Is Lucian Freud A Great Artist? – ‘New Perspectives’ Exhibition Review

By

3 years ago

Ivan Lindsay unravels the work of Lucian Freud

Ivan Lindsay surveys the works of one of Britain’s most prolific artists at the ‘New Perspectives’ exhibition at the National Gallery, and asks whether Lucian Freud is really a great artist

Review: ‘New Perspectives’ at the National Gallery

The exhibition of the work of Lucian Freud currently showing at the National Gallery in London has been jointly organised by the National Gallery and Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. It marks the centenary of the artist’s birth and brings together 76 works spanning his life. It is a rare occasion to see so many of Freud’s works in one place and gives the viewer a chance to decide just how accomplished he was as an artist. He was certainly a good artist – but was he a great one?

Such is the reputation and image of the artist that it requires effort to put that aside and let the works stand or fall on their own merit. Freud’s reputation was built on his family background, his charisma, his brutal working practice of countless sittings per portrait, his dedication, his eccentricity, and his chaotic lifestyle with numerous partners and children.

The exhibition catalogue acknowledges that Freud’s life was predisposed to public attention because he was the grandson of the famous psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. The artist built on this by surrounding himself with illustrious friends and acquaintances, ranging from people drawn from the criminal underworld to the aristocracy. Freud was proud of his grandfather, and when he took his friend, the artist John Craxton, to visit his recently deceased grandfather’s house in Maresfield Gardens in 1941, they took ‘turns to lie on the legendary couch’. While Freud was grateful for the increasing royalties he received from the Freud Estate, he resented when his background overshadowed the artistic quality of his work, admitting to ‘having read scarcely a line by my famed grandparent’ and wanting ‘to be known only through my pictures’.

Lucian Freud, Girl with Roses, 1947-8. Oil on canvas. 105.5 x 74.5 cm. Courtesy of the British Council Collection © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022/Bridgeman Images

There has long been a suspicion that the art world needed a new face and that Freud arrived at the perfect time. In 1993, the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin wrote to this effect when reviewing the Freud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Although she acknowledged a ‘genuine admiration for genuine gifts’ – such as the ‘achievement’ and ‘formal and expressive triumph’ – she believed these ‘scarcely account for the degree and amount of uncritical adulation lavished on Freud’s production’ and rejected the ‘enormous psychic investment on the part of so many patrons, critics and curators’. She continued that these insiders need to fill ‘the art world position vacated by the death of Picasso with the most likely candidate’, for which ‘in terms of both style and persona, Freud plays the Great White Western Male Artistic Genius to perfection’.

Freud was born in Berlin in 1922. When Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, he and his family emigrated to England. He went to various English boarding schools and art colleges, and the family were naturalised as British subjects in September 1939. Lawrence Gowing, who first knew the artist around 1939, described him as a ‘boy wonder’ and said he was ‘fly, perceptive, lithe, with a hint of menace’.

The first works included in the exhibition are a strange group of naive paintings dating from 1940, when the artist was just 18. There is a self-portrait (Cat 1) dated 1940, a portrait of his art teacher Cedric Morris (Cat 2) of the same year, and a group portrait entitled ‘The Refugees’ (Cat 3) of 1941. This group of works would not be recognisable as by Freud unless you were told they were, and feel most similar to the middle European ‘School of Paris’ Jewish artists such as Emanuel Mane-Katz, Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall and Moise Kisling. These works do not hint at what was to come, and the treatment of the faces and hands is weak.

