Beyond the Beautiful: An In-Depth look into Miles Aldridge’s Art

Beneath its pop print colours and beautiful women, artist and photographer Miles Aldridge’s work goes more than skin deep, says Rosalyn Wikeley

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

Miles Aldridge has been invited to New York by Time magazine to shoot the cover for their ‘100 most influential people’ issue. Rosalyn Wikeley catches the British fashion photographer and artist while he’s taking a breather from the Big Apple’s ‘machine’…

Miles Aldridge

Miles, 53, is no stranger to the city. He played a pivotal role in the Nineties fashion scene, when ‘magazines ruled the world and you could work every hour of every day’, photographing fashion story after fashion story, svelte models with wide smiles.

It was amid this noisy backdrop of clichéd beauty that Miles forged an artistic philosophy that would become his trademark as a photographer.

Further influences included his design wizard father Alan Aldridge, a Central Saint Martins homoerotic directive (more on this later) and a childlike veneration for the provocative storytellers of film and photography – Alfred Hitchcock, David Lynch, Frederico Fellini, Helmut Newton, Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. Miles’ bright, erotically charged photography aligns itself more with film than photography’s traditional role of documentation.

His distinctly cinematic style seeks to ‘suspend disbelief and transport you to a world where things are more interesting, more exciting, more beautiful’.

In 2009 his work was showcased in Weird Beauty at the International Center for Photography in New York and in 2013 I Only Want You To Love Me at Somerset House was the largest exhibition of Miles’ work to date.

His works are also in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria & Albert Museum in the UK.

READ: How to Collect Photographs

‘A psychedelic, pop print world’

From lip-stained cigarettes aggressively sizzled into bright orange egg yolks to sexually charged, yet somewhat dazed beauties, sprawled among smashed plates, Miles has created a psychedelic, pop print world, bound into single shots. An avid disciple of Hitchcock, he is infatuated by the dual dynamic of attraction and repulsion.

This ease with beauty and colour can be traced back to the bright orange pop-art rooms of Miles’ 1960s childhood home in London. His father literally traded in the stuff as a noted psychedelic designer and close family friends included Eric Clapton and John Lennon. Striking beauty was the norm.

Miles’ sister, Saffron, was a model in Paris, later becoming the face of Ralph Lauren, while half-sisters Lily and Ruby have walked runways and graced billboards the world over. But Miles is quick to dismiss that such connections guaranteed him a seat at the table. Alan Aldridge’s shoes were tough ones to fill.

