What Will Cities Look Like In 2050?

By

2 years ago

Peer into the future of urban living

What should cities in our brave new world look like – and can we build them? Ellen Miles ponders the potential urban utopia of future cities where citizens, productivity, community, environment, nature and culture all come together equitably.

This article originally featured in our Great British Brands 2023 book. Check out the digital edition here or grab a physical copy today.

What Will Cities Look Like In 2050?

As recently as 1900, fewer than one in six people lived in urban areas. By 2050, it will be more than four out of six. Picture your city in 2050. What do you see? A vague image of glass and flying cars? Or a more dystopian scene? To have any hope of realising a viable, fair, regenerative future, we need to relinquish hasty assumptions and pessimism, and create clear visions of what cities can, and must, look like.

Transport: Moving Forward

By 2050, anti-car planning and policies will have led to (almost) car-free streets, with remaining vehicles fully electric. Many roads will have migrated to well-lit, fume-free underground networks – freeing up precious surface-level space for public amenities. These tunnels will assist, not disrupt, ecological processes: take Kuala Lumpur’s 9.7km Stormwater Management and Road Tunnel (SMART), which combines transport with flood control. Along with cycle-lanes and highways, and app-ordered, electric vehicles, reliable high-capacity and carbon neutral public transport will leverage drops in tunnelling technology costs. Look to Hyperloop, which is developing electric shuttles travelling at speeds up to 670 mph, three times faster than high speed rail, and ten times faster than traditional rail – making a London to Paris journey in under 30 minutes.

Subterranean shuttles will also revolutionise product delivery. British tech scale-up Magway, drawing investors like Ocado, is developing a ‘completely trackable, super secure’ zero-emissions postal network in London, capable of transporting tens of thousands of parcels an hour, timed ‘down to the very second’.

‘Sky bridges’ will be far more than walkways, with homes, offices, restaurants and more. We’ve seen the New York High Line repurposed as a public park, and Washington DC is soon to unveil its 11th Street Bridge Park. They will be facilitated by innovative engineering technology like Multi, a rope-free Willy Wonka-esque lift, which uses a world-first cable-less system that allows it to travel both vertically and horizontally.

The ’15 Minute City’

Everything in reach

What will be done with the remaining ground space? A planning (r)evolution presently underway is moving away from the 1930s ‘Athens Charter’ (advocating the separation of residential and business zones) towards the ‘Leipzig Charter’, whose guiding principle is a walkable city of diverse, multi-use, space-efficient neighbourhoods. This includes the idea of a ‘15 minute city’, in which residents’ essential needs – including employment, food, lifetime learning, social connection, nature and leisure amenities – are a short walk or cycle from home. The 15 minute model will reinstate cities as a collection of villages, each with its own character and community. Bringing diverse industries and functions close together will shorten supply chains, and create opportunities for hyperlocal, renewable energy solutions: a 2020 world-first scheme saw waste heat from the London Underground warming 1,350 homes, two leisure centres and a school in Islington.

Shopping in these villages will be different from shopping on today’s high street, with hubs focusing on independent, local businesses, resulting in a renaissance of workshops and ‘smiths’: think cobblers, tailors and tech-smiths. For everyday supplies like grains, oils and cleaning products, refill stores will be the norm, as will having them delivered to your door through brands like Charrli, the milkman-style kitchen and bath product refill service. Beyond refills, the world of food will be localised through produce swaps and hyperlocal small urban farms, and underground and indoor hydroponic farms.

Social enterprise Incredible Edible is leading the charge on community-led growing in the UK, while visionary guerrilla gardener Ron Finley is empowering communities to turn food deserts into food sanctuaries in Los Angeles.

Complex planning for myriad, often competing needs in small spaces will be assisted by tools like Delve, created by the Google-owned urban innovation organisation, Sidewalk Labs. Its software creates optimal design solutions for neighbourhoods, factoring in considerations like residential space, energy usage, natural light, transport access, and walkability.