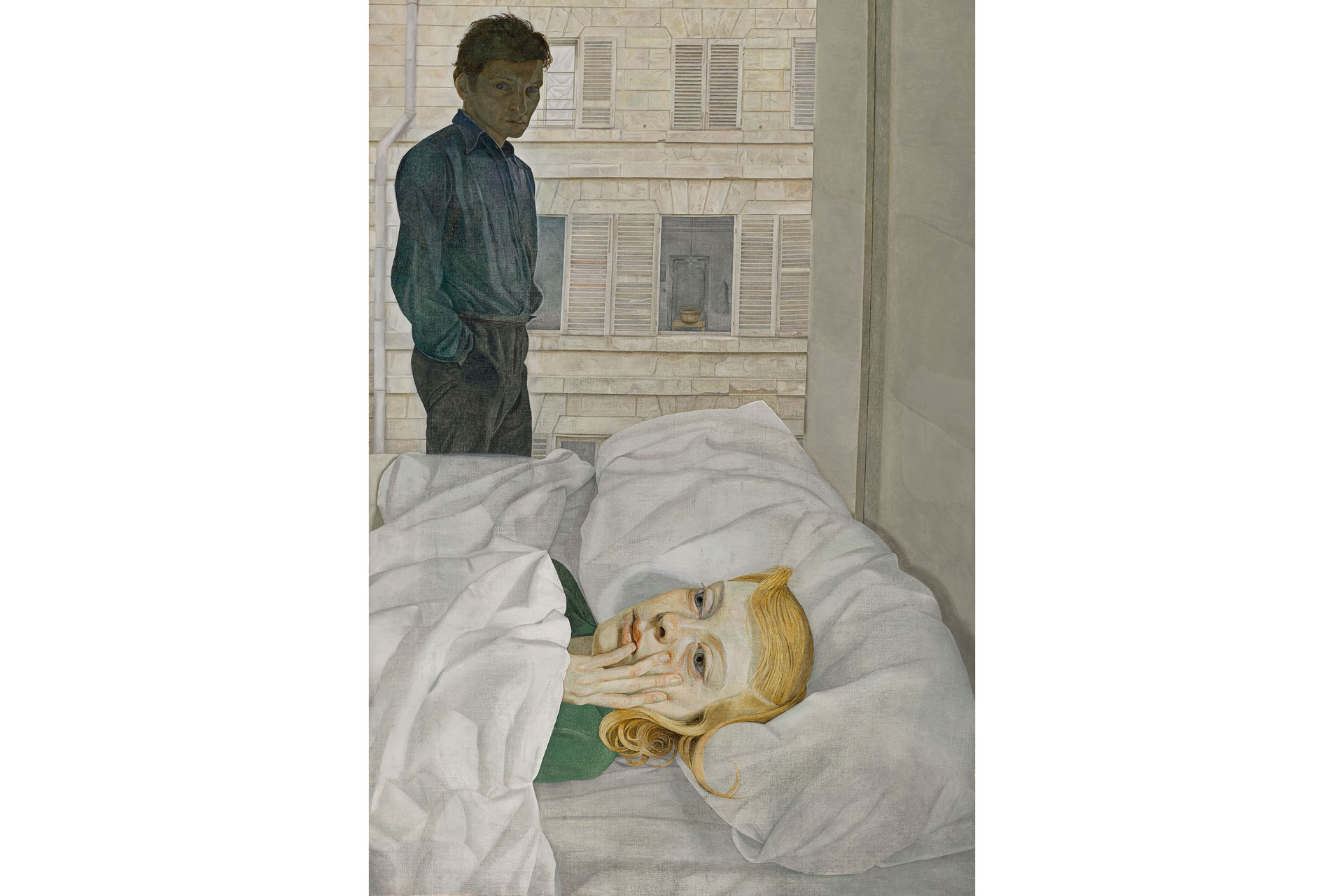

Lucian Freud, Hotel Bedroom, 1954. Oil on canvas. 91.1 x 61 cm. The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, Canada © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images / photo The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, Canada

By the mid-1940s, Freud had left his naïve phase behind and some more interesting works appeared, such as ‘Woman with a Tulip ‘ (Cat 7) and ‘Girl with Roses’ (Cat 9), both from 1947. These works are well drawn with a linear quality that is particularly evident in the two self-portraits of 1948 (Cat 13 and 14). There is little impasto, or contrast in the skin tones, but the paintings are precise and memorable. The woman portrayed are his girlfriends and this was the start of his habit of drawing and painting the women in his life. It is not certain whether they were his lovers who became his models, or his models who became his lovers, but as Jack Woodford once wrote, ‘Few human beings are proof against the implied flattery of rapt attention’.

The catalogue lists his girlfriends through the 1940s and 1950s as Lorna Wishart, Pauline Tennant, Anne Dunn, Kitty Garman, and Caroline Blackwood, and paintings of most of these women feature in the exhibition. Portrait sittings sometimes required hundreds of hours, with breaks for food, conversation, conflict and sex. Freud described his method as follows: ‘I work from the people that interest me and I care about.’

In ‘Girl with a White Dog ‘ (Cat 17) of 1951, a woman is seen, one breast exposed, sitting in a dressing gown while looking apprehensively at the viewer, a dog in her lap. This painting was an early acquisition by the Tate Gallery in 1952. In ‘Hotel Bedroom’ (Cat 21) of 1954, Freud depicts himself standing beside a window while a woman lies awake and clothed in a bed with just her head visible. She looks pensive and the mood feels like the end of a love affair. About this painting, Freud said, ‘Hotel Bedroom is the last painting where I was sitting down; when I stood up I never sat down again.’

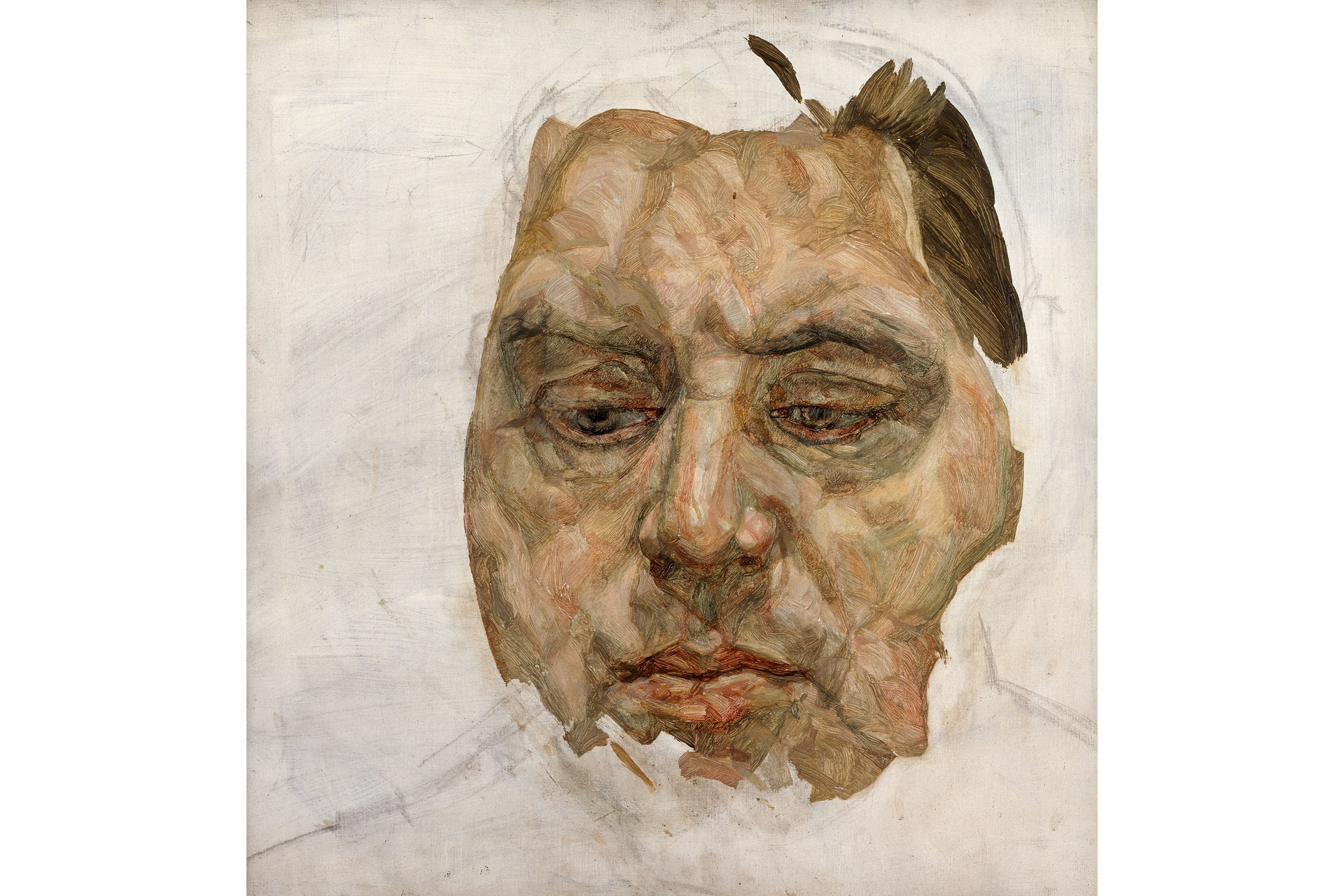

Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon (Unfinished), 1956-7. Oil and charcoal on canvas. 35.5 x 35.5 cm. Lent by Ananda Foundation N.V. © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Image

By the mid-1950s, Freud started to develop an interest in trying to master the depiction of flesh and this led to some of his most successful portraits, such as the famous unfinished (possibly deliberately so) depiction of his friend and fellow painter, Francis Bacon (Cat 25). By now, Freud could give a realistic treatment to flesh tones and his drawing was still sure. In many ways, this period was the height of his achievement.

By the 1960s, Freud’s life was at its most chaotic. This period is described in the exhibition catalogue as ‘one of painting, gambling and living off his wits, in a decade of multiple partners and fathering several children by different women’. The works become more painterly and the drawing less sure. We have already seen that Freud was an excellent draftsman, but he seemed to lose interest other than when he was actually doing a drawing, such as those of his mother (Cat 44 and 45), and he became more focused solely on expressing himself in paint.