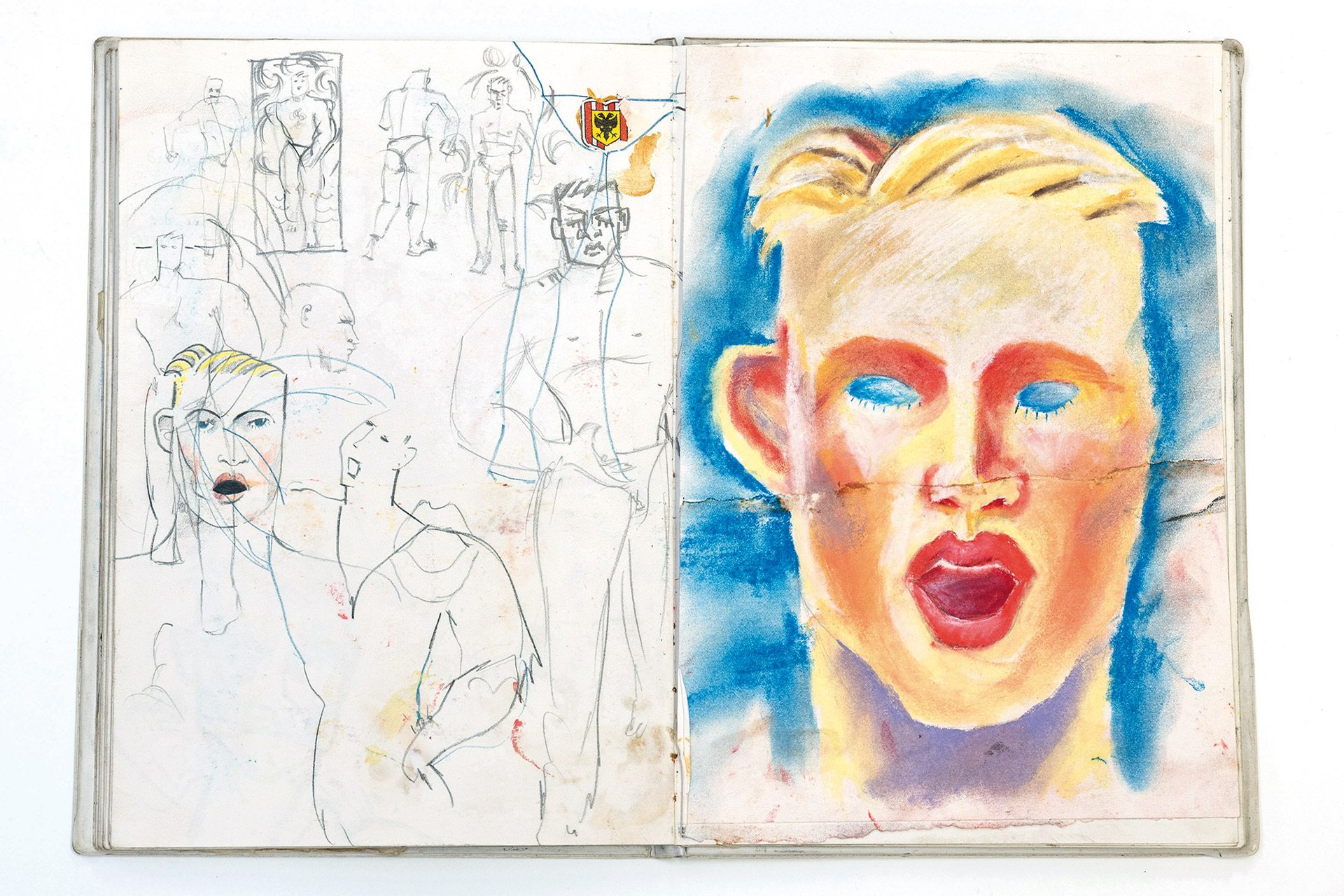

While first pursuing a career in illustration in the 1980s, Miles found his work routinely eclipsed by his father’s reputation. ‘I wanted to show them my drawings and photographs but all these art directors had such huge respect for my father that it was actually quite difficult.’

It wasn’t until Miles left Central Saint Martins that he started to flex his directing muscle. He moved out from his father’s shadow, still holding onto those early lessons in illustration and colour, which equipped him for his later career in ‘photo-fiction’.

READ: How to Take Better Landscape Photographs

Homoerotic influence

The homoerotic art of Miles’ Central Saint Martins illustration course was a major influence on him. ‘All my tutors were gay, and this had the effect of bringing my attention to a lot of gay artists, like Hockney. I’m not gay, but these drawings and paintings did influence me.’ As did the homoerotic photographs in Bruce Weber’s O Rio de Janeiro book and Richard Avedon’s powerful portraiture series In the American West.

Miles never chased photography, it ambushed him during a stint in the early ’90s making pop videos. He recalls shooting a video for The Verve, cross dressing lead singer Richard Ashcroft and his own girlfriend in his Bethnal Green council flat. ‘Richard had a bath in my flat then we started shooting… this wouldn’t happen nowadays.’

Miles helped this same girlfriend, an aspiring model, to shoot her portfolio on Hampstead Heath. A Vogue casting later and the model wasn’t hired but Miles was, and with it, pulled headfirst into a tsunami of ’90s commercialism, suddenly finding himself in New York with an agent. ‘I bluffed my way through it… God, it happened so fast.’

‘Stupid dumb pictures’

