Good Reads: The C&TH Reading List

Take a look at these books that are top of our reading list...

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

The Reading List

This is your monthly list of the newest books to curl up with, whether by the fire in winter or on the beach come summer. Richard Hopton’s done the hard work for you of rifling through each month’s newest releases, bringing you the best reads that will accompany you on many a journey, sleepless night and cosy Sunday…

Why not challenge yourself to read one a week?

Brother

David Chariandy

This is a story of loss, grief and thwarted opportunity. Set in a run-down quarter of Toronto, it recounts the lives of a family of Trinidadian immigrants, a mother and her two sons. It is a moving tale of the tribulations facing immigrant communities, especially the ever-present racial prejudice, expressed both casually and violently. It has much to say about the shabby way in which western societies treat immigrants but also about the ties of love and duty that bind families, and the sacrifices parents make to better their children. Bloomsbury, £14.99

The Necessary Angel

C.K. Stead

Max Jackson is a New Zealander who lives in Paris and lectures at the Sorbonne. The Necessary Angel tells the story of his tangled relationships with three women: his estranged wife, a younger academic colleague and an English student. The novel reaches a climax which is surprising and unusual but apt. It is an enjoyable book, worldly and detached in tone, ruminative and amused, sophisticated without being pretentious. Stead captures the essence of Paris, its certainties and its contradictions, while simultaneously invoking the power of literature to alter and direct lives. Allen & Unwin, £15.99

The Only Story

Julian Barnes

Julian Barnes’ latest novel is a thoroughly rewarding book – a compassionate, touching and funny account of a lengthy relationship between a young man, Paul, and a much older, married woman. Late in life, Paul reconstructs the story from memory, at the mercy of the tricks, gaps and elisions of time. As the story progresses, the tone darkens as Paul’s youthful optimism evaporates. It is a novel about love, alcoholism, loss, disintegration, memory and the passage of time. A profound book, it compels one to think about one’s own life. Jonathan Cape, £16.99

Turning For Home

Barney Norris

This is Barney Norris’s second novel; his first, Five Rivers Met on a Wooded Plain, won a Betty Trask award. Turning for Home, set over one weekend in a rambling house in the English countryside, is a moving and subtle portrait of Kate, a damaged, vulnerable, anorexic young woman, and her grandfather, Robert. As the weekend progresses and the rest of the family arrive to celebrate his 80th birthday, Kate’s story and Robert’s career in British intelligence in Northern Ireland reveal themselves. This is an entertaining and clever novel about family, love and loyalty. Doubleday, £14.99

Territory Of Light

Yuko Tsushim

(trans. by Geraldine Harcourt)

Yuko Tsushima, who died in 2016, was a much-garlanded Japanese writer whose novel tells the story of a young woman recently separated from her husband and infant daughter. The novel has an allusive, elliptical feel – perhaps the result of the fact that its 12 chapters were published serially over the course of a year in the late 1970s. Set in Tokyo, it charts the young woman’s struggles with the demands of divorce, work and parenthood. Dreams play an important part in the novel, contrasting the young woman’s ‘inner’ life to her everyday, ‘outer’ existence. Penguin, £9.99

Happiness

Aminatta Forna

Happiness is a richly variegated and enjoyable novel.

On one level it is about London and the extraordinary variety and contradictions of the city. Aminatta Forna brings to life the polyglot cultures which thrive cheek by jowl in London and takes us into surprising corners of the city, not least the nocturnal world of the urban fox. Both the principal protagonists are sympathetic characters who have become, for different reasons, cut off from their roots. Jean, an American naturalist who studies urban wildlife, is forging a new life in London following her divorce. Attila is a Ghanaian psychiatrist who has spent many years travelling the world, flitting from one disaster zone to another, helping the survivors come to terms with their experiences. He is a citizen of everywhere and nowhere; he feels comfortable in many places but at home in none of them. Both have lived lives in which work has taken priority over family. It cost Jean her marriage and turned Attila’s wife into a grass widow, destined to die alone.

