Leah Thomas on Climate Fatalism, Eco Anxiety, and the Dark Side of Green Energy

By

3 years ago

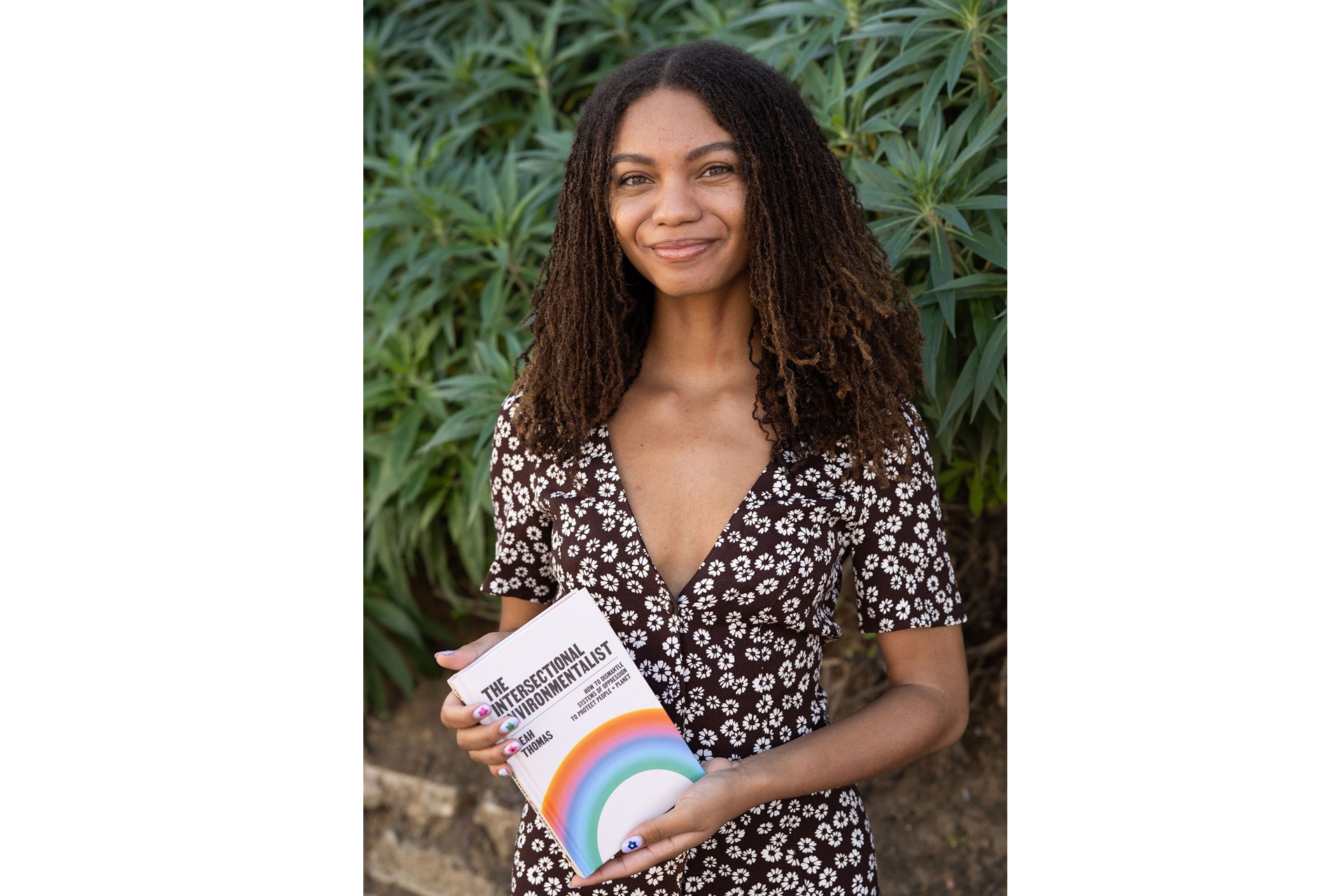

Catching up with the author of The Intersectional Environmentalist

C&TH sits down with eco-activist and communicator Leah Thomas to talk about her new book, The Intersectional Environmentalist, as well as climate fatalism, eco anxiety, and the dark side of green energy.

Main image by Cher Martinez

Q&A with Leah Thomas of The Intersectional Environmentalist

AW: What’s your story so far?

LT: I’ve always loved ecology and nature, and growing up I thought I wanted to be a veterinarian. When I finally went to college I initially studied biology, but it wasn’t really clicking with me for some reason, so after my first year I decided to switch to environmental science and policy.

During that time it was the start of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States. Because that coincided with my environmental studies, and I was really passionate about racial justice, I was really looking for ways to infuse the two, because I didn’t want to be ‘okay, on Monday I’m an environmental activist, and on Tuesday, I’m a racial justice activist.’