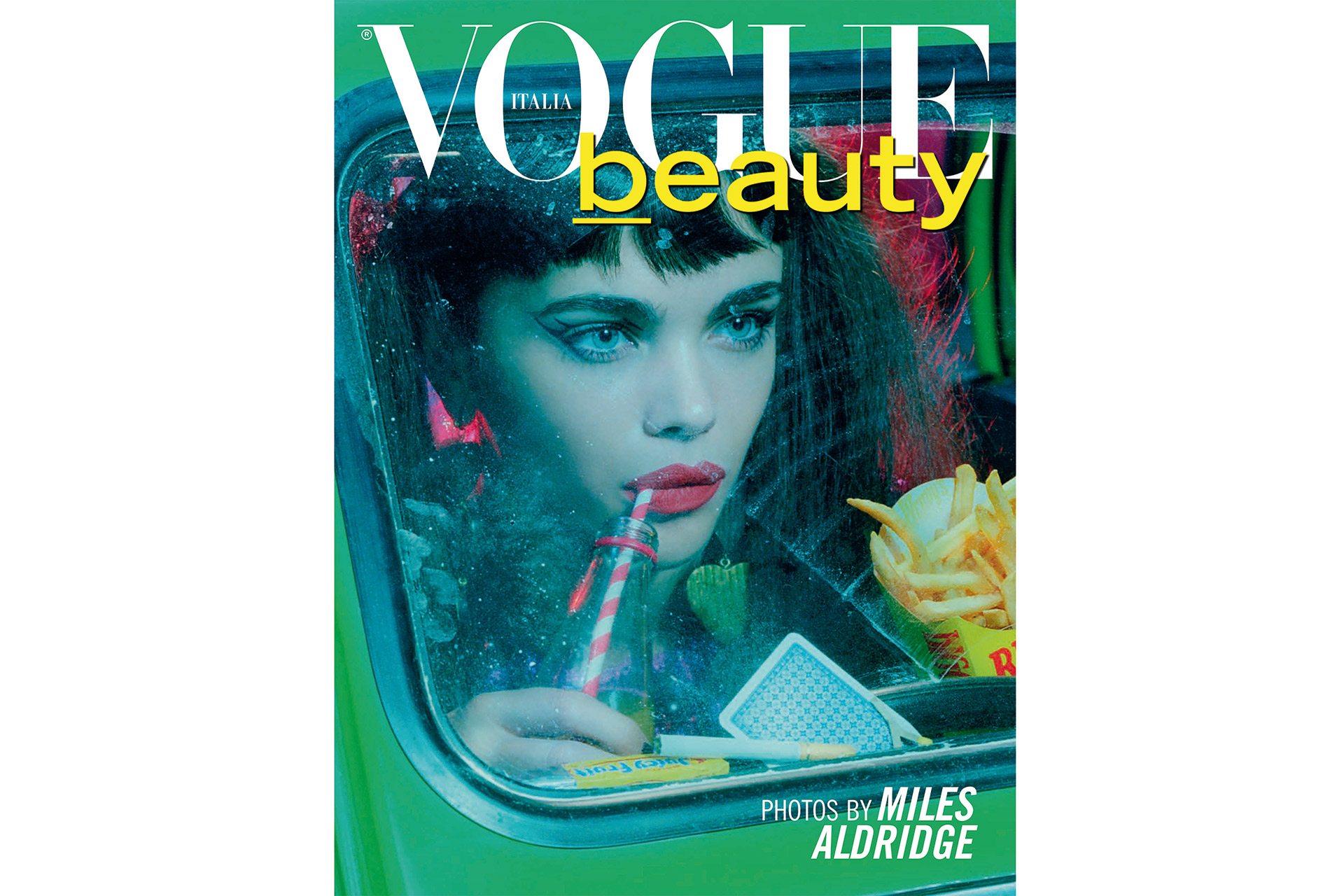

He found his forte photographing women and models: ‘I connected with them like a director.’ Miles was soon churning out front covers for American Vogue, Numéro, the New York Times and The New Yorker. But he tired of the ‘inane grinning and pictures of pretty girls’. Moreover he lamented his lack of vision, shown by his heroes – David Lynch, Egon Schiele, Benjamin Britten – ‘So,’ he asked himself, ‘why the hell make these stupid dumb pictures?’

Miles picked up his pen, dusted off his illustrator storyboard and paired it with his experience of directing music videos. ‘It’s not about the girl, it’s the fact she’s in a story and we – the audience – root for her to win… I’d create scenarios and drawings and take them to studios.’

Encouragement came thick and fast from photographers such as David LaChapelle. Italian Vogue’s Franca Sozzani saw Miles’ potential to assist her mission of ‘visual stories’, conquering the magazine’s Italian language barrier to increase its global appeal. There would be less work as his offering became more limited, but his creative energy had been stirred. Miles now had a message worth communicating.