The treatment of his sitters’ extremities, such as hands and feet, deteriorates from this point onwards. In addition, the enormous number of sittings he demanded of his models meant that often the lighting in the portraits is confused. Different times of day meant the shadows were in different places and Freud’s style, based on intense observation, often failed to reconcile these lighting difficulties.

Lucian Freud, Large Interior W9, 1973. Oil on canvas. 91.4 x 91 cm. The Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees / Bridgeman Images

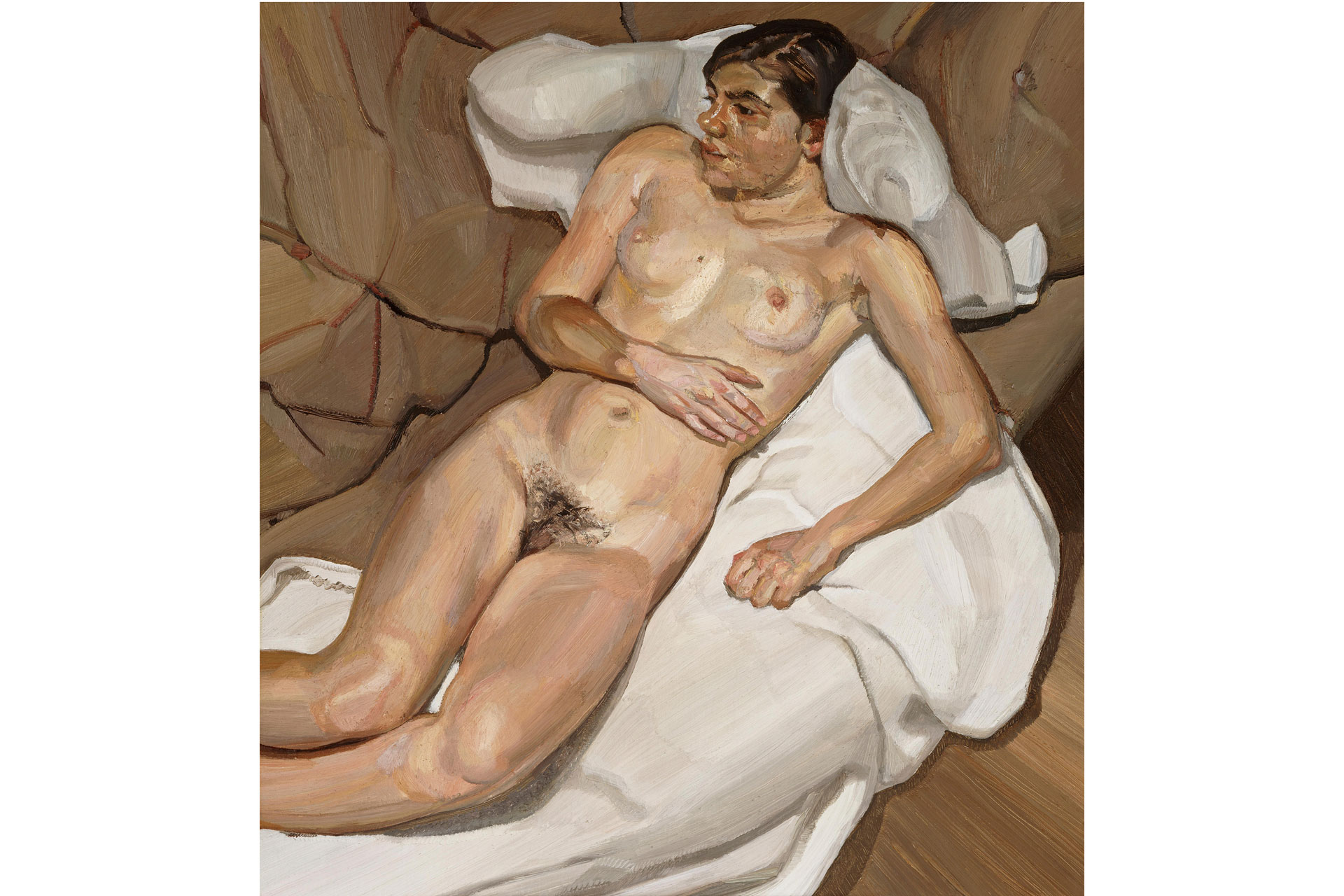

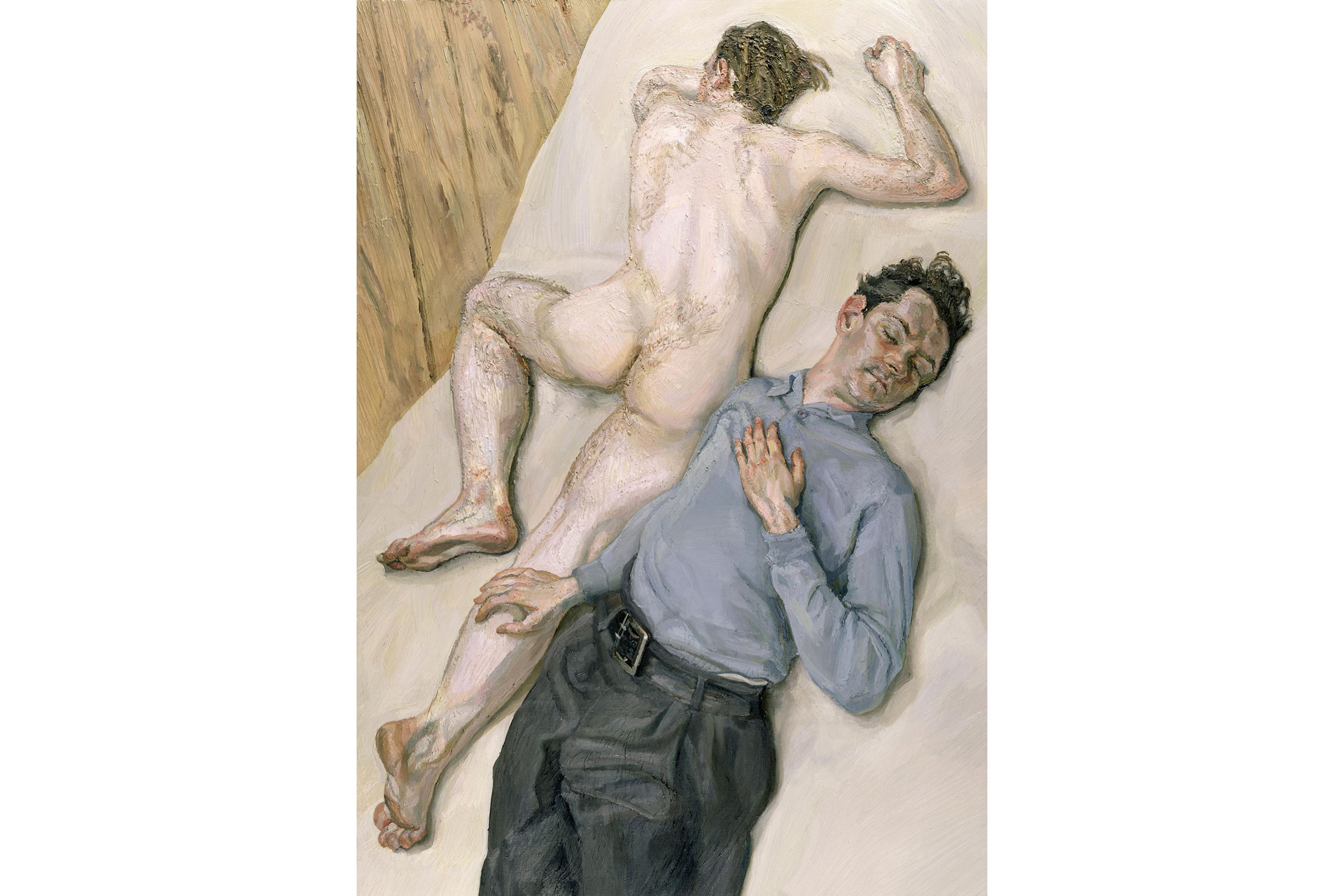

The artist becomes interested in double portraits, trying to show the relationship between two sitters. Where he had to paint the subjects at separate sittings – such as in his ‘Large Interior ‘ (Cat 31), where his mother sits in the foreground and his girlfriend lies down behind – the figures feel detached from each other, giving the work an uneasy feel. ‘Two Men’ (Cat 32), where one nude man, and one clothed, lie sleeping next to each other, feels more successful. That the clothed man reaches out to touch the leg of the naked man is an obvious gesture, but it successfully provides a connection and an intimacy that is lacking in his female portraits.