And I started looking at data about how I could do both of those things, because women, people of colour, and low-income folks are the most impacted by the climate crisis. That’s how I got the early idea for what intersectional environmentalism could look like.

At the same time there was also the first women’s march in the United States, and there was lots of talks about feminism, racial justice and the climate crisis, and that’s how I learnt about intersectional feminism.

I started my own blog talking about intersectional environmentalism. I worked at Patagonia on the communications team, and that got me really excited about comms and how to make environmental language more accessible. And then I decided to leave my job during the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, and start The Intersectional Environmentalist organisation, and that’s when I started writing the book.

Green Brands Recommended by Sustainability Pioneers

What was your green lightbulb moment?

I always felt like I had a different passion for the environment than some of my classmates; I was one of the only black students in the class. I really cared about the Earth, but I also cared about the urgency of the present. We were talking about the climate crisis and how it’s going to impact us 30, 40, 50 years from now, but there are people in low-income communities, and Black and Brown communities, that don’t have clean air right now. I was struggling internally with the urgency of the present, and I felt there were so many issues we needed to address right now, from how oil and gas is impacting people’s water supply, or how pollution in certain areas is leading to respiratory illnesses.

So instead of saving a future world, it’s fixing the world as it is now, and fixing the injustices happening right now?

Yes, and climate fatalism is huge among Gen Z – they think that there’s nothing we can do [to save the planet]. Imagining that apocalyptic world is causing a lot of eco-anxiety. And I think we could inspire more climate optimism if we take it one step at a time and focus on the present; if you focus on an area that’s local to you, that has a lack of trees, or green spaces, and you come together as a community to build a garden or fight to plant more trees in the neighbourhood. And that’s a small change that will go a long way and will make the future better. I think those little changes at the local level will inspire people and leave them feeling more optimistic, because I’ve seen too many apocalyptic films and I don’t want to be scared anymore.

In the book, you write ‘intersectional environmentalism is the lens, while environmental justice is the goal’. What exactly is environmental justice? And how do we reach that goal?

Environmental justice came from the Civil Rights Movement in the US, from the days of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jnr. In the UK and Europe, I hear [the term] ‘climate justice’ used more.

It comes from the 1980s, when the first civil rights activists started looking at how toxic waste was placed in communities of colour, and low-income communities. They just started presenting data on who is being the most impacted by different environmental hazards and toxins. ‘Environmental justice’ just means ensuring that everyone has equal access to environmental human rights: that your air is breathable, your water is drinkable, that you have safe working conditions, etc.

You write in another chapter about the dark side of green energy, which I found fascinating, because you don’t hear much about that.

This was the most shocking for me, too. It’s happening all over the world and I think people don’t hear a lot about it. Because if a government chooses to transition to green energy, that’s something that’s usually praised, despite any damage that is done along the way. But those aren’t small inconveniences if you are taking land from indigenous folks or polluting their water in the process. There are so many case studies – on everything from nuclear energy to lithium mining – of how the health of indigenous folks is impacted by green energy.

Something else that really got to me was the lack of climate reparations, because a lot of green energy projects are happening within indigenous communities. And they’re not paying people. They’re coming to indigenous lands, they’re setting up lithium mining, and they’re paying people pennies, even though their livelihoods might be impacted, like their waterways, etc.

I think one way to make green energy transitions a lot more ethical for all people on the planet is to make sure that indigenous folks have representation every step of the way, as well as employment. Lithium mining [for batteries for electric cars] is bringing in billions, if not trillions of dollars, globally each year, and we need to make sure that with this green energy transition there can be climate reparations and funding going back into the communities that have been impacted by not only green energy, but historically also oil and gas.

Who did you write the book for?

I like this question. Probably for my younger self in some ways. This is the book I wish I had in my first year as an environmental science student. It’s for people who are starting their environmental journey or their intersectional environmentalist journey, so when they’re learning about other things they can always ask the question, ‘who is being most impacted?’

It was to validate my younger self as well. If anyone tells you that [the link between] racial justice and climate doesn’t exist, here’s a bibliography of 500 references that proves them wrong.

What does the planet’s ideal future look like to you? And how do we get there?

This shouldn’t be controversial, but I just want people to breathe clean air and drink clean water. Really basic things that still require a lot of systemic changes.

I want people to feel safe in their environment, from environmental hazards, and also from social injustice and discrimination. I know utopia isn’t possible, but if we shoot for the moon, as they say, we’ll land in the stars.

What’s the one thing we could all do to help the planet?

Get involved in local efforts. Find out what’s going on in your city and your community, and try to get on board. And you’ll learn a lot when you work with organisers who are already doing amazing projects, but just need some help.

Find out more about Leah’s work at intersectionalenvironmentalist.com and order the book at uk.bookshop.org

READ MORE

Discover More Sustainable Content at C&TH