Art For Art’s Sake: Marc Steene Discusses His New Book – Interview

By

1 year ago

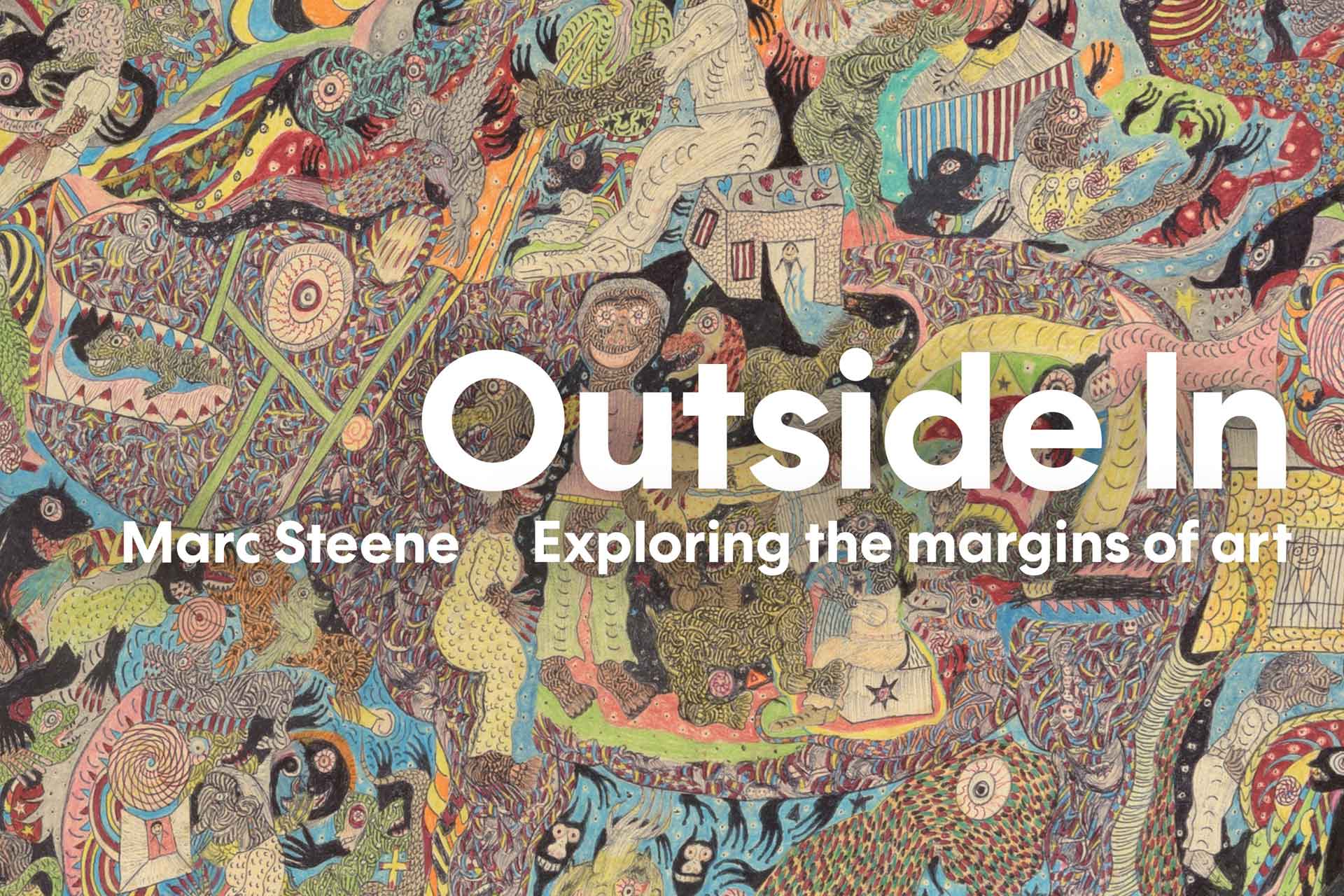

'Outside In: Exploring The Margins of Art' is available now

Marc Steene’s extraordinary book Outside In: Exploring The Margins of Art interweaves his own journey in setting up an award-winning arts charity with an exploration of the history of ‘outsider art‘. He tells us about the shocking moment that changed his life, why he struggles with the term ‘artist’ and what he would secretly like to hang on his walls.

Marc Steene Discusses His New Book, Outside In: Exploring The Margins Of Art – Interview

When and why did you first become interested in art?

My mother first introduced me to art, being Italian and proud of her culture and I was raised appreciating artists like Raphael, Michelangelo and Giotto. My earliest memories are of visiting my grandparents in Rome and witnessing first-hand the splendours of renaissance art. Partly inspired by my exposure to classical art, I started to draw in earnest when I was around 7 or 8 years old. It was my safe place, somewhere I could create and escape to when my life became difficult.

