Mission Possible: Making Fashion Sustainable

By

4 years ago

‘Without these sustainable brands driving forwards, nothing changes. But with them, everything can change, including the very idea of the purpose of fashion’

As an industry that potentially contributes up to 10 per cent of global emissions, fashion’s reckoning day is here. Some brands though are ahead of the curve, says Lucy Siegle.

Mission Possible: Making Fashion Sustainable

Let’s not sugar coat this: we know we are in the throes of a dual climate and nature crisis. This summer the UN secretary general, Antonio Guterres, warned the latest IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) represented a ‘code red for humanity’.

The fashion industry bears more than a little responsibility. After all, the fashion industry’s greenhouse gas emissions are estimated to be up to 10 per cent of the global total; the sector is one of the top ten polluting industries on Earth; northwards of 100 billion garments are produced each year from virgin resources; 87 per cent of clothing material is incinerated, consigned to landfills or dumped in the natural environment and we buy 60 per cent more clothes than 15 years ago, wearing them for half as long. According to analysis by the campaigning NGO, Changing Markets, synthetic fibres represent over two-thirds (69 per. cent) of all materials used in textiles, a figure expected to rise to nearly three-quarters by 2030.

Mother of Pearl Brenon jacket, £295

I know, I know, that sounds so depressing. However, rather than despair, we need active hope, as opposed to the passively hopeful printed messages offered by fridge magnets. The Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres, who brokered the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, says we need ‘stubborn optimism’. She describes this force as an unshakeable determination to choose systems and ways of living that flip from exploiting the Earth to nurturing it.

Well just at the right time, when we need it most, the UK has produced a collection of sustainable fashion brands, often led by visionary CEOs that seem to me to embody exactly this. I have been tracking sustainability and analysing sustainable fashion in the UK for nearly 20 years. Looking at the work and progress of some of the brands we bring together in this edition of GBB was a restorative experience. In a ‘code red’ scenario, these are the brands that give hope and direction.

There is no legal definition of ‘sustainable’ in fashion, so it remains open to interpretation (and greenwash or overclaiming). But to me it means three core things. First, sustainable fashion design and production must respect the planet’s boundaries. Second, we must ‘balance’ and only take what can be replenished. Third, we have to acknowledge that all species and landscapes (nature) are interconnected: you can’t damage one without impacting another.

Amy Powney, creative director of Mother of Pearl, definitely gets it. I have lost count of the times I have heard fashion editors marvelling about the superb fit of her dresses – and that remains a very important box to tick, especially in these days of rental (in April this year Mother of Pearl teamed up with OnLoan to offer a rental arm). But she is also known for being incredibly driven. ‘Sustainability isn’t a one-dimensional issue that can be solved by opting for a fabric with green credentials; the final fabric is just the tip of the iceberg and what’s looming underneath is rarely considered or examined,’ Amy said recently. ‘Supply chains are not straightforward, so social, environmental and political factors must be taken into account when looking at manufacturing with any country.’

Christopher Raeburn at work

To me this is so on the money. Fashion is a full spectrum industry, from the picking of the fluffy cotton bol, the spinning, ginning, weaving and clattering of looms, right through to the bit that gets the most attention – the marketing, the shows, the selling. As it whirrs through continents and processes, a garment builds up an astronomical debt to Planet Earth. The brands we feature here know this industry feels Earth’s every heartbeat. For instance, when Himalayan glaciers melt and affects a monsoon, the fashion industry feels it through a depleted cotton harvest, which also takes a huge toll on the people who produce the cotton. Farmers are as much a part of the fashion value chain as designers.

Great sustainable brands don’t just feel it, they account for their ecological debt too. Over the years, I have interviewed Stella McCartney often. Each time she emphasises that her brand is far from perfect, yet the percentage of her collection she refers to edges up a little. For pre-fall 2021, the percentage of her collection made up of sustainable material had reached 80 per cent. ‘It’s the highest number I’ve ever achieved, but it wasn’t easy getting there,’ she told the fashion press. As always with Stella, the claim was accompanied by evidence, worked out via careful eco accounting, which goes into quite some factual detail. For example, the use of brass on some pieces accounted for 77 per cent of the brand’s water pollution impact, due to mining.