From the moment Attila and Jean bump into each other on Waterloo Bridge, their lives – and those of many other, disparate characters – become ineluctably entwined. Forna, whose novel The Memory of Love won the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize, writes understated, gliding, keenly observed prose. Her description of a care home’s smell as ‘sweet, stale air and nickel taint of medicine’ is perfect.

The novel, as the title suggests, is also about happiness. It is a hymn to the adaptability of the human spirit: many of the characters in the book have made new lives for themselves in London, far from home. This message is mirrored in the way in which foxes and coyotes have adapted so successfully to life in an urban environment. Change, even upheaval, can be a good thing; life is not, and cannot be, composed entirely of the bland and

the harmless. As Attila muses to himself at one point, ‘Was there no human experience that did not merit treatment now?’ Bloomsbury, £16.99

The Killing of Butterfly Joe

Rhidian Brook

Llewellyn Jones is a directionless young Welshman who falls in with the Bosco family and sets off across America with them selling butterflies. This rollicking, entertaining road novel is as much about make-believe and truth, loyalty and friendship as about the agonies of cold calling: ‘every sale you attempt contains the possibility of failure, rejection and a kind of death’. The prose is a marathon of brilliantly sustained folksiness and linguistic invention, a riot of erudition, both faux and real. A triumph. Picador, £14.99

Anecdotal Evidence

Wendy Cope

Wendy Cope’s new collection is a gentle celebration of life’s joys as she takes stock at the age of 70. She recalls childhood homesickness, ruminates on her father’s volumes of Shakespeare and grins at the memory of watching the 1972 Olympics on TV in a haze of dope. There is much humour, too, as when she. contemplates the notion of an archbishop jogging: ‘There’s no reason at all why he shouldn’t keep fit./It’s commendable. You can’t help sneering a bit.’ Cope’s poems may be deceptively simple, shorn of literary flourish, but they succeed brilliantly. Faber & Faber, £10.99

Rosie: Scenes from a Vanished Life

Rose Tremain

Rosie is a clear-sighted memoir of the author Rose Tremain’s upbringing. Abandoned by her father at the age of ten and unloved by her selfish, bulimic mother, it was her nanny who provided the love that enabled Rose to survive her emotionally suppressed childhood. This memoir is exquisitely wrought, full of telling details recalled with astonishing freshness despite the passage of time. The book is studded with footnotes explaining how specific incidents from her life surfaced in her novels, an interesting insight into how an author draws on life in writing fiction. Chatto & Windus, £14.99

Modernists & Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney & The London Painters

Martin Gayford

Martin Gayford is The Spectator’s art critic whose latest book is the fruit of three decades of interviews with London’s leading painters. It embraces those mentioned in the title but also Auerbach, Bomberg, Hodgkin, Riley and many others. It offers a comprehensive account of their careers as well as tracing the stylistic development of the various schools between 1945 and 1970. The art historical weight of the book is leavened by anecdote. In the 1950s, for example, someone suggested that Francis Bacon should live in Switzerland to which the great man retorted: ‘All those fucking views’. Thames & Hudson, £24.95

How Britain Really Works

Stig Abell

Stig Abell, former editor of the Sun and now in charge of the Times Literary Supplement, has written a brisk, readable account of how our most important institutions work. He casts his eye over the economy, politics, the NHS, the military, the police, the justice system and the media. His views are left-leaning – tellingly, he defends political correctness despite the fact that it ‘limits free expression, and precludes honest debate’ – but in general he favours common sense over ideology. There is a good deal of humour in the book too, much of it squirrelled away in footnotes. John Murray, £20

France: A History From Gaul To De Gaulle

John Julius Norwich

Despite the fact that more than 5.5m Britons visit France each year, we remain woefully ignorant of its history. As Lord Norwich points out: ‘We may know a bit about Napoleon or Joan of Arc or Louis XIV, but for most of us that’s about it.’ This enjoyable book, covering two millennia of French history at a brisk canter, is his attempt to fill this lacuna. It is old-fashioned history, recounting the deeds of emperors and kings, dukes and popes, heroes and villains.

It has nothing to say about economics or industry and little about France’s wondrous culture, her architecture, art and literature, let alone her food or her wine.

