Interview: Elias Jahshan, author of This Arab Is Queer

By

2 years ago

Straight off the back of a London Literature Festival panel in October

Elias Jahshan, author of This Arab is Queer, is straight off the back of a panel at London Literature Festival. He sits down to talk to us about role models, orientalism and representation in the media.

Elias’ anthology, This Arab is Queer, is an astonishing memoir containing the stories of 18 queer Arab writers. Some under pseudonyms, some under their own names, it jumps across the world to tell the story of the LGBTQ+ Arab community – in their own words.

Interview with Journalist and Writer, Elias Jahshan

Can you tell us a bit about why you wrote This Arab Is Queer and the panel at London Literature Festival you ran with Saleem?

One of the reasons why I pursued it was because I wanted a book where we could tell our stories without the pressing need to respond to a particular headline. Or without the need to feel like we can only share our story to a particular narrative.

When I approached all the contributors, I said that although the overarching theme is about queer identity, their chapter didn’t have to address that directly. Because why do we have to respond to everything? Why can’t we just be you know?

And I said, although there are some stories in there that sort of touch on trauma and stuff, I just told them: don’t feel like you’ve got to tell your readers all this… essentially trauma porn stuff.

And yeah, so the conversation on the panel was essentially about that. And that idea of, you know, how identity impacts our writing.

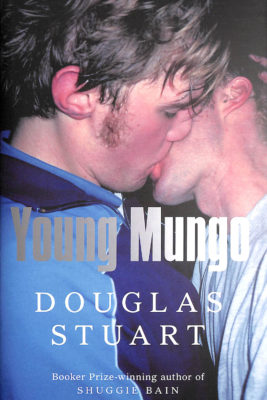

Yes, so I had a few authors join Saleem and I on the panel. But Saleem and I go quite far back! I discovered his novel a few years ago – and although I had known other novels similar before that, which focused on queer narratives, his was the first one that really opened up the doors and helped me discover all these books out there that had already been published. And then he was involved in the anthology as well.

But I was really excited to talk to him more about queer writing at London Literature Festival – and why we need it. Which was really exciting because – it’s just the fact that in London, where the festival was, like, how often do we get such a massive platform to talk about something that is not really spoken of in mainstream media that often. And not only that, to have to be able to have the chance to talk about something like this on our terms, because we’ve asked the lead in the discussion rather than have it talk about us.

Can we actually talk a bit about that – that idea of platforming these stories by the people to whom they pertain?

Yeah, definitely. So, I’m Australian. It’s something that I find is spoken about among indigenous Australians back home in Australia. And I don’t want to [misrepresent] what they say. But one of the common arguments Indigenous Australians make regarding indigenous issues in Australia is, you know, ‘don’t talk about us without us’. And it’s a very common phrase to Indigenous Australians use. But I’ve never really seen it used in any other circles, which you find, which is why I’m very conscious of saying that. I don’t know if it’s my place to say that about Arabs.

I feel like it can easily be applied amongst anything regarding our issues though, or specifically queer issues. You know? If you’re going to talk about queer issues, don’t talk about us without us.

And so, in many ways, that helps combat orientalism, because whenever there’s nobody involved from the community pertaining the discussion that you’re talking about, then in some way you’ll hijack the discussion, and it also has that risk of gatekeeping.

So yeah, I don’t want to talk too much about orientialism. But definitely, I think one of the reasons why this book was published was because of orientalism I noticed in the media.

I was the editor of the Star Observer back in Australia for two and a half years, Australia’s longest running queer media outlet. While I was editing for there, I just happened to be, at that time, the editor when ISIS was running rampant across Syria and northern Iraq. At that time, we got a lot of wire stories from news agencies, about gay men being thrown off buildings – stuff like that. And obviously it was really hard for anyone to access [Syria and northern Iraq], or have the resources to send anyone there. But I just felt like the way these stories were reported on, there was a lot of underlying Orientalism involved and sometimes blatant Islamophobia. And even then after ISIS was defeated, these stereotypes around the region of the world continued.

I feel like having the chance to tell our stories, without people reverting to imperialist orientalist point of views is really important… Because people forget that if we are going to talk about the issues of our border and diaspora, we can’t talk about that without also acknowledging the influence of French and British colonialism in the world. Because under the Turkish Ottoman Empire in the 19th century – or 18th century, I’m not exactly sure it wasn’t until the French and the British came in as mandated colonisers that they introduced sodomy laws criminalising homosexuality.

And I’m not saying that the only reason why we have there’s a lot of homophobia and transphobia in the Middle East. The other side of the coin is that it’s a very toxic, patriarchal society and that plays a role as well. But from my personal experience, I’ve always been told, you know, how can you be Arab and gay when your community doesn’t support the gays. And it’s a generalisation without even looking at the issue from a nuanced perspective.

It is an example of orientalism because it perpetuates a western centric point of view, rather than lets us have the agency to tell our stories.

Thank you for kind of explaining that in such a clear way. Yeah, I don’t think we really get these stories in British media. I can’t think of many TV shows that pertain to queer Arabs or even Arabs in general.

There’s not much. I can think of one episode of Little America on Apple TV. I think the writer was Andrew L. Kennedy, and they’re one of the contributors of my book.

So they wrote this episode about escaping Syria during the civil war, and finally getting asylum in America and what have you – a beautiful story, because it’s just really showing what it’s like truthfully. But I mean, other than that, I can’t really think of anything else.

I mean, I’m sure there is and I don’t want to discount people. But the fact that I can’t think of anything off the top of my head already says a lot.

I wondered if growing up, you had any role models to look up to in the queer community?

Growing up? No, no, no, I didn’t. And I think I think a lot of that has to do with the fact that I grew up in a very sheltered part of Western Sydney. So maybe I just didn’t think to ground. And at the same time, when I was growing up as a teenager, like Google was only just starting up, like, I didn’t really have instant access to Google from the days when I was a child from a baby. So I really didn’t know much about all these big queer icons, role models until after I finished uni and really got into journalism and started to see the world and stuff like that.

That brings me back to this Arab is Queer. Do you hope that it will be providing a space where young queer Arabs can see themselves?

Yeah, absolutely. This is the kind of book that I wish I had, when I was growing up as a teenager. I hope that when young queer people do read this book, they see themselves in the pages.

Elias Jahshan’s book, This Arab is Queer, is available for purchase via Saqi Books, £12.99. Elias was involved in the London Literature Festival on a panel at the Southbank Centre on 23 October 2022.