Interview: Author Jessie Greengrass on Climate Anxiety and Motherhood

By

3 years ago

London Literature Festival will host Jessie for a panel on climate change

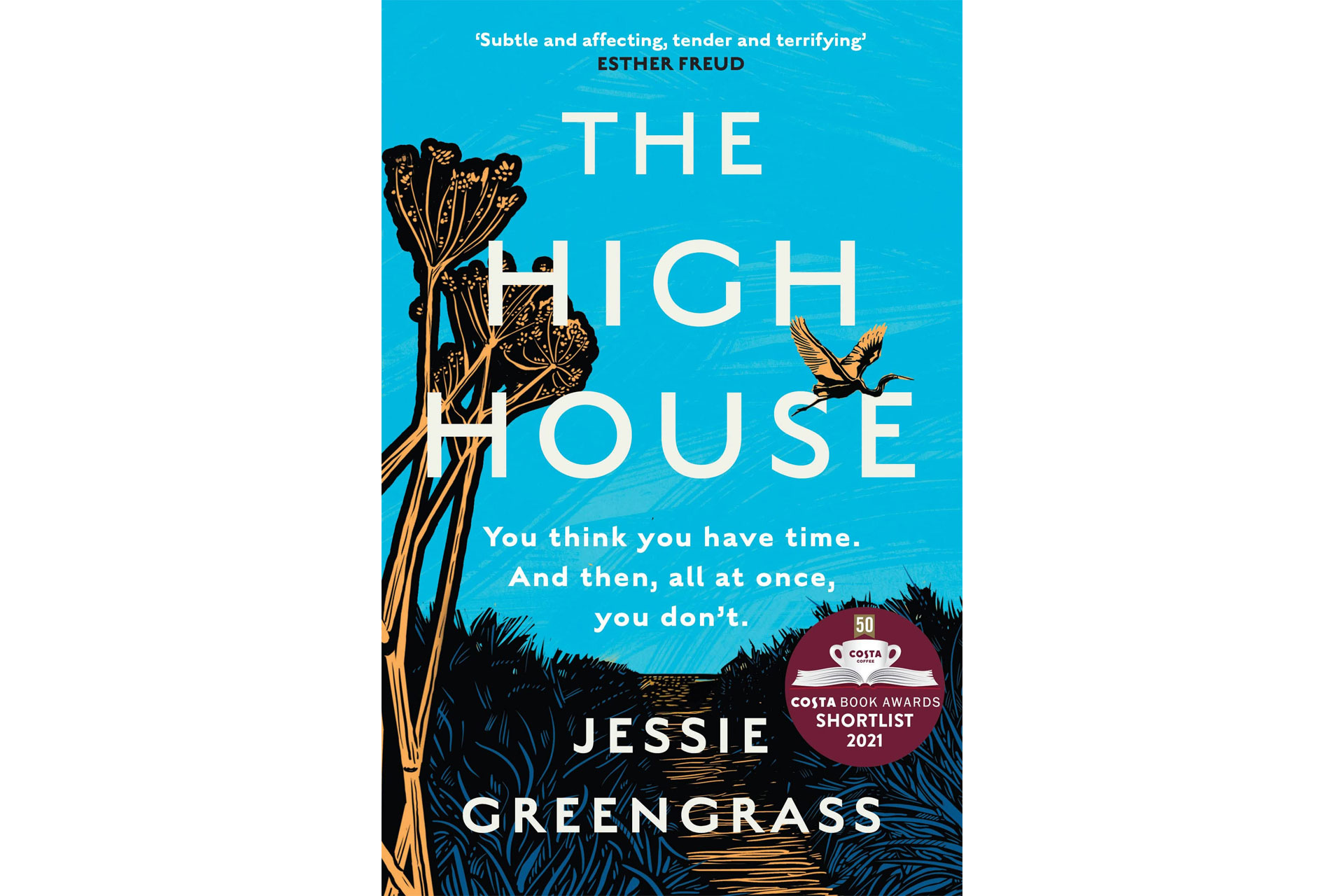

Author Jessie Greengrass’ novel The High House is a hyper-realistic take on a British landscape ravaged by climate change. Shortlisted for the Costa Best Novel Award 2021, this is a must-read for environmentalists and dystopian fiction lovers alike. She talks to us ahead of the London Literature Festival.