The tone of France is avuncular, worldly and witty; it is like having dinner with an urbane, well-read uncle. It is spiked with commonsensical judgments: ‘The Crimean War… was a ridiculous affair which should never have occurred at all.’ Norwich has been visiting France all his life; indeed, his father, Duff Cooper, was British Ambassador in Paris immediately after the Second World War. The book is enlivened by the author’s own anecdotes: for example, he recounts his father presenting medals to veterans of the Resistance with tears pouring down his cheeks.

This is a history of France but reading it, you are forcibly reminded how closely intertwined it is with Britain’s own story. From the time of Julius Caesar great tracts of British and French history are incomprehensible without the other. For long periods in the Middle Ages English kings claimed to rule swathes of western France; the Hundred Years’ War and much of the history of the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries is the story of conflict – and periodic cooperation– between the two nations. Indeed, on occasion Norwich has to remind himself that he is writing French history. If you are planning a trip to France this summer, buy this book and dip into it as you sit soaking up the Provençal sunshine, pastis in hand. You won’t regret it. John Murray, £25

Monsieur X

Jamie Reid

Patrice des Moutis was a French aristocrat who waged war on the P.M.U., France’s state-owned betting system. In the late 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s he won huge sums playing the tiercé, a combination bet in which the punter predicts the first three horses home in a race. The P.M.U. did all it could to stop des Moutis winning and gradually the story darkens before reaching a tragic end. Reid’s prose rattles along, bringing vividly to life the glamour and turmoil of France in the three decades after the war. Bloomsbury, £18.99

The Krull House

Georges Simenon

Set in a small town in rural France on the eve of the Second World War, this story – first published in 1939 – is about hostility to outsiders and how easily suspicion and distrust can descend into violence. The trouble starts when a local girl is found in the canal having been raped and murdered. Suspicion falls on Hans, an amoral, louche cousin of the Krull family, German immigrants who run a local bar and grocery, setting neighbour against neighbour and the family against itself as the story reaches a sad, violent end. Penguin Classics, £10.99

Renoir’s Dancer

Catherine Hewitt

This life of Suzanne Valadon is as much a history of the French art world between the 1880s and the 1930s as it is a biography. Valadon was born in obscurity in 1865 but moved to Paris as

a child. She began modelling for artists as a teenager and posed for a number of well- known painters, including Puvis des Chavanness, Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec; with most of whom she also had affairs. By the mid-1890s, she was an accomplished artist in her own right, with a reputation which grew steadily throughout the rest of her life. Icon, £25

The Devil’s Half Mile

Paddy Hirsch

Paddy Hirsch’s first novel is a gripping crime thriller set in New York City in 1799. It straddles the rough world of the docks where the rival immigrant groups fight for dominance and the supposedly more civilised world of Wall Street – the Devil’s Half Mile of the title – where greed and hypocrisy run riot. In both worlds casual violence is never far from the surface.

The novel’s hero, Justice Flanagan, lawyer, amateur pathologist and detective, has a foot in both camps: he dresses well but carries a flick-knife. He had taken part in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, where he learned to defend himself and inflict pain with speed and precision but is also at home in the coffee houses and brokers’ clubs. His father had been ruined by financial speculation and fraud while his uncle, a slum landlord and racketeer, controlled the city’s waterfront and wharves.

As Justice digs deeper into the story of his father’s death,

he unearths a sleazy, violent world of slavery and prostitution. Hirsch creates a vivid portrait of New York at the end of the 18th century. It is a city of stark contrasts: the slums, the poverty and the degradation of the masses contrast with the stone houses, carriages and wealth of the upper classes. His descriptions of the crime, filth and stench of the city are reinforced by the slangy idiom and patois with which the characters speak. It’s a compelling story with strong characters and some scenes of extreme violence, convincingly (and wincingly) rendered.

