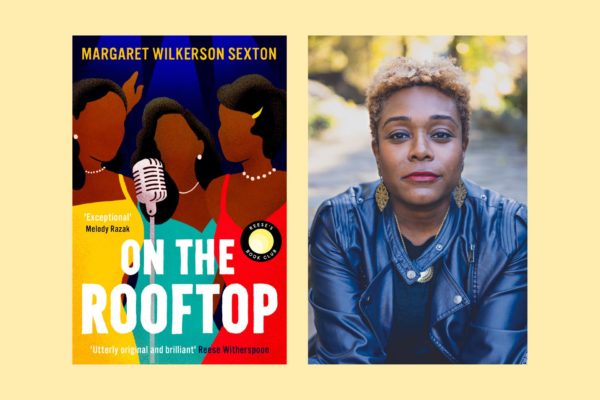

C&TH Book Club: Happiness Falls by Angie Kim

By

1 year ago

Mystery awaits

In February’s Book Club Angie Kim talks to Belinda Bamber about moving from Korea to America as a child, becoming a novelist at 40, and creating a central character who has autism.

C&TH Book Club: Happiness Falls by Angie Kim

Belinda Bamber: Happiness Falls is a novel about a close-knit Korean-American family whose lives in Virginia are overturned when the kids’ father, Adam, goes missing. His 14-year-old son Eugene, who is non-verbal, becomes a suspect, and the story is narrated by his daughter, Mia. When did you first hear her distinctive voice?

Angie Kim: Mia’s voice has been with me for over a decade! She was the narrator in one of the first short stories I ever wrote, which won a literary prize and was published ten years ago. I had a lot of fun with her snarky, intimate voice, and her voice and her family – a biracial family (like mine) with a Korean immigrant working mom, a white stay-at-home dad, and three kids – stuck with me and wouldn’t leave me alone.

Several years ago, while freewriting in Mia’s voice, I wrote: We didn’t call the police right away. I immediately saw in my mind what had happened to her family: her father and youngest brother go out for a walk, and only Eugene returns home, frantic, upset, and bloody. Where is the father? What happened to him? And that tone of deep regret in that voice – why didn’t they call the police? What does Mia wish she’d done differently? For the following three years, I holed away in my writing closet (yes, I literally write in a closet!) and wrote to find the answers to these questions and follow this quirky family’s quest to communicate with Eugene and find their father.

BB: The distinctive trait of people with Angel Syndrome like Eugene is that they smile and laugh even when they’re not feeling happy. Have you experienced that sense of being trapped inside your head, unable to express who you are?

AK: Absolutely, and it’s one of the most foundational experiences I’ve had. When I was eleven, I immigrated to the US from Korea. I didn’t speak any English, which was frustrating and isolating, but it went beyond that – to shame. I realised for the first time that our society has a deep-seated assumption that equates oral fluency with intelligence. When I couldn’t speak, I felt like a bah-bo. A stupid person stripped of all thoughts and words.

It got worse when I learned English to where I could understand but still couldn’t speak it. Kids talked about me in front of me, making fun of my heavy accent, weird syntax, and ‘broken’ English – even as they were smiling at me, pretending to be friendly. It was humiliating, and I smiled to cover up my embarrassment, which is something that many nonspeakers have told me they do as well. I became fluent in English after a few years, but that experience profoundly impacted me. Writing this now, over 40 years later, I still feel that burn of shame.

BB: The theme of this issue of C&TH is Transformation, and I was struck by a key transformation in Happiness Falls, when the family starts to realise that their determined, courageous and loving efforts to get inside Eugene’s head are barely scratching the surface of the person he is inside. As the mother of three boys with medical health issues, how did your personal experience influence this depiction?

AK: I love that moment when the family begins to realise that although Eugene can’t speak, he does have words – they’ve just been trapped inside his mind all his life. One of my kids had dyspraxia (oral motor issues) and was an extremely late talker, and in the course of trying to figure out why, we discovered that he had ulcerative colitis and coeliac disease, which resulted in malnutrition and developmental delays. I remember the intense joy when we treated the issues and he started growing and running and, yes, talking, all the thoughts that had been trapped in his head just pouring out. And along with the joy, the guilt of not having known about his pain all along, of not having figured it out earlier. I wanted to capture that gut punch feeling, that combination of wonder and devastation.

BB: Did the process of writing the novel change anything for you?