You had some considerable success as an art student and then turned your back on the traditional art world. Can you tell us why?

I found the commodifying of my work incredibly difficult; like a lot of the artists in my book, I created my art out of need. It was my means of self-development and personal discovery; it enabled me to express sometimes difficult emotions and to deal with them. When confronted by the art world and art market I found there was a distinct and brutal juncture, a place where what I had created was seen as a product, something to be sold, often for reasons far removed from its purpose and creation. It is a difficult trap that ensnares one far too quickly, especially as a young person, painting to live and pay your way in life. Instead of painting for yourself you are painting to sell, guided by the need of the market, by galleries and agents wanting what their customers will buy and not understanding the deeply personal associations that my work held for me. This impasse eventually made me unwell, and I turned my back on the art world and eventually, after a journey of self-discovery, found a wider set of creators who like me did not fit.

Having started to work as a volunteer in a day centre, you talk in the book about a pivotal experience involving the destruction of work by a group of artists which you had intended to exhibit. What happened and how did this affect you?

As part of my journey to find myself I started working at a day centre for adults with learning disabilities. I remember wanting to immerse myself in people, having been isolated for far too long in my studio. Kathy Pettet was the wonderful woman who ran the day centre; she is sadly no longer with us, but she played a large part in my life. She knew of my interest in art and organised a group of about eight adults for me to work with. I came expecting to teach them how to draw and paint, but using the most basic materials, poster paint, sugar paper and felt pens, they created paintings so unique and beautiful that they changed my life. Inspired by the work I organised an exhibition of their work, keen to share the work more widely, knowing that it was exceptional and needed to be shared. On asking for the work back from the staff at the day centre I was told that it was no longer available and had in fact been turned into papier-mâché for the artists to make into pots that would soon end up in the bin – their art solely a means of filling time and not seen as having any value or that they as artists had the right to create and be respected as artists.

The artists I met during my time at the day centre crystalised my own experiences and thoughts into a wider realisation of the unfairness and disparity in the art world.

Rakibul Chowdhury, Ophelia after a painting by Millais, 60 x 40 c, acrylic and watercolour on paper. Courtesy of the Outside In collection.

How did the formation of Outside In come about, and what was its mission?

The charity grew out of these experiences in that day centre and officially came into being as part of the Community Programme at Pallant House Gallery in 2006, when I was Executive Director there. Its mission was to create a fairer art world where the work of traditionally excluded artists could be exhibited and celebrated, and to create opportunities and provide training to diversify roles within the arts – to change the art world for good!

Flash-forward to today and you are now representing over 4000 artists and exhibiting their work at venues across the UK, including Sotheby’s. How does this feel and what sort of benefits are you able to provide the artists under Outside In’s umbrella?

Looking back over the 17 years since Outside In has been in existence I feel as if a lot has been achieved, many lives changed for the better, and that the art world has been challenged to engage with and appreciate a wider set of creators than it would traditionally. But it feels like this is only the start of what will be a long and ongoing journey. There is still so much to do to enable galleries and museums to be truly representative of their local communities, and so much to change for the artworld to become accessible and relevant to all who create.

I feel that the major benefit that Outside In provides artists is validation. From the first step when they share their work and it becomes visible on our website, to the first time they talk about their work, to the first time their work is hung in a gallery, to the new skills they learn and roles they take up in the art world. We provide pastoral care and support through our artist development programme, the opportunity to exhibit their work and undertake commission and residencies through our exhibition programme and the chance to learn new skills and gain employment through our training programme.

Who is eligible to become an Outside In artist and what does it entail?

Any artists who fit the criteria of the charity – those encountering significant barriers due to health, disability, social circumstance or isolation and who need our support. The reasons for joining vary enormously and we offer support to a wide variety of people including neurodivergent artists, artists struggling with homelessness, addiction or mental health issues, disabled artists, refugees, ex-military personnel with PTSD or former prisoners. It is quick, easy and free to join, set up an online gallery, find out about all the options available and start a journey with us. For those needing help to set up a gallery, photograph their work and write an artist’s statement, we offer support at our dedicated Artist Support Days.

Do you believe that everybody can be an artist? Aren’t some people more naturally talented than others or talented in other fields, like scientists or wordsmiths?

I have a problem with the term ‘artist’, as it holds so many connotations and is so easily used and misused – I prefer creators and creativity. I believe we are all creative and that creativity is one of the most important human characteristics; it underpins all our great achievements as a race, and it is what most marks us out and has enabled us to create great art, make scientific breakthroughs and understand the universe.