Lucian Freud, Large Interior W9, 1973. Oil on canvas. 91.4 x 91 cm. The Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees / Bridgeman Images

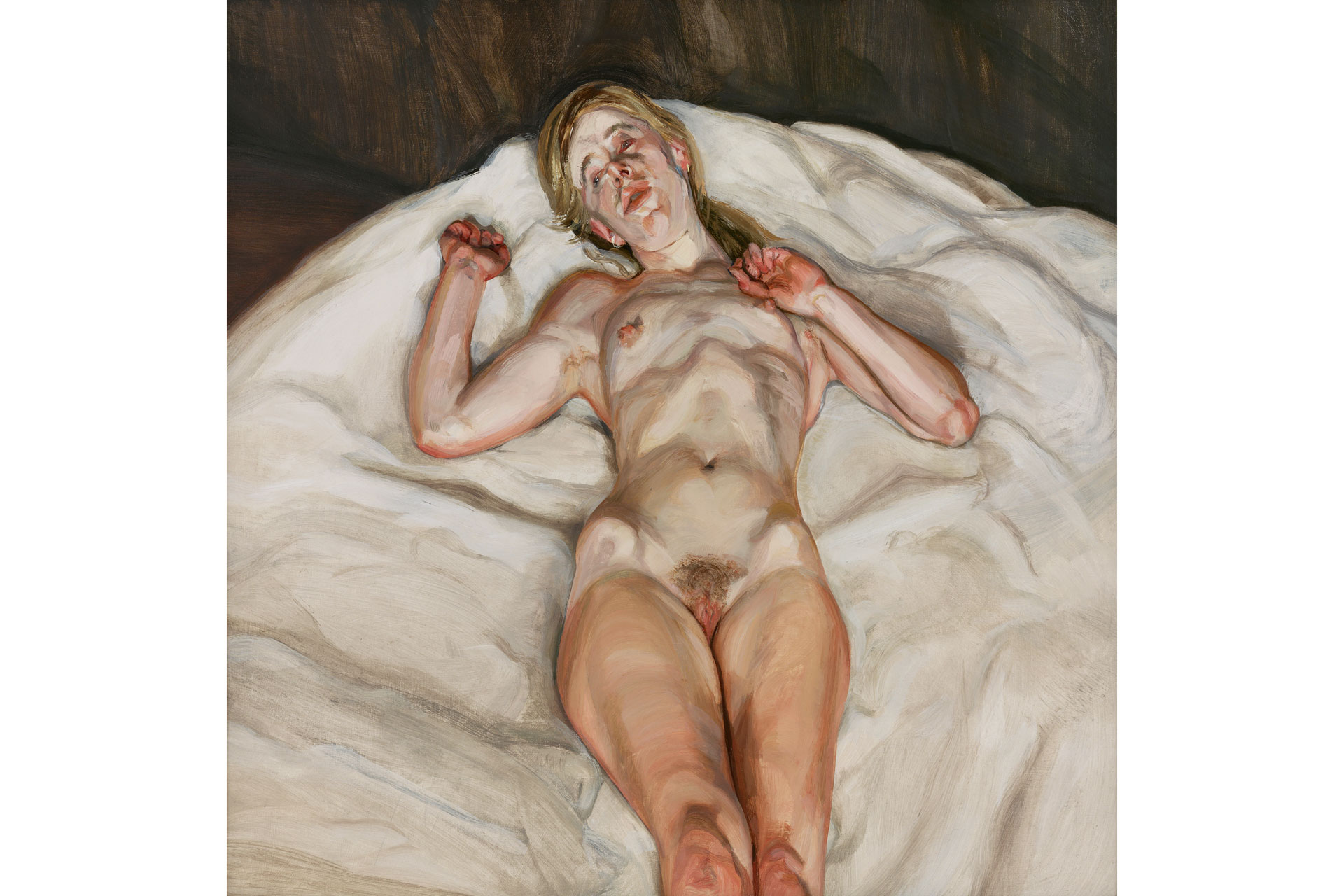

It was in the mid-1960s that Freud started working on the nudes for which he is perhaps best known. The catalogue states that the ‘Naked Girl’ (Cat 65) of 1966, reputedly of Penelope Cuthbertson, was the first of these uncompromising nudes. The girl is depicted from her knees upwards, awake, and just lying there. It is sexual but there is nothing sensual or erotic about it or any of the other women depicted nude. Freud focuses the viewer on the genitalia of his sitters as the centre of the composition, and his admirers refer to these paintings as realistic and uncompromising, but this writer recoils from their clinical and cruel aura. The artist Tracey Emin articulates this dichotomy by acknowledging the nudes are interesting while also observing that ‘some of Lucian’s, they’re really horrible to look at: the flesh and the fannies and the stomachs and the skin, it’s really not very nice.’

