Booker Prize Winner David Szalay On Desire, Male Bodies & His New Novel, Flesh

By

10 months ago

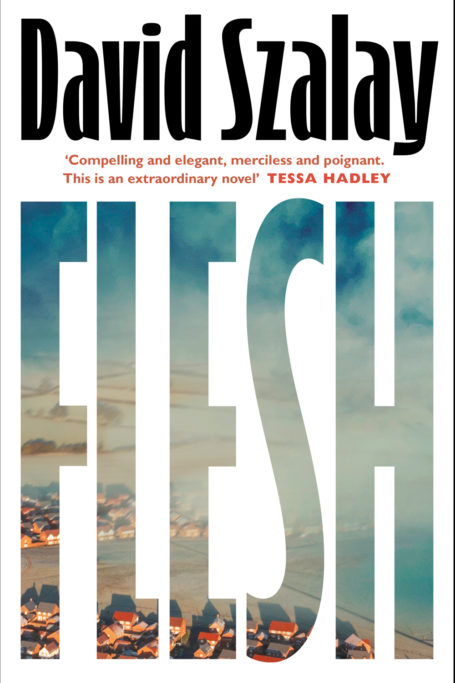

David Szalay's fifth novel, Flesh, is out today – and it's the C&TH Book Club pick this month

In March’s Book Club, David Szalay talks to Belinda Bamber about inarticulate male heroes.

C&TH Book Club: Flesh by David Szalay

Belinda Bamber: The title Flesh is provocative. It made me think of Freud’s corpulent ‘Benefits Supervisor Sleeping’, of meat (das Fleisch) – and sensuality. In fact, although the novel contains plenty of sex, the scenes aren’t explicit. The story feels more to do with how István’s strong, attractive body leads him either into trouble or good fortune. How that carapace influences his actions as a son, a lover, a brawler, a young offender, a soldier, a husband, a man capable of violence but also of being a tender, protective father. Why did you choose that title?

David Szalay: Flesh was my working title while I was writing the book, and although I did expect to replace it with something more ‘literary’, in the end I decided to stick with it. It is, as you say, somewhat provocative. It feels a little vulgar, a little sleazy. But that does perhaps reflect something in the book. And of course the word also has a significant literary pedigree – the Bible, Shakespeare. It combines the tawdry with the profound, the sleazy with the serious, in a way I felt was appropriate. It signals one of the book’s principal preoccupations, which is the inescapably physical nature of our existence, with all that follows from that. And apart from anything else, I think it’s just a pretty strong, impactful, memorable title!

It’s funny you should mention Freud’s painting – I did think of his work in terms of a cover image. Who knows, maybe for the paperback…

BB: How did this story begin for you?

DS: In 2020 I actually abandoned a book that I’d been working on for a few years, and which I’d already written most of. It was a difficult decision at the time, of course, but definitely the right one, and I felt a huge sense of relief when the decision was finally made. But there was also a feeling of huge pressure to make the next one work. The first chapter of Flesh grew from the abandoned book, from one of a few parts I felt were worth keeping. It was quite a challenging process because my confidence had been shaken.

BB: Flesh is your fifth novel: do you enjoy the process of writing, or is it a battle to bring your books to life?

DS: Both, I suppose. I enjoy the process of writing enormously: the experience is often joyful. At the same time, it can feel like a battle – not exactly to bring ideas to life so much as to identify the right ideas in the first place; and by ‘the right ideas’ I mean the ideas that truly engage me, rather than the ideas that I feel ought to engage me, or that I think are likely to engage the reader. To do that takes a certain amount of honesty and self-belief, which isn’t always easy to muster, but if you can do it, if you can identify the ideas and situations and stories that truly engage and animate you, and write only about them, then it’s often relatively easy to bring them to life.

BB: István has echoes of the men in the linked stories in your Booker-shortlisted novel All That Man Is (2016). What inspired you to give him a novel to himself?

DS: From the beginning I envisaged Flesh as formally more of a traditional novel rather than a series of linked stories. But I did want it to have some of the breadth and variety of experience and setting that linked stories allow for. In some ways it has a lot in common with All That Man Is – they are both a series of narratives about progressively older men, it’s just that in All That Man Is they’re different men, and in Flesh it’s the same man at different ages. The chapters of Flesh are mostly quite self-contained, could almost be read as stand-alone stories. They were written like that, actually – each as a pretty much self-contained unit.