OK, for some this will be too much information, but Stella has the ability to turn dry sustainable theory and carbon accounting into inimitable pieces that are both desirable and a lot of fun. In her world, global change comes via bio-based, recyclable, faux furs and forest regeneration translates into big chunky boots made from sustainable wood.

And to me that’s the job of a sustainable brand today too. You have to drive the mission along. Stella McCartney is the great mainstreamer of ecological ideas, moving them away from the mere chatter of the climate bubble to centre stage. Who else, when fashion waste was still something of an untold story, would elect to photograph her 2017 winter collection in a Scottish landfill site, the model lying in beautiful dresses on top of junked cars and everyday consumer detritus? It was a characteristic provocation designed to move the debate forwards.

RÆMADE Air Brake dress, £645, made from parachute material

Eliminating fashion waste is often a core part of a leading sustainable brand today. For East London designer, Christopher Raeburn, liberating surplus fabric (often military fabrics, in his case) drove him from the off. ‘It was a love of fabrics that first started REMADE,’ Christopher said, when he founded his eponymous menswear brand in 2009. ‘What’s really exciting is taking an original item and completely reworking it. It gives us such a unique selling point and our customers get really excited about the authenticity of the fabric.’

To me, Christopher Raeburn is king of telling and selling the story of the fabric. His design breathes life into surplus fabrics and deadstock; great coats, parachute silks even a 24-man life raft and a fighter-pilot compression suit can be refashioned into his signature outer wear. But he is also king of democratising sustainable style. Most sustainable brands do not try hard enough to involve customers who are priced out. But Christopher, who is also global creative director for Timberland, has formed meaningful collaborations with Depop (the reuse marketplace) to produce a sunhat pattern and with Aesop (the cosmetics brand) to produce a DIY accessory case. In this way, he comes across more as a movement builder than a traditional fashion brand.

His positive influence, and that of many of the brands featured in this issue, are increasingly obvious in the wider industry. Earlier this year luxury conglomerate LVMH announced it was launching an online marketplace for its ‘deadstock’ fabric and leathers. The fashion industry loses an estimated £120 billion per year in unused deadstock (Queen of Raw) so of course there is a commercial logic to using it. But in a conservative industry like fashion, where the burning and dumping of unsold stock has become the norm, you need fire-starters like Christopher Raeburn. Without these sustainable brands driving forwards, nothing changes.

But with them everything can change, including the very idea of the purpose of fashion.

Sustainable fashion must be about people as much as it must be about carbon emissions. Like Christopher, Cameron Saul and Oli Wayman define their fashion business as one that uses craft and artisan skill to create positive social impact. Bottletop was launched in 2002 through a design collaboration with Mulberry and a bag made from recycled bottletops. It has grown into a luxury brand with atelier and training programmes in Brazil and Nepal. But these days you’re likely to see luxury brands at United Nations conferences using Bottletop’s bracelet #Togetherbands, made from upcycled materials, including decommissioned AK47s from child soldiers, to push forward the Sustainable Development Goals.

A volunteer harvests flax

Make no mistake, the mission of a sustainable fashion designer has grown, and today’s brands will intervene where they need to. It made sense to see Stella striding up to world leaders at the G7 summit in Cornwall agitating for curbs on unsustainable fashion – obviously looking fabulous in strappy heels and a blue dress. ‘I’m really here to ask all of these powerful people in the room to make a shift from convention to a new way of sourcing and new suppliers into the fashion industry,’ she said, ‘One of the biggest problems that we have in the fashion industry is we’re not policed in any way. We have no laws or legislations that will put hard stops on our industry.’

Doubtless there are some that would prefer to see business as usual and no hard stops. They have failed to grasp that on a planet of climate shocks and ecological collapse there won’t be business for any brand. But now the leading sustainable brands don’t just hold the line, they go deeper, much deeper.