Talent or value as an artist is an anomaly; it all depends on who is doing the valuing. There is no one scale that can be agreed on that will show what is good and what is bad art or who is of talent and who not. We each have the capacity to judge and appreciate art, writing, dance, or any art form. The truth is that for far too long the judgement as to what is labelled as of worth or who is talented is done by those in power. In other words, those who have been educated or have had the opportunity to study, those with money and too often not the people making the work themselves. This can mean that the art world is more often talking to itself, using language and ways of thinking alien to a wider community of audiences and creators.

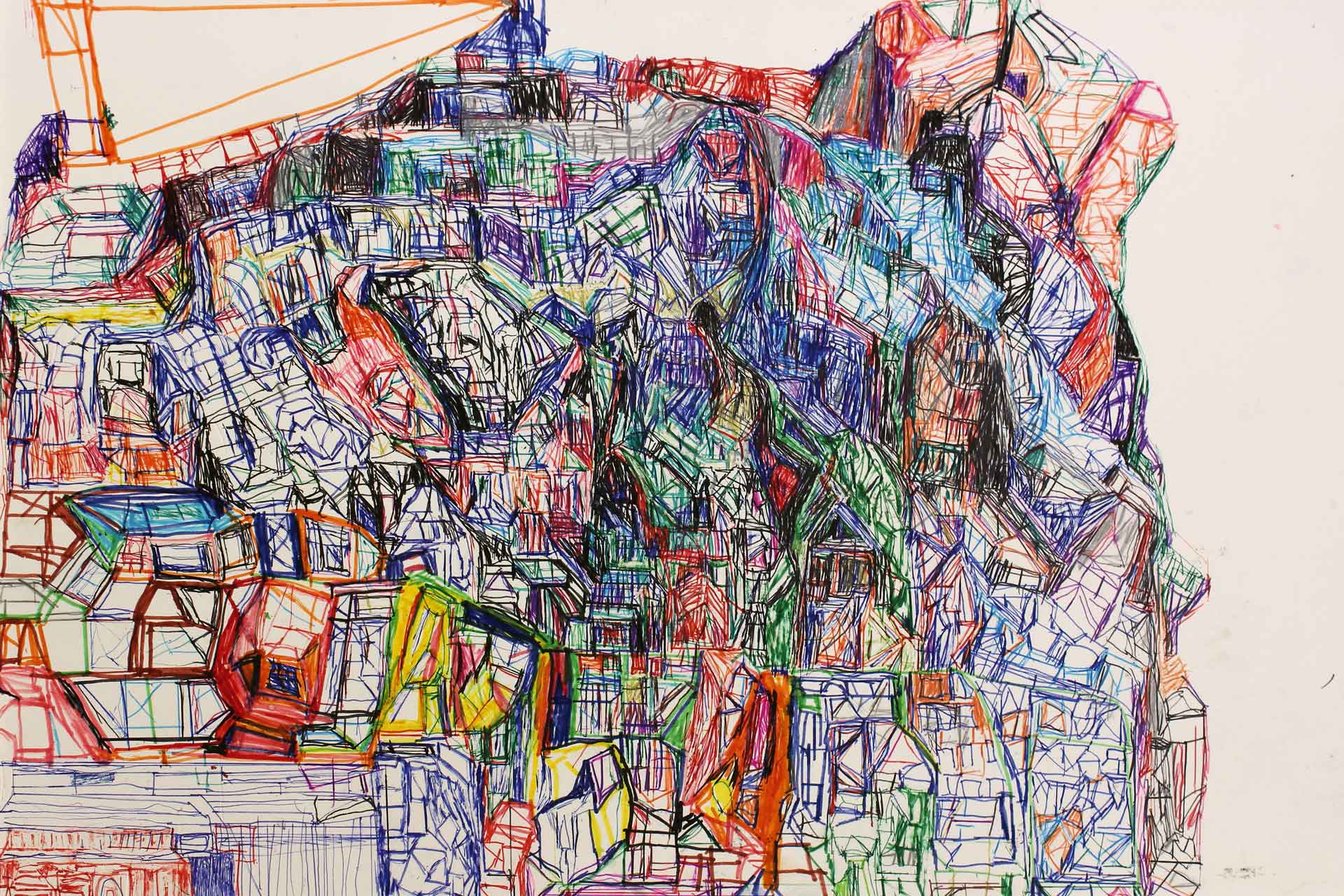

No. 44, Matthew Beadon, Untitled, 2016. Courtesy of the Outside In collection.

You draw many parallels and give examples of art benefitting people’s mental health and wellbeing. Can we all take lessons from this and what would you recommend?