Lucian Freud, Bella, 1982-3. Oil on canvas. 61 x 55 cm. Private collection © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022/Bridgeman Images

The women are most often depicted either asleep or, if awake, with an uneasy expression. One senses the artist had some anger towards women in the way he tried to portray them in such a basic, pared-down fashion. It is as if women are reduced to their most basic function. Some of this may be attributable to Freud’s overbearing mother about whom he said, ‘She was so affectionately, insistently maternal… it made me feel sick.’ Freud’s friend, the artist Frank Auerbach said, ‘her [Freud’s mother] unyielding devotion rendered it impossible for him to have such an unconditional relationship with any other woman.’

In Kenneth Clark’s 1959 book The Nude (A Study in Ideal Form), an epic historical analysis of the depiction of the human body, Clark opposed the naked as ‘huddled and defenceless’, with the nude as ‘balanced, prosperous and confident… the body reformed’. When describing Francois Boucher’s ‘Portrait of Miss O’Murphy’, Clark said: ‘Freshness of desire has seldom been more delicately expressed than by her round limbs, as they sprawl with undisguised satisfaction on the silken cushions of her sofa.’ Clark celebrated myth and wonder in the depiction of the nude, whereas Freud seems to have been determined to never deviate from the merely naked. The exhibition catalogue says as much: ‘Freud preferred to talk of figures who were naked rather than nude.’

Interestingly, when the artist paints a nude of his daughter, ‘Bella ‘ (Cat 36), in 1982, he slightly pares back the shock element. Yes, she is nude, but the composition is a little more forgiving, less full frontal, and the anger is missing. His portraits of men, mainly gay, have a very different atmosphere, as if the lack of sexual tension allowed him to be more cheerful, playful and relaxed. When Leigh Bowery once asked Freud why so many of his male portraits were of gay men, Freud said he was drawn ‘to queers because of their courage’.