One of the things Flesh is about, for me, is the way we change dramatically over the course of our lives while also somehow staying the same. So that the István at the end of the book is extremely different from the István of the first chapter, while also being recognisably the same person.

Also, All That Man Is takes place over the course of a single year, while in Flesh we cover decades of history, so there’s more scope to evoke the ways in which individuals are shaped by historical events that are entirely beyond their control, and how they respond to that.

BB: I was gripped from the first page of Flesh, when adolescent István and a fellow schoolmate discuss whether they’ve ‘done it’ yet. Your novels have been described as ‘realist’. Are you happy with that label?

DS: I certainly don’t mind being described as ‘realist’. I’m undeniably drawn to a kind of realism – as a writer and also as a reader. I just find reality more interesting and more beautiful than anything else. I’m most interested in stories that are very concretely set in my own world – by which I basically mean planet Earth in the late 20th/early 21st century – and that are therefore very specifically about the realities of living in that world.

BB: You’re a master of apparently banal dialogue that somehow reveals character through what’s not said. In Flesh, István’s inarticulacy speaks volumes. Why is this important to the story?

DS: I made a conscious decision to write about an inarticulate character. I guess it’s an aspect of realism, in a way, that I wanted to write about characters who weren’t unrealistically articulate – that is, who didn’t find themselves in possession of well-defined feelings that they were able to express at convenient moments in precisely chosen words. In fact I think that Flesh is partly about the frustrating indeterminacy and intermittency of feelings, and the very slippery and complicated relationship between feelings and the words we use to express them. Unexpressed feelings, or clumsily or partly expressed feelings, or feelings buried somewhere in banal conversations, are often unforgettable.

BB: Flesh can be read as an exploration of manhood – starting with adolescent István feeling overwhelmed by his sexual impulses, through to Kurt’s respect for him as a soldier ‘facing death’, and his hurt when Thomas denigrates him as a ‘primitive form of masculinity’. Is the novel, through its very honesty, a defence of masculinity?

DS: I suppose I wanted the book to be a description, unflinching but also basically sympathetic, of what it’s like to inhabit a male body – or indeed to actually be a male body.

A lot of your questions make an explicit distinction between body and mind – a very traditional distinction of course, very Christian, very Cartesian – but I wanted to move away from picturing existence as a mind somehow ‘trapped’ inside a body. I wanted to look at humans more as bodies that think. It might be that looking at things in that way makes it easier to make sense of human society and history.

Anyway, back to masculinity. Yes, through this book, I did want to explore what masculinity actually is, what it boils down to, and the conflict between István and Thomas was a way of doing that.

Whether any of that constitutes a ‘defence’ of masculinity I don’t know. When I was writing the book, I tried not to think about these things in abstract terms.

BB: I was interested by the parallels between István and his stepson Thomas: each a monosyllabic, neglected only son, though one is from a poor one-parent family in Hungary, the other from an ultra-wealthy couple living in England. Were you making a conscious connection?

DS: There are definitely parallels. But more important is the contrast between them, between the circumstances of István’s upbringing and Thomas’s very different one. There’s a sort of unbridgeable gulf there that is partly a matter of individual character, but also partly about something more general. There’s a certain amount of contempt on both sides, a lack of interest in understanding each other. Their conflict has an air of inevitability about it.

BB: István’s habitual passivity in relationships seems to set the template for his dalliances – often with older women who seduce him. Why is this older-woman theme significant?

DS: I would say that insofar as it has significance, it’s about pattern. I think our lives often follow patterns that are set early, ways of being that are decided almost randomly at first but then become habitual – in István’s case it simply happens to be what you describe.

Although I did also want to look at the dynamics of desire, at the way it’s not a fixed thing, but something that changes and develops in sometimes unpredictable ways.