Jessie Greengrass is among the many sparkling authors lined up for the Southbank’s London Literature Festival as part of its climate strand. She talks to us about her connections to the venue, urban environments – and her climate anxiety for her children.

The C&TH Guide To the London Literature Festival

Interview with Jessie Greengrass

Let’s jump right in: did you always want to be a writer? I know you studied philosophy at Cambridge.

I sort of got into writing by accident. I studied philosophy at Cambridge and wanted to pursue that further. But my mum got very ill in my last year at university, and I had to come back home to look after her. And then she died a year later. And I sort of lost, you know, I didn’t know quite what to do after that. I kind of didn’t really feel like I could go back to philosophy.

I’m sorry to hear that. Where did it take you next?

So eventually I was working in a box office at the Southbank Centre, and I just sort of needed some kind of outlet, or I needed to feel like I was working on something, I think. And actually, lots of people who were working there were trying to start out in creative careers or trying to make their own way. So it felt like a bit of a community and it grew from there. I never decided that I was going to try and be a writer, it just sort of happened.

Life can be very roundabout in its path. Working at the Southbank Centre, can you tell me a little more about that?

Front of House was full of a lot of young people in their early to mid to late 20s. Some musicians, some people working in visual arts. To me, it felt exciting. I actually think that one of the things that art centres can forget is that providing those jobs is a vital part of their role. Like they have sort of emerging artists programmes, and those are really wonderful. But an even better thing to do is to say, right, we’re going to staff our building, you know, with those sorts of flexible but reliable jobs that allow you to work around the edges alongside lots of people who are trying to be artists.

And eventually, was there a point where it changed – when you were no longer the person trying to be an artist, but you could say, you know, I am an artist?

I suppose when my first book [came out], it was kind of then…

Actually, A lot of things happened at once. When I got the contract to publish my first book, I was also pregnant with one of my daughters. Which has also kind of meant that the whole duration of my ‘proper’ writing career has been very much tied in with looking after small children. Sometimes it depends on the day as to whether I feel like I’m doing more one than the other, you know. Sometimes I really hesitate to say that I have a writing career.

I’d love to talk about the London Literature Festival, if that’s okay – can you tell me a bit more about your panel with Daisy Hildyard?

I’m really excited. I think it’s going to be a really interesting conversation. And they, both Daisy and Jess, (who is going to be the moderator), are interesting writers and have really interesting things to say about climate change specifically. Although it always feels a bit sort of daunting before an event because you don’t quite know which direction to go in!

And on your book, The High House – obviously it focuses on a lot on climate change and nature? Did you grow up in the countryside?

So, I grew up in Devon in North Dartmoor, and we lived there until I was in my early teens, and then my mom and I moved to East London. Which was really sort of jarring. While I was writing the book, I think I was trying to get back to a landscape that I had truly loved. I was tapping into that sense of loss.

I do think though that it’s really easy to talk about nature writing in terms of remote landscapes or kind of ‘pristine landscapes’, but you know, urban environments are also environments. There’s also nature there. It’s important and needs protecting, and people’s experiences of it are as important as people’s experiences of rural landscapes.

I actually wondered if writing the book changed how you thought about the land around you, or if it’s just reaffirmed the way you already do?

I guess now… I’d kind of thought that I would be able to walk to the beach, and you know, see a seal and just be happy – you know, about wonderful it is to be close to nature like that. But now it’s impossible to do that without this niggling fear that of what’s happening to the seal populations and what they’re experiencing in a sea that is full of plastic and warming up, you know, so that I think that my book really kind of was a way of sort of thinking my way through that and addressing that real sadness. And, you know, probably anger as well, I guess.