Multi-Purpose Spaces

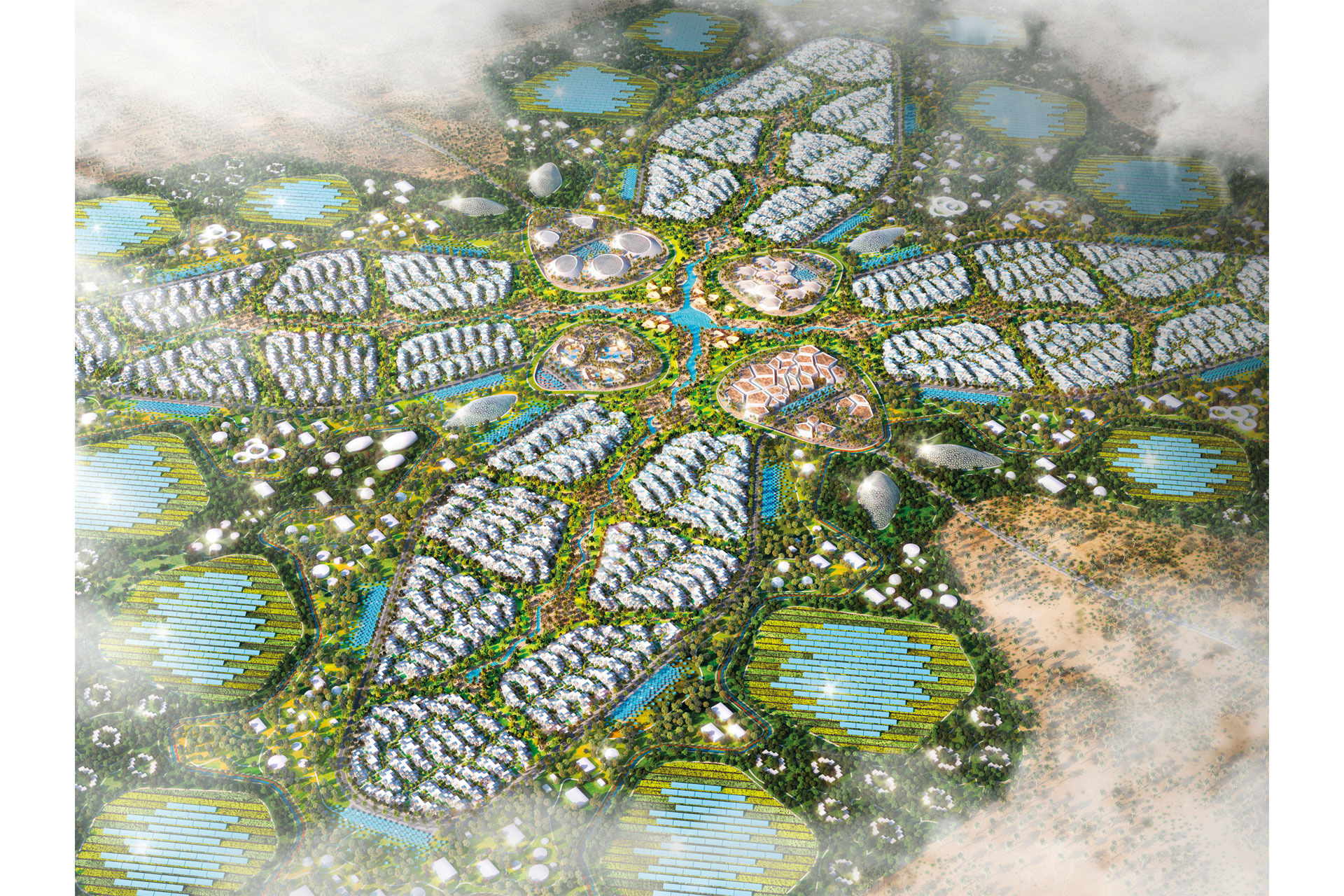

URB, a sustainability consultancy specialised in creating the future of urban and sustainable living, have rendered here an entirely self-sufficient city

Buildings will be multi-purpose spaces in which to work, learn, relax and connect, used differently at morning, noon and night – remaining alive and dynamic around the clock and calendar. The Bouldering Project, a daytime bouldering space, becomes a music venue at night and also functions as a workspace with a mezzanine offering a broad shared desk or high bar seating for hot-deskers. Such spaces appeal to diverse groups – artists, entrepreneurs, community leaders, academics – creating opportunities for ideas exchange across disciplines.