BB: Your unreconstructed male characters can provoke disquiet among women readers – though the women characters aren’t exactly models of moral high ground, either – and I sometimes rolled my eyes at István reluctantly tumbling into women’s beds. For example, on his early meetings with Helen, ‘he doesn’t even particularly want to have sex with her’ but ‘finds himself looking forward to it sometimes.’ While I’m genuinely interested by the analysis of his desire, that sly ‘sometimes’ feels like a deliberate provocation! (Poor guy!) Are you expecting, or even actively seeking, a reaction from female readers?

DS: I don’t think I’m deliberately trying to provoke female readers in particular!

I would concede, however, that there might be something provocative more generally about some of the stuff in the book.

As I say, a sort of fidelity to experience was one of my guiding principles in writing this (indeed in writing anything) and of course that sometimes leads to uncomfortable places. Not stopping at the point where things become uncomfortable is in way the whole point of the approach.

As you point out, I do try to apply this principle to the female characters in the book as well. (Although for me as a man, writing about female characters is always going to be slightly different than writing about male ones, as the reverse would be for a female writer.)

On the question of female readers more generally, I have to say the majority of praiseful blurbs on the book jacket are from female writers. It probably sounds defensive for me to even point that out… Nevertheless it is true, and it does please me because it gives the lie to the idea that my books are in some way particularly aimed at men – I’ve never thought of them like that.

BB: There’s a funny-yet-awful moment when Helen distracts herself from her husband’s poor prognosis in hospital by casually offering her lover István a blowjob back at the hotel. To me, this scene exposes them both as unthinking, selfish, outrageous, inappropriate. Is it a challenge to you, or to us as readers, to expose your characters at their worst?

DS: The moment when Helen casually offers István a blowjob in the midst of her husband’s cancer diagnosis was in fact specifically discussed during the process of editing the book. Did this somehow go too far? was the basic question. Did it cross the line into deliberate provocation? I wasn’t sure myself. In the end it was decided that no, it didn’t. But what’s interesting is that it was principally male voices that suggested cutting it, and female voices arguing for it to stay.

I’m not sure the scene does expose Helen and István as ‘unthinking, selfish, outrageous, inappropriate’ – or at least while the incident itself might be described in those terms, I’m not sure I would extend that judgement wholesale to the characters themselves, not on the basis of that scene alone.

Anyway, it was decided to keep the incident, and I’m glad we did. If I’m unsparing with my characters it’s because I want to try to have sympathy for them as they are, not as I might want them to be.

BB: István’s mentors help him raise his social station by teaching him English etiquette. When Helen takes him round the National Gallery they pause in front of ‘An Allegory of the Vanities of Human Life’, the Dutch still life with a skull on the table. There’s a strong connection to theme of this novel, in which a sense of death and the ‘corruption’ of the flesh are ever-present. Is it fair to suggest that the vanities of human life are your main subject matter as a writer?

DS: In a way yes, it is fair. The inclusion of that still life – though it’s not actually named in the book – does have something of the significance you suggest.

It is important to stress that I’m not at all down on the pleasures of existence – on the contrary, I’m very much in favour of them. It’s just that I tend to see them in the context of mortality, of transcience, of death.

I find myself in sympathy with many of the attitudes of the pre-Christian classical civilisation of Europe. I think, in our post-Christian society, we’ve ended up in a similar place to the one in which the people of that civilisation found themselves – and of course that’s one of the main roots of our own civilisation. In some ways Flesh is modelled on classical tragedy.

BB: The story of István’s rise and fall is structured in chapters that show his progressively changing circumstances, from soldier to stripclub bouncer to chauffeur to property developer, but unlike Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress, say, many of the major dramatic scenes in his life – including the climax – are only referenced after the event, not as the centrepiece. Why this distance?

DS: I suppose I’m more interested in the consequences that flow from moments of violent drama, than those moments themselves. Also, I think that language as an artistic medium is more suited to that approach. Film and TV have an immediacy and impact that can be quite hard to replicate or compete with for drama. Whereas language has an advantage when it comes to recreating subjective experience. Except that subjectively, there’s a sort of black-out that takes place in violent moments, in moments of extreme anger or fear, that can be hard to convey with words, precisely because words can evaporate in those moments, and experience becomes entirely non-linguistic. That’s partly why there are gaps at those points. Sometimes literal gaps – blank pages.

BB: What’s behind Istvan’s circular narrative, starting and ending in the same place? He does seem to earn some self-knowledge along the way, even a moment of redemption – did you have this in mind when you began the story, or did he surprise you?