The real point of art

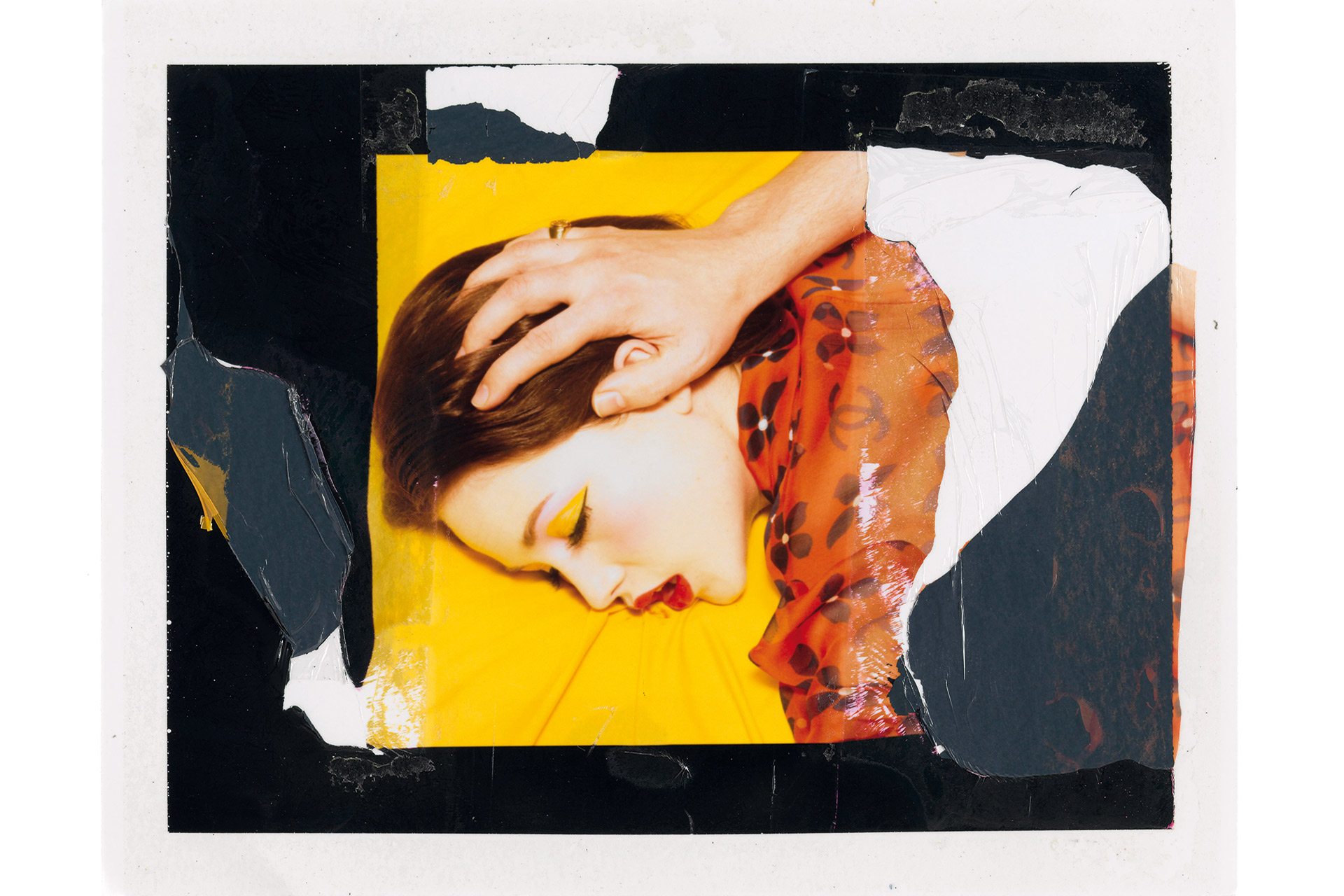

As an ongoing enquiry, Miles took his camera to beauty as a concept, studying it to reveal the pain that lies beneath. He saw his photography as a way to subtly and perversely expose these cracks. ‘It seemed that the most beautiful people I knew were some of the unhappiest.’ Splashes of loud colour were used to lure in an audience that was averse to these ‘truths’, unwittingly trespassing into private territory. Miles convinces me this is the real point of art, where created images are difficult to read, yet ‘potent in their ability to make you question things’.

His preference for nuance is surprising, given the pop-art lustre of his images. This closely emulates a Hitchcockian knack for exposing weakness, lifting truths and base desires hidden behind a screen of morality. Miles cites the shower scene from Psycho (1960). As Janet Leigh is murdered in a flash of blades, a male audience is simultaneously repulsed and pulled in by her naked body. Similarly, Miles relishes the thought that the owners of his paintings claim they make them smile, ‘I like that because even though there’s darkness to the work, it’s lubricated by humour.’

With New York and its factory fashion photography behind him, Miles took refuge in Highgate. He escapes every morning with a swim on Hampstead Heath. ‘It gives me a moment to be alone, swimming through the icy water’. Perhaps London best reflects Miles’ photography: vast and colourful, awash with theatre, ‘old fashioned but regenerating’. It is the only city where he feels at peace and ‘can just get things done’.

Appeal / repulse

He has just finished a project with Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, best-known for his satirical sculptures, especially La Nona Ora. The new piece will be unveiled at Photo London this month. They share a fascination with the appeal-repulse tug and decided to collaborate, cooking up an idea of a fashion scene with no fashion – think nude models interacting with Maurizio’s famous Hitler or his Pope.

The much-anticipated collaboration is symbolic for Miles. It marks a departure from editorial magazines. For him, the internet’s irony lies in its democratic promise; it has in fact tightened control over what content ‘works’ for magazines and what doesn’t, enslaved by instant gratification, rarely wrestling the status quo in fear of risking ‘likes’. This colourful photographer is embarking on a new direction, throwing his energy into galleries and artists, where the freedom and appetite for provocative images persists.

For Miles Aldridge’s prints, visit Lyndsey Ingram’s Gallery.