At the heart of the novel is financial chicanery, slavery, racism and hypocrisy: part of the plot revolves around an early example of a Ponzi scheme. Speculators, lured by big returns, are happy to turn a blind eye to the human misery off which they feed and the wider consequences of their actions. Silently, Hirsch invites his readers to consider the parallels between the mores of Wall Street in the 1790s and the 21st century. Corvus, £14.99

The Restless Sea

Vanessa de Haan

The Restless Sea is a historical romance, a tale of love and class, set during World War II against the unusual background of the Russian convoys. Charlie, an upper-class Fleet Air Arm pilot and Jack, an East End scallywag who joins the Merchant Navy to escape the law, compete for the affections of Olivia. The action sequences – as when Charlie’s squadron of Swordfish attack a German battleship – are well done and de Haan’s grasp of the history is sound. The characters can seem somewhat stereotyped, and the prose breathily overwritten in places, but overall it’s an enjoyable romp. Harper Collins, £14.99

Ultimatum

Frank Gardner

Here is a pacy, enjoyable thriller which describes the kidnap in Iran of the British Foreign Secretary and the operation to rescue him. Frank Gardner, who has been the BBC’s Security Correspondent since 2002, tells the story with a verve and expertise born of long experience of the subject. The operational and governmental detail is convincingly authentic. It is the thriller writer’s trick to blur the boundary between current affairs and invention, to make the unthinkable thinkable and exciting. In this, Gardner succeeds triumphantly. The short, one-subject chapters and the taut prose keep the pages turning right to the end. Bantam Press, £12.99

Killer Intent

Tony Kent

Tony Kent’s debut novel is a contemporary political thriller

set in London and Ireland. The plot is exciting if perhaps a little far-fetched in places while the hero who, like the author is a barrister, seems on occasion to be imbued with superhuman powers. Some of the action scenes are shockingly, callously violent but brilliantly described. The book, although occasionally let down by the irritatingly staccato prose and its willingness to resort to cliché, is a fine achievement for a first novel. Kent, a well-known figure at the Old Bailey, has signed up with the publisher for another 13 novels so we shall be hearing more of him. Elliott & Thompson, £12.99

The Weather Detective

Peter Wohlleben

Peter Wohlleben is a German forester, a man with deep connections to the natural world, and his book is a treasure trove of fascinating information about the environment, a primer for the scientifically illiterate but curious gardener: for example, the formation and ring-ageing of hailstones or the reasons why one should not overwater one’s garden in a heatwave. He also offers easily digestible summaries of wider matters such as global warming and soil damage. A book to browse and then think to yourself, ‘Oh, so that’s why.’ Rider, £12.99

Till the Cows Come Home

Philip Walling

‘It is impossible to overstate the services rendered by the ox to the human race.’ So says Philip Walling at the beginning of his book about man’s relationship with bovines. Cattle have been domesticated for 12,000 years and there are now more than a billion of them on the planet. Walling, a farmer-turned-barrister, explores this long relationship and investigates some of the better-known breeds – including the Longhorn cattle of America’s Wild West and Spain’s fighting bulls. The book is also a hymn to the benefits of humane husbandry and the proper management of land, practices often at odds with ecological ideology and fashion. Atlantic Books, £14.99

Chasing the Ghost

Peter Marren

This book tells of Peter Marren’s campaign to locate the 50 species of British wild flower – there are more than 1,400 in all – which had eluded him in a lifetime’s botanising. His quest takes him from England’s south coast to the northernmost shores of Scotland with many a wood, bog and moor along the way. It is a charming, somewhat eccentric book, part botanical adventure, part rumination on man and nature with a dash of anecdote and autobiography thrown in. At its heart are wild flowers which, Marren writes, offer ‘a kind of inner calm, a feeling of oneness with nature.’ Square Peg, £16.99

Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

Thor Hanson

There are more than 20,000 species of bee on the planet, inhabiting every continent bar Antarctica. Man’s relationship with the bee goes back to prehistory. ‘No other group of insects has grown so close to us, none is more essential, and none is more revered.’ For millennia, honey was man’s best source of sweetness and its wax invaluable for lighting, writing and sealing. Buzz is an engaging mix of science, history, anecdote and geeky good humour. Hanson, an American biologist, wears his learning lightly, getting the science across without being dull or pedantic.

Bees developed as a strain of vegetarian wasp. Wasps kill and eat other creatures but bees adapted to feed only on pollen from flowers. From this they fed themselves and their young and made honey for the winter. In the process they took on the vital function of pollination. Flowers, in order to propagate, began to make themselves alluring to bees by adopting colour and scent. It is evolution’s virtuous circle in action.

And, of course, it is pollination that makes bees so important to us. ‘It’s often said,’ writes Hanson, ‘that every third bite of food in the human diet relies upon bees.’ It is why the recent decline in bee populations – known scientifically as Colony Collapse Disorder – matters greatly. Hanson lists 150 crops, many of them staples, which require pollination by bees. To illustrate his point he conducted a cod scientific experiment: deconstructing a Big Mac, separating the elements derived from sources which require pollination from those which do not. He concludes that ‘we could still eat in a world deprived [of bees], but eating would be extremely dull (and not very nutritious).’

As a cautionary tale of what can happen when bee populations collapse, Hanson tells the story of the Maoxion Valley apple orchards in China. The swift decline in bee numbers in the valley – caused by pesticides and loss of habitat – wiped out the orchards leading to the mass felling of the trees. Bees do matter. Icon, £20

Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975

Max Hastings

The Vietnam War, from the mid-1960s until 1975, was violently controversial: its protracted agony divided nations and generations, causing political upheaval and civil unrest on an unprecedented scale. It was the Great Event of its time. Yet, in this country certainly, I suspect that the majority of people under the age of 60 know very little about it. There is a miasma of myth, half-truths and downright lies surrounding the war which Sir Max Hastings’ new history dispels utterly.

Hastings writes with the benefit of personal experience: he reported on the war, both from the United States and Indo-China itself, and met some of the leading protagonists. He was helicoptered out of the US embassy compound in Saigon in April 1975 as the waters of defeat and humiliation closed over the Americans. He has folded into the narrative the accounts of scores of participants from both sides, giving the book an electrifying immediacy. It imparts vividly the terror of the American infantryman – the ‘grunt’ – inching through the jungle or wading through a swamp never knowing where the next trip wire was or when the Vietcong would open fire. Likewise, Hastings brings to life the airborne war: ‘the clatter

of rotor blades,’ was, he writes, ‘the struggle’s orchestral music.’

Vietnam begins with the French struggle after 1945, subsidised by the Americans, to defend their colonies in Indo-China against the communists. It charts the gradual enlargement of the American presence in South Vietnam under Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy up to the point when President Johnson overtly committed US forces to the theatre. Hastings lays bare the self-deceptions and equivocations which dogged American policy throughout the war as well as exposing the North Vietnamese regime for

the brutal totalitarian regime it was.

Hastings has a historian’s grasp of narrative and a journalist’s eye for the story and the telling detail. His consistently lively, engaging prose rattles along making light of the book’s 650 pages. This is important, gripping history: read it. William Collins, £30

Devices and Desires: Bess of Hardwick and the Building of Elizabethan England

Kate Hubbard

Devices and Desires is by no means the first biography of Bess of Hardwick, that formidable Elizabethan matriarch, builder and woman of business, nor the only book about Hardwick Hall, but it is an enjoyable retelling of Bess’s long and remarkable life – she died in 1608 in her mid-eighties – and her astonishing impulse to build. In all, she built four houses but her principal memorial is Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, built in the 1590s. Chatto & Windus, £20

The Quest for Queen Mary

James Pope-Hennessy, edited by Hugo Vickers

In 1955 James Pope-Hennessy was commissioned to write the authorised biography of Queen Mary, consort of King George V. This new book contains his notes made of the interviews he conducted with the baubles of minor European royalty and aristocracy while researching the book, edited with hushed reverence by Hugo Vickers. It is, in effect, the out-takes of a royal biography and much of it is very funny. Pope-Hennessy had an acute eye: he interviewed one German princess who was ‘enormously fat, with a huge red face like an old baby’. Zileika, £30

The British in India

David Gilmour

The British in India is a dazzling, beautifully written panorama of the lives of Britons in India over more than three centuries. The breadth of Gilmour’s coverage is extraordinary, chronologically, geographically and socially, roaming over the entire subcontinent, taking in the whole of the British experience of India. His cast ranges from squaddies to governors, via planters, railwaymen, boxwallahs and bureaucrats. Nor does he forget the women who, often reluctantly, followed their menfolk to India, or those on the periphery of the Raj, the Eurasians, floating hybrids, not wholly British but not wholly Indian either. Allen Lane, £30

My Sister, The Serial Killer

Oyinkan Braithwaite

Blood, they say, is thicker than water – but it is also more difficult to get out of the carpet. Oyinkan Braithwaite’s first novel is a story steeped in the stuff: it opens with the narrator helping her sister, Ayoola, remove all traces of blood from the bathroom in which she has just murdered her boyfriend and is dominated by the visceral strength of the blood ties which, for better or worse, bind families together.

