’Connor famously said that in her short story Good Country People that she didn’t know the bible salesman was going to steal the girl’s wooden leg until he did it. In Clear, something happens about a third of the way through that came as a complete surprise to me; a single sentence that arrived out of nowhere which changed the whole direction of the story.

BB: Your characters are typically full of hope, fear, longing, desire and self-doubt – some, like Ivar, are also remarkably unkempt! – yet dare to take a risk and seize a possibility of happiness or redemption. Why is this theme important to you?

CD: Life is short, and what matters is what we do with the brief time we’ve been given. That’s what interests me – all of us are flawed, but how do we act when the going gets tough? With all the good and bad that’s in us (and no one is beyond redemption), how do we behave in difficult situations that demand courage, or kindness, or an open mind? Happiness comes in many forms, but mostly I think the best definition is that it’s a kind of freedom, and I think most of my characters are seeking that in some way. There are almost always obstacles in the way, of course, both inside them and outside. They all find themselves in complicated situations that involve them negotiating those obstacles, and I’m fascinated to see how they cope with that.

BB: You show a strong moral compass in terms of how your characters treat each other, whatever country or century they live in, without imposing judgements about how they look or dress or co-habit. Where does this rare sense of openness, balance and compassion comes from?

CD: It probably comes from what I said in my answer to the last question, about happiness being a kind of freedom. Everyone has the right to a shot at that. I don’t believe in God and I’m not religious, but my husband was brought up as a Quaker and I attended Quaker meetings throughout my 30s and 40s. It left me with a profound admiration for the way the Quakers practise what they preach – kindness, compassion, independent thought, and a willingness to challenge those in power when they show themselves to be narrow-minded, self-serving, cruel and corrupt.

BB: You also have a finely-tuned sense of human absurdity: Clear contains the only heroine I can think of who has false teeth (and they’re integral to her love story!). Which authors or public figures do you look to for an inclusive approach to human frailty?

CD: Oh let’s see – there are lots, but favourites include Dickens, Gogol, Flannery O’Connor, Miranda July, Flaubert, Dermot Healy, Joyce Cary, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Carson McCullers…

BB: John Ferguson becomes close to Ivar, and to the rhythms of the island, by starting to learn his exquisitely poetic language, Norn. Your pleasure in setting out the many definitions of, for example, ‘a rough sea’, is palpable. Do your language studies give an extra sensitivity to your finely-tuned ear as a writer? And how do international translations refract the meaning of your work?

CD: Language is like bird song, designed so insiders can communicate but also to identify and exclude outsiders, and I’ve always been fascinated by our ability – and inability – to overcome that barrier. At various times in my life I’ve thrown myself into learning French, German, Russian, Chinese, and Arabic, and even though I’m still pretty useless at the last three, it still feels like a kind of magic – like being given a key to a previously locked box. I wanted to convey something of that magic in the way John, in his slow and limited way, picks up the rudiments of Ivar’s language, and through it begins to glimpse the world differently, through Ivar’s eyes.

I do wonder how my translators will deal with the title, Clear, which in English is both a verb and an adjective, and freighted with more than one meaning in terms of what happens in the novel, and I’m not sure it’s possible to pull that off in other languages.

BB: The Scottish land clearances in Clear echo the themes of disruption and displacement by outsiders in your earlier novels, West and The Mission House. The global plight of refugees, in Gaza and elsewhere, is a tragic ongoing news headline around the world. Why are we unable to learn from history?

CD: It’s a good question and a troubling one and it runs through all my novels. Cy Bellman, Hilary Byrd, John Ferguson – they share a kind of blindness, walking into situations they don’t fully understand because they’ve failed to see that there’s an alternative historical perspective.

It worries me that in the UK, and in many other countries, schools are so afraid of courting controversy that the vast majority no longer teach the Israel-Palestine conflict. A number of years ago my husband set up an educational charity, Parallel Histories, to try and tackle exactly this problem.

BB: In Clear, Ferguson’s friendship with Ivar seems to teach him the futility of his religious beliefs – that God’s will could never be ‘consolation’ for Ivar’s expulsion from the island. What is the role of religion in modern lives? I’ve often wondered if your experience of Quakerism has influenced your ability to find light in even your darkest characters. Also if it has impacted the frugality yet richness of your language, in which no word feels extraneous.

CD: It’s important, I think, that at the end of the novel, John doesn’t appear to have lost his faith in God, only in the Presbyterian Church and its adherence to the doctrine of Providence, which teaches that everything that happens to us is God’s will. His friendship with Ivar forces him to examine and ultimately reject that notion.