Ten years ago in California, Rebecca Burgess, an expert in natural dying, founded Fibreshed, with the idea of taking locally grown fibre for fashion to market, reconnecting fashion to farming using textile crafts. What excites me about this revolutionary approach is that it is not restricted to making fashion’s impact ‘less bad’, which was the definition of sustainable design when I first began tracking it. Instead, it focuses on fibre and ecosystems to regenerate, both the soil and atmosphere (natural fibres grown in a natural cycle can store carbon) and to regenerate the very culture and beating heart of fashion.

In Blackburn, Homegrown Homespun, the Fibreshed affiliate for Northwest England, is a life affirming project from textile expert Justine-Aldersey-Williams and Patrick Grant, the affable designer who appears on TV’s Great British Sewing Bee. Patrick has been such a champion of regional, sustainable fashion, through his Community Clothing brand and Super Slow Way, an art programming project that works with communities along the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. With a team of dedicated volunteers, Homegrown Homespun has planted flax and woad, two of the UK’s forgotten fibre and dye crops, on urban land. Following a pair of indigo linen jeans from the experimental first crop, the idea is to upscale production by 2023. The point here is not that Homegrown Homespun can singlehandedly challenge the global reliance on synthetics. Of course, it can’t and won’t. Nor is it an historical re-enactment, although the fact it’s planted in the heart of the North West’s historic textile industry resonates. Rather, this is an ambitious example of how a healthy fashion supply chain looks – short and transparent, climate beneficial and linking farming to fashion. It is both a counter point to the craziness of what passes for mainstream, and an advertisement for how functional, nurturing and logical our fashion system can be. It serves as a reminder to all of us stubborn optimists that the most important collaboration any of us will ever have is the one with planet Earth.

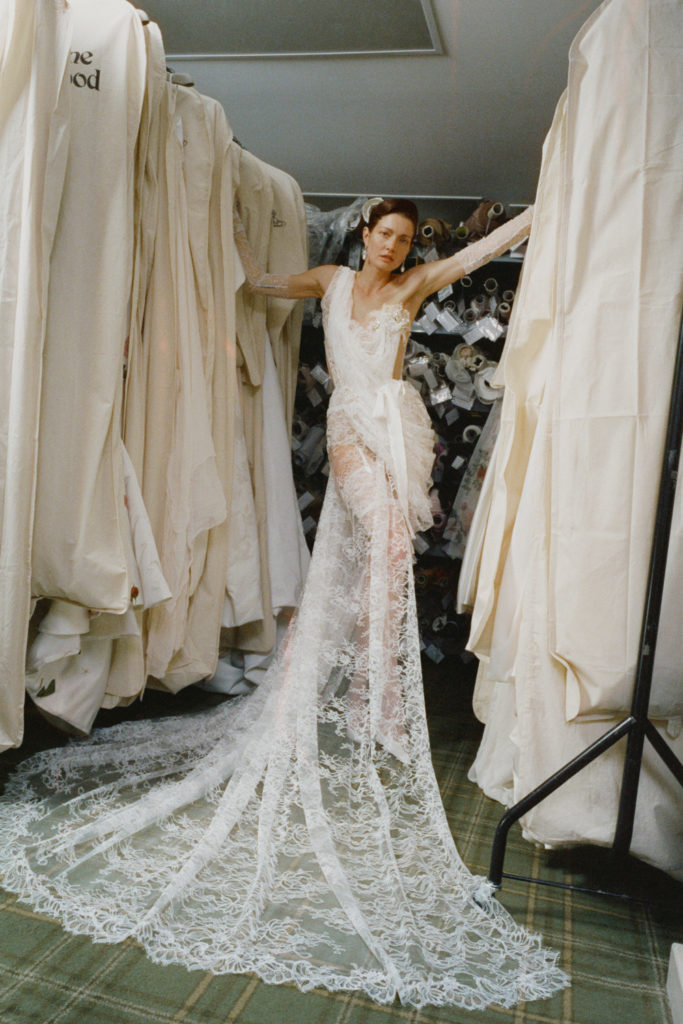

Featured Image: Stella McCartney AW‘21

Read More: