What To Expect From Marc Quinn’s Light Into Life Exhibition At Kew Gardens

By

10 months ago

An anarchist naturalist

A visit to Kew Gardens is always an attractive proposition, but ‘Quinn at Kew’ adds a dual draw, says Wendyrosie Scott. Here’s everything you need to know about the Light Into Life exhibition.

Review: Light Into Life At Kew Gardens

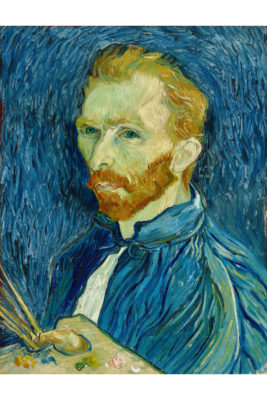

Held by Desire (The Dimensions of Freedom) 2017-2018 (c) Marc Quinn Studio. Ph Robert Berg

There are just three weeks left to visit the much-hyped exhibition by long-time artist Marc Quinn – once assigned the moniker YBA (Young British Artists, a loosely connected group who came onto the art scene in the 1980s and 90’s defined by their entrepreneurial nous and shock art tactics). Quinn became known for his ‘blood head’, which used his own blood to create an eerie and magnetic apparition whose apparent solidity was all the more perplexing and haunting. At his Kew exhibition, viewers are once again treated to influences which draw upon the more beatific as well as scientific. With sculptures strategically shared around the site indoors and out, many dwell in harmony with their surroundings, yet there is an intriguing disquiet. Quinn brings ‘cutting edge’ to Kew.

The world-famous institution is, it seems, on a mission to merge the magical properties and potent potential that can come from art and botany conversing and converging. It is a fashionable pairing on the rise in many realms globally and is set to continue. (Personally, as an area of specialist interest, I’ve been quietly observing its prominence, which was further accelerated during the pandemic). With the current political, environmental and financial uncertainty, this evolving ecological entity and collaborative creative medium holds an immense ability to communicate what is not always comprehensible. Quinn pays tribute to the vast knowledge at Kew as well as its rare, beautiful, medicinal and magnificent plant specimens, whether actual and factual or artistic renderings. Exploring the relationship between people and plants, this is a unique collaboration between the artist and Kew’s scientists.

DNA Garden

Given the crowds encountered during the weekend (some of whom had travelled many miles to see ‘the Quinns’) there were, at times, small groups gathered at the sculptures, with many taking selfies (bah humbug) which was frustrating but also uplifting – possibly signifying that art is being taken more seriously, and yet regarded less as a lofty discipline. It was nevertheless an accessible and enjoyable spectacle, and there was a palpable curiosity at every sculpture.

The show is mostly a great success, as is the ethos behind it. The smaller shiny sculptures – seemingly Quinn’s response to the pressed flowers held at Kew, and which reflect the surrounding woodland – were deliberately flat both as a construct and interpretation. There were pockets of work I didn’t manage to see which sounded intriguing (particularly the vase and illustrations), all confronting the ease at which animal blood can be purchased, and, in the case of horticultural usage, can give life to another in the natural world. This area is worth platforming provocatively but perhaps some generic text informing on the rise in animal cruelty could have helped, as some may not make the connection. It’s not about being didactic but utilising this fabulous opportunity to assist a cause. Clearly, as an artist, to be given this opportunity in a globally revered realm is ego-inducing.

Burning Desire by Marc Quinn at Kew Gardens. (c) RBG Kew.

Yet it is also a chance to be inspired. And while the monumental and gargantuan bonsai tree sculptures were awesome, they were somewhat disturbingly indulgent. Of course they represent humankind’s manipulative and contradictory relationship with the natural world, where Quinn was keen to stress the consumption and commodification of the very thing we then ironically exploit at every opportunity. Entitled ‘Held by Desire’, the sculptures loomed large, positioned in the Temperate House, the world’s largest surviving Victorian glasshouse. The practice of growing miniature trees and shrubs (bonsai) means these plants are kept at a consistently small size through careful pruning, purely for the aesthetic. Quinn aims to ‘free the trees’ and renders them in five-metre bronze sculptures, allowing them to flourish and ‘grow’ to a gargantuan height. It evokes mixed feelings.

Much of the work is outdoors. The peacock-like steel sculptures pay homage to ferns, yet, despite their fixed stance, they have a fluidity reminiscent of ‘train rattling’, the natural behaviour carried out to attract a peahen, when the peacock is ‘strutting his stuff’. Sitting in such green and pleasant pastures, a stand-out stellar Quinn sculpture created a sense of unease with its unnatural materiality. The exaggerated and overly red ornamental orchid is super-sized and possesses a perverse and powerful appeal. I read later it is a nod to the medicinal and potent properties of the opium poppy. It is a bold approach – and who doesn’t enjoy a bit of anarchic controversy? Surely that’s part of the artistry and artistic licence. Job done, Quinn.

The exhibition Light into Life by Marc Quinn ends on 29 September. For more information, visit kew.org