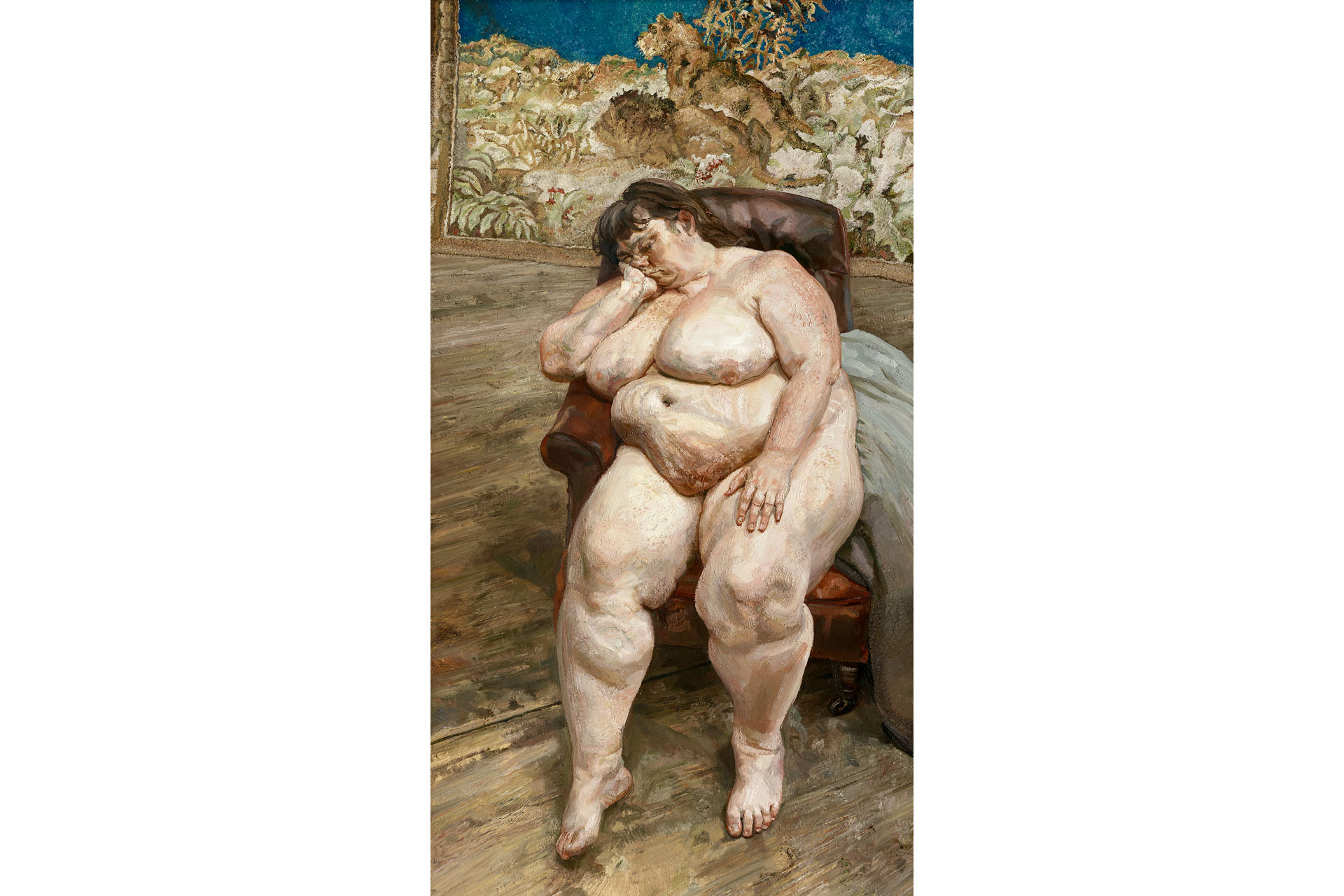

Once Freud started on this path, it led him to a series of nudes of the performance artist Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley. Sue Tilley (more normally referred to by her job description, ‘Benefits Supervisor’) is depicted in ‘Sleeping by the Lion Carpet’ (Cat 72) of 1996. She seems to have been chosen by Freud for her vast size, and these paintings feel exploitative and monstrous. Richard Cork described this as: ‘Freud demands that we accept the right of women like the supervisor to be studied with as much care, and as on a grand scale, as more congenitally proportionate bodies.’ But he also seems conflicted, mentioning ‘a sofa bucking under her weight’ and that the ‘slack folds of pale fat’ mean she is a ‘woman burdened by bodily excesses’.

Lucian Freud, Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, 1996. Oil on canvas. 228 x 121 cm. Private collection © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images

In these later works, Freud’s technical ability seems to suffer, particularly in clumpy hands and feet, and he introduces a strange unsatisfying scratchy surface to his flesh tones, possibly from the introduction of sand in the paint. Perhaps he realised that the mundanity of his portraits meant that he had to provide a shock factor to be seen as original and uncompromising, and in order to enhance his status and the value of his output. He was correct in that, if he could focus the audience on the subject matter, such as the acres of flesh in the paintings of Sue Tilley, they wouldn’t notice the failings in the execution.

In the portrait of the Queen (Cat 56) of 2000, if you block out the crown, hair, earrings and pearls, it would be hard to know this is the Queen. It looks more like a man wrinkling his nose at a bad smell. God only knows what the Queen must have thought of it.

Lucian Freud, Two Men, 1987-8. Oil on canvas. 106.7 x 75 cm. National Galleries of Scotland. Purchased 1988 © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images / photo NGS

The catalogue is keen to discuss the artist’s relevance to the greatest of Old Masters whenever it gets the chance. Comparisons are made to Watteau, Titian, Durer, Van Eyck, and so on. Freud himself spent considerable time studying the Old Masters and trying to learn from them. He had a special pass that allowed him into the National Gallery at any time of day or night, and he said, ‘I go to the National Gallery rather like going to a doctor for help’. However, to this writer, his name cannot be spoken in the same sentence as these artists. Unlike exhibitions in the concrete basement of the Sainsbury Wing, this exhibition suffers because, to get there, you have to walk through the permanent Renaissance collection of the National Gallery, which takes you past the likes of Titian, Bellini, Holbein and Del Sarto. As Bernard Berenson said, great art is ‘life-enhancing’ so, by the time you have got to the exhibition, your mood has been elevated and you walk into the show with great anticipation. You rapidly come back down to earth.

The commercial Freud freight train is unlikely to derail anytime soon, as too much has been invested in his oeuvre. Indeed, ‘Large Interior, W11 (after Watteau)’ (Cat 59) from Paul Allen’s collection has just sold for US$86.3m, a new auction record for the artist. I don’t deny Freud has his moments: the early linear works are tight and original, the mid-1950s portraiture, such as the unfinished study of Francis Bacon are accomplished, and the mid-1980’s portraits of business tycoons such as Baron Thyssen (Cat 50) and Lord Rothschild (Cat 50) capture a good likeness. But his nudes feel pedestrian, exploitive and reliant on their shock value. He is a good artist, but the man himself is more interesting than the art. The only true art critic is the passage of time, and I suspect time will not be kind to Freud’s reputation.

Lucian Freud, ‘New Perspectives’ can be seen at the National Gallery until 22 January 2023. nationalgallery.org.uk

Featured Image: Lucian Freud, The Refugees, 1940-1 Ink on paper 30.7 x 25.6 cm Private collection © The Lucian Freud Archive. All Rights Reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images