Vicky Spratt, author of Tenants: The People on the Frontline of Britain’s Housing Emergency (Profile Books, £20), says the past holds many lessons: ‘Le Corbusier thought buildings could form the vertical version of a street, with shops and other amenities – which is why he put a nursery school, a paddling pool and running track on the roof of La Cité Radieuse in Marseille.’ She cites the internally pedestrianised Barbican, filled with cooling, beautiful green and blue space, as inspiration. ‘We can build safe, secure, decent, and truly affordable housing that’s environmentally and socially conscious,’ she says. ‘The thinking just needs to be joined up, and the funding needs to be there.’

By 2045, the UK’s population of over-85s will have almost doubled since 2020 to 3.1 million, 4.3 percent of the population. Laura Macartney, co-founder of InCommon, a social enterprise that creates intergenerational bridges between young and old, says, ‘We need to build infrastructure that bakes intergenerational connection in. This means co-located services, spaces designed with all ages in mind, and multi-generational housing.’ Japan, which has the world’s oldest population, has already pioneered its Yoro Shisetsu centres, combining care facilities for children and the elderly. In West London, the Nightingale Hammerson care home and Apples and Honey nursery share an address.

Multi-purpose spaces will be agile, effective, largely co-owned and co-managed by local communities, under an agreed set of rules and responsibilities, simultaneously providing a response to the housing crisis. It’s not a new concept and already such spaces are working, like 12 Claremont, a former printing factory. It was recently bought by the Hastings Community Land Trust to become ‘an explicitly inclusive, creative, and affordable neighbourhood hub for living, working and community action’.

As an alternative to current top-down urban planning models, placemaking uses the skills, knowledge and creativity of people who (will) use a space as capital to design, build and manage it. By 2070 citizens will actively co-create their cities. Postcode gardeners will maintain public nature, providing nature connection to the landless while eliminating the need for toxic chemical herbicides. Land around critical state-managed infrastructure, like transport and hospitals, will become urban commons, with workshops, plays, gigs and sports days bringing communities together. We will no longer be defined as ‘consumers’ (read Jon Alexander’s essay for more on that, too) but active citizens. What we create and do, rather than what and where we spend, will form the basis of our impact on our city. The word ‘city’ comes from civitas, the Latin for a body of citizens, the community. This concept will be felt in the bones of every 2050s city.