Set in Lagos, Nigeria, the central characters, are two sisters, Korede and Ayoola. Korede, the elder, is a nurse at a local hospital while Ayoola is a fashion designer. As siblings, they present a striking contrast: Korede, the guardian angel, is kind, loyal, and altruistic, if perhaps misguided; Ayoola, the femme fatale, is manipulative, selfish, shallow and, repeatedly, murderous. Where Rekede is reserved, mildly self-conscious, and kind, Ayoola is grasping, beautiful and cruel.

The sisters come from a comfortable, middle-class Nigerian background overshadowed by their late father, domineering, unfaithful and violent man, feared and despised by his family. His behaviour, glimpsed in flashbacks, may, we are invited to conclude, explain if not excuse his younger daughter’s murderous contempt for men.

My Sister, The Serial Killer is a darkly comic, highly enjoyable novel. Braithwaite writes with deadpan humour which, combined with a delicious, oblique turn of phrase, prevents the novel from becoming depressing or overly serious. The subject matter may be deadly, but in Braithwaite’s hands it never loses its humour or its sense of mischief.

It comes across as a spare, stripped-down story – reflected in the prose – one which concentrates on the murderous and comic essentials. In fact, the novel is more complex, addressing starkly the eternal conflict of Good and Evil and the capacity of family loyalty to corrupt the most scrupulous of consciences. There is no such thing, Braithwaite seems to be saying, as immutable morality, absolute right and absolute wrong: family and blood trumps all.

Jeeves and The King of Clubs

Ben Schott

Ben Schott, he of the eponymous Miscellany, has published his first novel, ‘an homage to PG Wodehouse’. It succeeds triumphantly, both as light entertainment and as a tribute to the Master. Schott resurrects some of Wodehouse’s best-loved characters: Aunt Dahlia, Madeline Bassett and the sinister Roderick Spode, amongst others, all of whom have a part to play. He captures perfectly Bertie Wooster’s empty-headedness and cheerful philistinism and has a fine Wodehousian turn of phrase. A club bar is described as being ‘so full of boozy congeniality and pink gin that it might have been a Gillray cartoon sprung to life.’

Hutchinson, £16.99

Loyalties

Delphine de Vigan

Delphine de Vigan is a best- selling novelist in her native France; her new novel weaves together four separate stories which deal unsparingly with the effects of divorce, betrayal, child alcoholism and loneliness. The four strands of the narrative, the stories of two 13-year-old boys, Theo and Mathis, their teacher Helene and Mathis’ mother, Cecile, engage and disengage with each other as the book progresses. It’s a deceptively simple novel, an impression enhanced by the unfussy prose, shorn of literary flourish or artifice, but a powerful, thought-provoking one.

The Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories

Edited by Jay Rubin

Japanese literature is not widely read in the West. This anthology reveals a rich mosaic of Japanese life and culture. There is the gory horror of ‘Patriotism’, which describes a hara-kiri in all its fanatical devotion to duty and honour, incongruously wrapped in a shroud of eroticism. There are some affecting stories about the disasters which have struck Japan, including the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the 2011 tsunami. But there is humour and beauty, too: ‘The 1962/1982 Girl from Ipanema’ is a whimsical tale of nostalgic memory.