Do you think that you feel a level of climate anxiety? Is that something you want the book to impart?

Yeah, I would hope so. But also, I mean, I was writing the book in 2019. So it feels like things have just changed so much, even in the space of just two years.At the time, it felt like this conversation wasn’t happening, you know, it felt like people weren’t addressing it. And now it feels like we’re not ignoring anymore. But that’s because it’s so bad that it’s unavoidable, and it’s been really weird to have that experience, particularly because one of the things that I wanted to write about in the book was how I couldn’t understand how things had gotten so much worse in my lifetime. Like, I can remember the late 80s, early 90s, worrying about saving the whales or the hole in the ozone layer – and maybe global warming was going to be a thing. And then suddenly, it’s like, everything rushed by and now here we are, and London’s got dehydrated squirrels flopping around on the floor. The grass is dead. And so I think that that was the thing that I was really trying to get at in the book. And then obviously in the, in the two years since I wrote, like, that’s just speeded up. It’s something that I don’t know how to make sense of,

I’m literally going to quote you: you think you have time, and then, all at once, you don’t. Does it resonate differently with you today than when you wrote it in 2019?

I think that if I was writing it now, it would be a lot more angry. Really, you know, I really do. And also that the things that I was thinking about when I was writing it particularly stuff about climate change and colonialism, you know, sort of felt like a nascent idea – that that they were connected.

And I was trying to unpick how those things were connected and I think that if I was writing but now I would be much clearer on this. Because it’s absolutely the habit have of thinking of people and environment and the world as resources. And it’s exactly what’s enabled us to get here. We can’t think of people as being disposable, just because they’re far enough away…

I feel like my thoughts on that have got much clearer. And I feel really strongly about it. And, you know, like, we’ve always been fine. People have droughts in other places, but we’ve got resources, we can turn the aircon on, or we can bus water in.

But for me it’s about fully understanding that being the last man standing doesn’t make you a survivor, it just makes you the one that has to turn the lights off,

I wonder if you’re involved in any climate activism following this – especially feeling that anger?

No, not nearly as much as I feel like I ought to be. What I’m hoping to do though, as now my children are a bit older, is to get involved in climate activism in a way that can involve them. And certainly my bigger daughter, my oldest, is very keen to do something.

Do you feel anxiety for the generation ahead, as this comes across in the novel, is that how it feels with your own children sometimes?

Yeah, much more now than again. When we were thinking about having children, it didn’t really feel like it was something that I needed to think about at the time, that oh maybe we shouldn’t. But recently there was a point where I just had to say I can’t talk about this anymore, because I can’t think about what this means for our children’s lives, you know? And I realise that saying I can’t talk about it is a terrible, terrible response.

It isn’t terrible: it can feel like a pretty overwhelming wave. Plus you’re doing your bit.

Yeah, in so far as I’ve written the book, and I’ve had a lot of conversations about it. But I still want to do more and then again I have two small children and it’s difficult to find time. But maybe, if it’s important enough, you should and this is something that I was thinking about in the book – with Francesca. Like, if it’s important enough, maybe actually you can’t just say I’m really sorry, I’ve got small children, I’m busy.

That’s really interesting. I actually wondered if you know, talking of that kind of activist, Greta Thunberg is going to be the London Literature festival headliner?

I didn’t know that. That’s really nice. When I was writing the book, I was trying to imagine Francesca. And I imagined her as if Greta Thunberg kind of got older and had two kids. Although Francesca is a real complicated character, so I would not want to say that I based her on anybody. But it was thinking in terms of the young people now, who are very active in climate activism, projecting them forward kind of twenty years and saying, what would it be like if you had children?

Jessie Greengrass will be talking about the imminent emergencies of everyday life with fellow author Daisy Hildyard at London Literature Festival. Catch them as part of the festival’s climate strand at the Southbank Centre on Saturday 29 October. Her book, The High House, is available for £14.99.