Green Dream

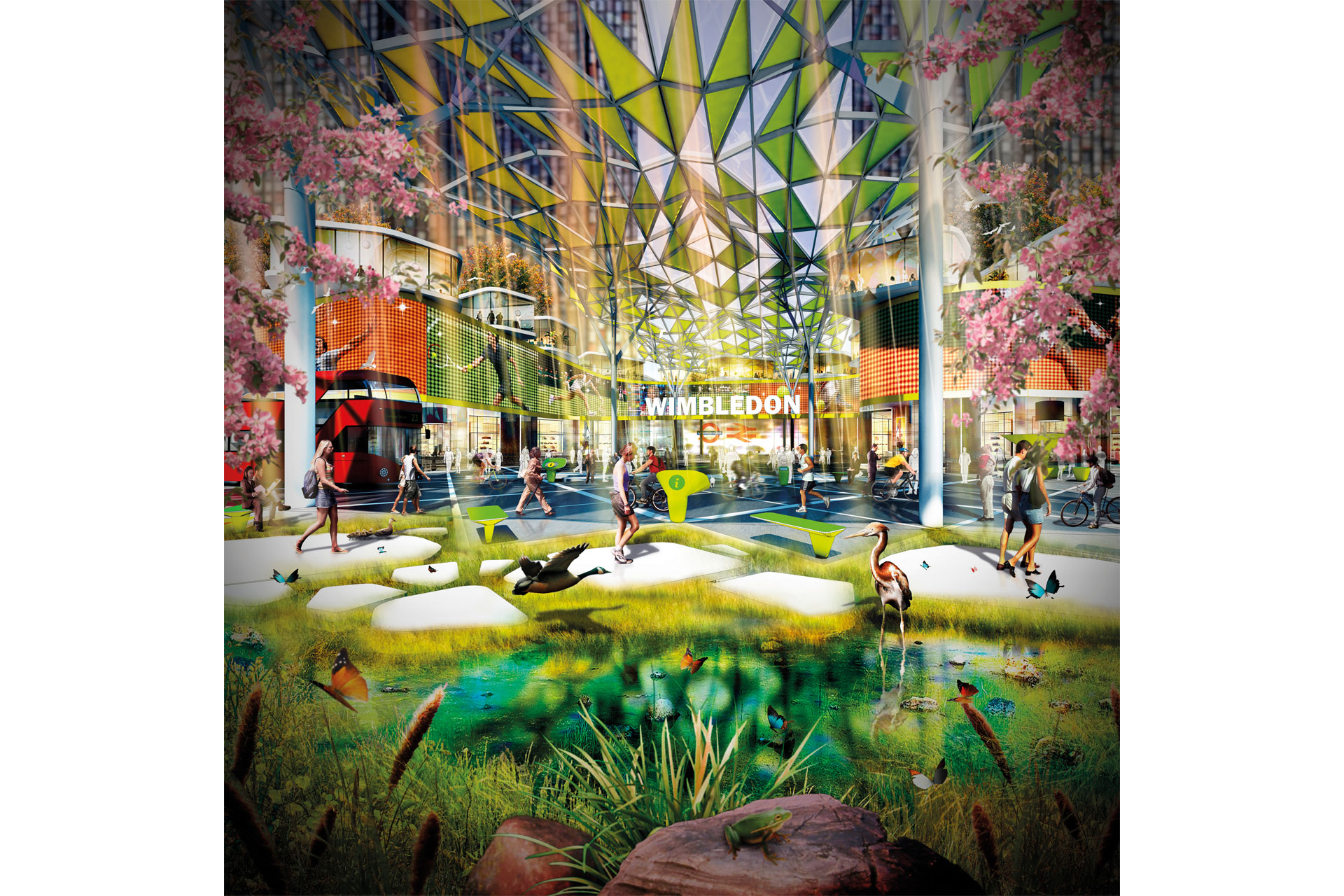

A rewilded urban space

The metropoles of 2050 will be green with biophilic infrastructure and architecture abounding. We’ll see green walls, rooftop allotments, pocket parks, tree- and hedge-lined streets, and ponds. People will be paid to rewild their lawns and depave their driveways; companies will get subsidies for incorporating (and maintaining) habitat-making and -connecting features for birds and pollinators into their office façades. Policies will provide legal protections and rights to organic entities and ecosystems.

Nature will work hard to reduce the heat island effect, mitigate flooding, and clean the air. The proposed ‘Forest City’ in Liuzhou, China, provides an early template with every house, office, hospital, school and shop covered in plants. Outnumbering its 30,000 residents, the city will also be home to 40,000 trees and over a million plants.

Engineer Rudi Scheuermann proposes a time- and cost-efficient way to cover high-rise walls with plants: just roughen the surfaces and species will naturally settle and flourish, as they do on cliffs. As water conservation becomes a prime concern and temperatures rise, processes like xeriscaping – which reduces or removes the need for irrigation by selecting heat-hardy, low maintenance, drought-resistant plants – will be vital.

Internal spaces will be green too. Workspaces like Second Home already have biophilic interiors, with bright, natural-light-flooded spaces filled with plants, including full-sized trees, and neat, healthy moss patches covering unreachable sections of floor.

It’s not concrete that makes a city – it’s culture. Cities are a kaleidoscopic clash of stories, a farrago of rhythms. They are playgrounds for ideas, swathed in the shimmer of art and the hum of music and conversation. Drag queens mingle with mechanics, poets rub shoulders with politicians, and footballers fraternise with florists. None of this demands concrete, pollution or stress. Twenty fifty’s cities will be alive with nature – and so even more alive in creativity, colour, soul and spirit.

Street-Smart

Big Data and the Internet of Things will make cities more accessible, inclusive, and safer for all. This includes auditory and visual cues for deaf and blind people. Tokyo, home to the world’s busiest subway station, Shinjuku, with 3.5 million using it daily, plays birdsong from subway exits, and sounds on escalators help blind people navigate. In Los Angeles, street lights flash warnings of oncoming ambulances.

Looking Ahead

Today’s cities, designed under neo-liberal capitalism, prioritise cars and commerce over community and climate – a value set inconsistent with future-proof resilience. To ensure their – and our – survival, all cities must start to centre social and ecological good. To achieve the future cities the world needs, it is citizens who must act. Leaders in policy, industry and community must act on a hyperlocal level, and value social and environmental concerns on a level with economic ones. In an increasingly hostile climate and with urban population booms, these changes must be made – and are already in progress. A brighter future is possible. Will you help to build it?

Images by URB.