DS: No, I knew all along what would happen, at least in outline. That István does find some self-knowledge – and as you say perhaps even something like redemption in a way, at least in the eyes of the observer – was part of plan all along. The story would perhaps be pointlessly bleak without that. The challenge was to avoid moral glibness. And I suppose the circularity of the narrative in a way emphasises the extent to which he has changed.

BB: We only hear István’s voice once, through Helen’s mocking impersonation: ‘”Shoor you can trrrust me,” she imitates, in a thickly accented voice’, which reminds us that he remains an outsider. Did your own peripatetic childhood help your understanding of being ‘outside’ and how does this influence your writing?

DS: I don’t think there’s any doubt that my own life experience of moving countries several times, and of never quite being fully at home anywhere, has hugely impacted what I write about and how I write about it. I’m very drawn to stories about people on the move, people in environments that are alien in various ways. More particularly, my own life for the last decade and more has somehow existed between Hungary and Britain, and I wanted to write a novel that reflected that and drew on it.

BB: You somehow manage to make your characters empathic, despite their objectionable actions. Does it matter if István is ‘not a nice person’ (as one character describes him), in the end?

DS: Is István a nice person? Is he not a nice person? I don’t know, and I was probably deliberately trying to create a situation in which the question is unanswerable, and perhaps doesn’t even make sense. The same applies to the other characters in the book. I have to say that I’m bored by stories in which the morality is easy to grasp, stories in which it’s obvious who we should morally approve of and who disapprove of. Those sort of stories are often not much more than an exercise in flattery – the moral flattery of the reader or viewer. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say that I’m only interested in stories in which the moral questions that are raised are difficult or indeed impossibe to fully resolve.

BB: There are hilarious moments in Flesh. Which humourists make you laugh at the dark side of life?

DS: I do enjoy Martin Amis when his primary aim is to be funny. I think his style only works in a comic mode. As soon as he stops trying to be funny he also stops being interesting. But his early novels, and also in particular The Information, are wonderful and weirdly life-enhancing examples of laughter in the dark. Much of that also applies to Michel Houellebecq – in a strange way, and similarly to Amis, it’s precisely the comedy that gives his books their depth, their humanity. That many people find both of those writers offensive in various ways is probably inseparable from their success as humorists – to be properly, deeply funny comedy has to tap into things that are painful and horrible, and it has to take risks in talking about them. I also regard Kafka as first and foremost a comic writer.

BB: The emergence of Hungary as part of the EU is the backdrop to István’s story. What do you enjoy about living there?

DS: Actually I live in Vienna now, although I still spend a lot of time in Hungary for family reasons. Budapest is a great city in many ways, a very interesting and fun place to live. It’s edgy, it’s vibrant, it still has the feeling of somewhere that’s in the middle of a process of becoming. I was there for quite a few years, and I enjoyed it very much. Obviously, the political situation in Hungary isn’t great – and I mean that whatever the actual shade of your politics, unless you’re actively in favour of widespread elite corruption and cynically manipulative demagoguery. It just became a bit dispiriting to live with that every day, even in Budapest, which as a city is politically hostile to the ruling regime.

BB: Favourite Hungarian novel?

DS: I admire the work of László Krasznahorkai – and think that there’s something quintessentially Hungarian about it – but my favourite Hungarian novel, of the ones that I have read, is probably Fateless (1975) by the Nobel prize-winner Imre Kertész.

BB: You were born in Canada, you were moved to Beirut and then to England as a child, and you’ve lived as an adult in Budapest. You describe yourself as Hungarian-British. Which country or countries currently claim you as ‘their’ novelist?

DS: Canada and Hungary did both make a claim on me when I was shortlisted for the Booker in 2016! And of course I quite enjoyed that. There’s no doubt that, while I can’t claim to be straightforwardly Canadian or straightforwardly Hungarian, I do feel some deep sense of connection to both of those places and it was nice to have that feeling publicly reciprocated like that. I can’t claim to be straightforwardly British either, of course, so it’s a complicated situation.

READ IT

Flesh by David Szalay is published by Vintage on 6 March 2025.

Hardback, £18.99