AK: Absolutely. I write using a process I call ‘method writing’ (similar to Method acting, which I studied at Interlochen), in which I try to inhabit the mind of the point-of-view narrator as much as possible, which really helps with empathy and understanding. But even beyond that, the research I did for the novel with respect to alternative communication methods led me to discover a wonderful organisation close to my home, which provides training and therapy for nonspeakers to communicate through spelling on a letterboard. I started volunteering several times a week, teaching creative writing to nonspeakers (mostly autistic teens) – something I’ve become very passionate about and definitely plan to continue.

BB: The Stephen Hawking preface quote – ‘It’s a crazy world out there. Be curious’ – is apposite both for Mia’s lively, questing character and your novels. You show deep empathy for human short-sightedness and confusion, balanced with a scientific desire to analyse and understand. Adam’s theory about the Happiness Quotient is a perfect example and resonated with me long after finishing the book. Where did it come from?

AK: I’ve been fascinated by theories and studies about quality of life and happiness for as long as I can remember, and many of Adam’s musings are based on my own scribblings throughout the years. I think my interest probably stems from my experience as an immigrant – having been really poor but very happy in Korea and then completely miserable my first years in America even though my family was so much better off objectively. I puzzled over this in college as a philosophy major, researching and writing about theories of objective versus subjective happiness, and I came to believe that your happiness is relative to your baseline – not based solely on the experience itself, but on the comparison of that experience to your expectations based on your ‘normal’.

When I started working on Happiness Falls, one of the first things I did was to build spreadsheets in an effort to quantify some of my ideas about happiness. (I used to be a management consultant and I love building spreadsheets!) After filling in the numbers for many hypothetical situations involving joy and misery, I arrived at a formula involving division, with the resulting answer (the quotient) being the predicted happiness level.

BB: What is pure happiness for you?

AK: Reading a book I love by the ocean while sipping wine (preferably a big cabernet franc) on a bright sunny day. Or going out for a great movie with my family and then debating its merits over a long, hearty dinner.

BB: What do you miss about living in Korea?

AK: I loved the simple day-to-day aspect of my family’s life in Seoul. We were very poor, and my parents and I lived in one tiny room of another family’s house, with a rusty water pump and an outhouse. (We didn’t have indoor plumbing.) No bed, no colour TV, no fancy clothes, no electronic toys, not even books – due to the lack of space, I was allowed to borrow only one book at a time. But I remember the closeness with my parents, playing Korean jacks with my mom and challenging my dad to a round of Go. I remember my mom making me special lunch treats whenever she could: ghim-bop, seaweed rolls with daikon radish, scrambled egg strips, and carrots; or yoo-boo-bop, sweet sticky rice tucked inside a doll-sized pillowcase made of fried tofu. When we moved to Baltimore in the US when I was eleven, we gained so much in terms of material wealth—refrigerator, indoor plumbing, my own bedroom – but I lost the closeness with my parents because they had to work 18-hour days at a grocery store in a dangerous part of town far away.

BB: How do you feel about literary genre labels and does that influence how you approach a story?

AK: I’m wary of literary genre labels because they can so often be misunderstood and confining. For example, if you call a book ‘thriller’ or ‘mystery’, some readers will assume the book is plot-heavy and fast-paced with less emphasis on character development or prose. Even though Happiness Falls (like my debut, Miracle Creek) contains a mystery element, I think of that as a Trojan horse of sorts. The investigation becomes a device, a container to hold together all the stories I want to tell about this family’s past and current lives. My favorite authors tend to combine different genres in each story and also jump around genres from project to project – Kate Atkinson and Kazuo Ishiguro come to mind – and I would love to do the same, to write the stories I want to write in whatever format/style/voice most appropriate for them without regard for how they’re eventually going to be categorised.

BB: You graduated from Interlochen Arts Academy, studied philosophy at Stanford University and attended Harvard Law School, where you were an editor of the Harvard Law Review. You became a legal advocate and then a dotcom entrepreneur. Given the chance to start over, would you take a more direct path to becoming a novelist?

AK: Not at all. I didn’t start writing until my 40s, after many other jobs/careers, the longest and hardest of which was being a stay-at-home mother to three boys with medical issues. If I’d started writing earlier, I would have missed out on all those life experiences that gave me insights into the criminal justice system, office and intra-family politics (particularly gender dynamics), sibling relationships, mommy wars, health insurance debacles, and so many other things that inspired my writing. Much of my writing research is organic, learning through direct experience, and I wouldn’t give that up for the world.