Being creative is therapeutic, full stop. It does not matter what form your creativity takes. it will make your life richer. Whether it is writing, doodling, painting, gardening, or dancing it will help you grow and develop as an individual, meaning that you will be happier and better able to function.

In your book, you focus on historic and contemporary work by artists outside the mainstream, often referred to as ‘outsider art’. How do you feel about this categorisation and do you think the language around it needs to change?

As you may have noticed from my book, the term ‘outsider art’ is much contested, it was originally coined by Roger Cardinal as the title of his 1972 book of the same name and as an anglicised version of Art Brut, itself a term created by the French artist Jean Dubuffet. In this context it is used as an art historical term, similar to other art movements, expressionism, impressionism etc. The problem is that were as the other movements are based on a commonality of style and approach to creating, ‘outsider art’ is a grouping together of artists whose only commonality is their difference or otherness. There is no one style or way of working in ‘outsider art’ it is an artistic ghetto for those who do not fit. More recently artists, some of them those we work with, have reclaimed the term, and proudly call themselves outsiders, they do this as they feel excluded from the artworld.

It is a much bigger question as to the dubious need and benefit of labelling art and artists. To me it seems an academic and art historical approach to understanding and explaining art and one developed by nineteenth-century academics, so far removed from the world we live in. It might be better to think of artists as individuals and that each has their own story and way of making, humanising art I feel would go a long way to making the art world more relevant in our time.

What do you think are the most important steps in terms of changing the art world to make it more inclusive? Have far away is this from happening – are there any signs of change?

Similarly to the point above, I think that respecting and treating people as individuals would go a long way to enabling real change. To be truly inclusive and accessible the art world needs to rethink the way it operates. There are a set of skills and characteristics that artists require to be able to navigate and succeed, the ability to talk about your work, the confidence to enter a gallery, the ability to use the internet or to be able to read and write. Having these skills will not mean that the person is an artist of worth but not having them means they will be invisible. There are signs of change, as a charity we work with a large number of art institutions doing amazing work, such as Action Space whose artist Nnena Khalu, featured in my book is doing amazing things and Project Artworks being shortlisted for the Turner Prize last year was amazing.

There are some incredible stories about artists and their work and experiences detailed in the book. Can you recap on a few that stand out for you?

As you say there are some incredible stories, some uplifting others not, I am most drawn to where an individual has used their creativity to deal with challenging circumstances. I think Drew Fox’s story is deeply moving, having had a near death experience he created cameras out of biscuit tins to attempt to create photographs of the experiences he had during that time. Wilhelm Werner is another who springs to mind, a victim of the Nazi regime and forcibly sterilised and euthanised, his playful drawings belie the awful experiences he was part of and seeking to express. There are others more playful such as Manuel Bonifacio an artist originally from Portugal whose work is full of charm and life, reflecting his earlier life and current interests.

You also talk about some extraordinary places in Europe to experience art outside the mainstream . Where would you recommend that interested readers should visit?

There are so many that it is hard to list, but anyone interested should definitely consider visiting the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, the Prinzhorn Collection in Heidelberg and Halle St. Pierre in Paris. As to environments I would suggest visiting Picassiette in Chartres, the Junker House in Lemgo, Germany and the Palais Ideal in Hauterives in France, a remarkable and exceptional structure by Ferdinand Cheval.

If you could own any artwork by any artist living or dead, what would it be?

That’s an unfair question as there are so many I love and do not want to seem to be defining my aesthetic by what I choose! But if I had to it would be an artist from Italy, given my mother’s influence and a painting by Titian, The Death of Actaeon, at the National Gallery.

What is next for you and for Outside In?

I’m pleased to report that it’s an extraordinarily busy time for us – it’s never been busier in fact! As well as the launch of this book, which I really hope will help to spread our message, we have the final leg of our national open exhibition, Humanity, now on at The Hove Museum of Creativity until 21 January 2024 with 80 extraordinary works by our artists on show. We have just announced a partnership with The New Art Gallery in Walsall who will be hosting our next National Open exhibition in 2025 and we are planning a solo show by the winner of our current National Open, Michelle Roberts at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill On Sea next year.

We are hosting Humanising the Arts, an international symposium in January at Fabrica Gallery in Brighton with speakers including Frances Christie of Sotheby’s and V&A East Curator Madeleine Haddon. We are also busy developing new regional hubs across the UK and launching Studio OI, our new commercial arm which will enable us to fundraise and sell more work by our artists. There’s still so much to achieve, and a long way to go!

Marc Steene’s book Outside In: Exploring The Margins Of Art is now available at £30 from outsidein.org.uk and all good bookshops.