That’s an interesting question about the pared-back aesthetic of Quakerism and its rejection of flowery religious language in favour of the simple and the modern. Perhaps what’s influenced me is a certain directness: Quakers have no priests, no one who gets between people and what they want to say and I like that.

BB: If you had total financial and political freedom to visit another part of the world, where would you choose?

CD: Antarctica, where I’ve never been, though I’m not sure I’d be up for a whole year. If not there, the Atacama Desert in Chile, where I spent six weeks a couple of years ago and would love to go back.

BB: Your descriptions of the island sometimes powerfully evoke the feelings your characters are unable to express. Are there any plans to turn one of your stories into a movie? Which do you think most apt for the screen?

CD: Whenever I write a scene, I have to be able to see it as a film, so in that respect, the answer would be – any of them! But yes, there are certain stories – West, a short story called The Quiet, and Clear too – where the landscape is both beautiful and terrifying and plays a powerful part and would probably translate very well to the screen. West has been optioned for film, as has The Quiet, about a married couple and their strange neighbour in a remote corner of the Australian outback in the mid-nineteenth century.

BB: You’ve won multiple awards for your books. Do any aspects of writing get easier with experience?

CD: No! George Saunders gets it exactly right when he says (and I paraphrase) that every time you finish a story and sit down to write another one, you get out the same tools you used last time, only to discover they’re the wrong ones. Every story is different and for me it’s a long process of trial and error before I figure out how to write it. The only thing that makes it easier, the longer you do it, is that you know from experience that the long periods of failure, frustration and despair are unavoidable, and that what you have to do is to keep trying.

BB: You were born in Wales and have lived in London, the Midlands, America and elsewhere. What do you enjoy most about living in Edinburgh?

CD: The northern light, and being able to look out at both the sea and mountains at the same time. That, and the Reading Room at the National Library of Scotland, where I love to work in complete peace and quiet.

BB: Which is your favourite library? And what do they offer that can’t be found in online resources?

CD: See above – I also love the manuscripts archive, which is on the top floor of the library. Most manuscript archives I’ve spent time in are gloomy, crepuscular places but this one, with its enormous windows and view out towards Arthur’s Seat, makes you feel you’re half-outside. My best finds have all been in one archive or another – some little piece of gold that’s turned up in an obscure handwritten notebook, letter, shopping list, invoice, or some other treasure, and taken hold of my imagination.

BB: How ruthless are you about pruning your bookshelves and which classics would you keep?

CD: Five years ago when my husband and I moved from a four bedroom house in Lancaster to our two-bedroom Edinburgh flat we got rid of 90 percent of our belongings, including over a thousand books. What we have left are the ones we can’t do without – my husband’s a historian, so there’s a lot of history on the shelves along with everything else. I’m not particularly sentimental about individual editions, which is just as well as a lot of favourite books end up being pressed into the hands of friends or spirited away by my grown-up children when they visit – but I’d be sad if my signed copy of Alice Munro’s Dear Life disappeared!

BB: Which novels are you looking forward to reading this year?

CD: These days I buy most books on Kindle, just because we don’t have space for all the physical copies, but inevitably I’ll be squeezing some onto the shelves this year – I’m especially looking forward to Pity by Andrew McMillan and Long Island, Colm Tóibín’s sequel to the excellent Brooklyn.

BB: Your characters often function quite happily in remote cottages, on clifftops, woods and mountainsides, miles from civilisation. The traditional idea of the writer working from a private eyrie has been totally upended by modern social media. What are the relative merits for you, of engaging with readers in person (eg at signings and festivals), or online?

CD: I’m not on social media so I don’t have an online relationship with readers and I’m happy for it to stay that way. But I really missed meeting readers in person at events in bookshops and at festivals when The Mission House came out during the pandemic.

BB: Finally, you’ve noted before that the writing process is about ‘trying to see the world more clearly’. What did you see more clearly after writing Clear?

CD: One of my favourite lines in the novel is something Mary says towards the end of the novel: ‘You never knew in advance if a decision was the right one. All you could do was try to imagine a future and use that to help make up your mind in a difficult situation, and if you couldn’t imagine the future, well, you had to make up your mind anyway.’

As I said earlier, I didn’t know what would happen in this story when I began it, and I certainly didn’t know how it would end. I think what Mary says here expresses the story’s beating heart: that in life things are rarely entirely clear, but with courage and uncertainty, hope and doubt, love and a generous helping of pragmatism, we do the best we can.

Clear by Carys Davies is published by Granta, £12.99. waterstones.com