BB: The end of Happiness Falls intriguingly leaves some questions unanswered. Are you generally someone who seeks solutions in life, or are you able to live in the margins of uncertainty? Which approach is more valuable as a novelist?

AK: Tana French recently wrote that there are two types of mysteries: those that restore order (such as detective whodunits) and those that explore how we cope when order is impossible. As much as I love when there are simple, neat, easy solutions to problems in real life, my favourite stories – the ones I reread and recommend to my dearest friends – are the ones that teach me how it feels to be in those impossible dilemmas when there are no easy answers, when you need to struggle and think and try and fail and try again. That’s one of the reasons I chose to write about a missing person case, which to me are the deepest, most intriguing mysteries because the range of possibilities is so vast, encompassing everything from the most horrific (kidnapping and murder) to the most innocuous (took a fun trip without telling anyone). Most missing-person cases in real life go unsolved, and yet, most of those stories in novels, TV, and film choose to embrace the “fun” whodunit elements of those cases and depict neat, certain endings. I wanted to interrogate that and emphasise the more real-life side – the struggle and confusion of questioning everything about the person you thought you knew and the relationship you thought you had with them. How do you survive the unknowability? I need help coping with that in real life, and writing about it helped me with that, as I hope it will for readers, to read about it.

BB: At what age did you realise you were a storyteller?

AK: I didn’t start writing until I was in my 40s, and I published my debut novel the week I turned 50, so I should probably answer that I was 40-something. But looking back, I’ve been a storyteller all my life. I was an avid reader, but back in Korea, growing up, my family was very poor and we all lived in a tiny room with no space for books, so I was allowed to borrow one book at a time. This meant that I re-read books over and over, and spent a lot of my free time acting out what happened in between the written scenes and after the book’s ending. I fell in love with acting, especially improvisational work, which is essentially creating stories. And my first career as a trial lawyer involved telling my client’s side of the story to the judge or the jury. So I think the more accurate answer is that although I didn’t start writing stories until my 40s, I’ve been a storyteller since I was a child in Korea.

BB: Your debut novel, Miracle Creek, was garlanded with awards and rave reviews. How does it feel to approach your second book launch?

AK: It’s been really nerve-wracking! There’s a lot of imposter syndrome at work here, wondering if people will say the success of my debut is a fluke. I keep trying to remind myself that my happiness is relative to my baseline, and that my baseline is not the author who wrote Miracle Creek and won awards. Rather, that my baseline is the unpublished writer who started writing stories with no idea whether I could finish any of them, let alone get an agent, have a publishing deal, walk into a bookstore and see my name on a book with a beautiful cover on the front table. Once I remember that, I realise how happy that old baseline-me would be at knowing where I am now, working with amazing editors and publishers I admire, meeting readers at bookstore signings, and doing wonderful interviews like this one.

BB: Will you be coming to the UK?

AK: I’m not sure yet. But I lived in Oxford for a half-year in college and loved travelling throughout the UK, including Wales and Scotland, and coming back to London numerous time and Belfast and Dublin a few times as well, for work. I’d love to come revisit any/all of those places!

BB: Which books are you looking forward to reading in 2024?

AK: I’m really excited to read Kiley Reid’s Come & Get It, the late Korean-American writer Katherine Min’s posthumous novel The Fetishist, and Tana French’s The Hunter. And I absolutely loved my dear friend Julia Phillips’ Bear.

BB: Which classic narrative has most profoundly touched and influenced you?

AK: I love Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince. I first read it in Korean as a little kid in Seoul, and then I read it in French as a high-school student in French class. When I was in my 20s, one of my best friends from law school asked me to serve as a bridesmaid and read a scene from it for her wedding. She gave me a copy, marked with the scene she wanted me to read, which was about how we “tame” those we love by taking care of them and nurturing them. That was the first time I read it in English.

I remember how much it affected me, not only that scene but the whole narrative, how things that appear a certain way from the outside hide what’s truly inside. In particular, I love this quote, which I chose as an epigraph for Happiness Falls: ‘One sits down on a desert sand dune, sees nothing, hears nothing. Yet through the silence something throbs, and gleams. “What makes the desert beautiful,” said the little prince, “is that somewhere it hides a well.”‘

Happiness Falls by Angie Kim is published on 1 February by Faber & Faber (£16.99). faber.co.uk