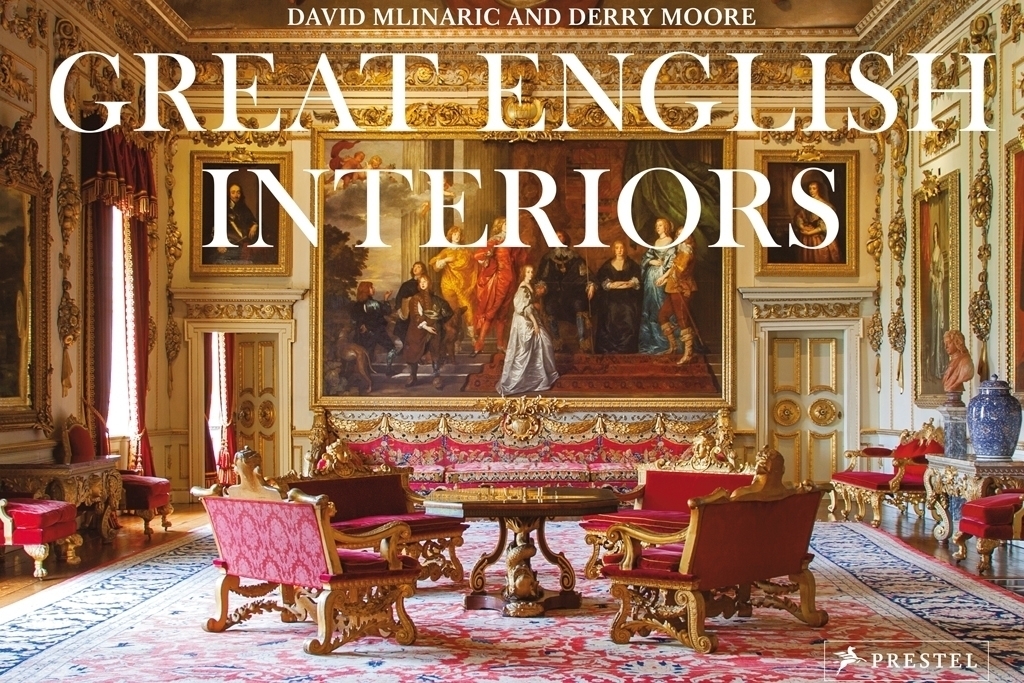

Great English Interiors

By David Mlinaric and Derry Moore

This beautiful book is the latest fruit of the long association between David Mlinaric, the high priest of British interior designers, and Derry Moore. In this book, Moore’s sumptuous photographs bring vividly to life the interiors chosen by Mlinaric from the austere beauty of Haddon Hall to the florid extravagance of le goût Rothschild at Waddesdon.

The book follows the development of English interior design century by century, from its beginnings in the 15th century to the present day. ‘The medieval ethos was one of security, not comfort,’ writes Mlinaric. Each chapter includes a brisk survey of the evolution of interior design in the period as a preamble to a more detailed examination of the interiors of houses which Mlinaric considers to exemplify the taste of the period. Thus the 18th century is illustrated by reference to Houghton Hall, West Wycombe Park, New Wardour Castle, Syon House, Heveningham Hall and Spencer House in London.

Mlinaric is a worldly, witty guide who writes well, with – as one might expect – an acute eye for the effects of colour and light and deep knowledge of his subject. Along the way, we learn about Mlinaric’s own tastes: he declares, for example, that the entrance hall at Heveningham Hall in Suffolk ‘is one of my favourite rooms in the country’. The book is made more interesting and more authoritative by the fact that Mlinaric has worked in many of the houses discussed – for example, Chatsworth and Spencer House. It is also leavened with anecdotes bringing these imposing houses and the grandees of the world of interiors to life. Mlinaric clearly admires the work of the celebrated decorator John Fowler, whose lightness of touch and refined aesthetic sense can still be seen in some of the houses featured here.

Great English Interiors is much more than just another prettily illustrated coffee table book about nice houses. It is an interesting, informed guide to the history of English interior design written by one of its masters and accompanied by stunning photographs.

Ghost Trees: Nature and People in a London Parish

By Bob Gilbert

Ghost Trees is a spirited defence of the importance of recognising nature in our cities. Bob Gilbert moved to Poplar when his wife was appointed its rector and set about exploring this much-changed part of east London. This is a lyrical book of great imaginative scope, contemptuous of the nostrums of modern capitalism. He finds nature’s beauty in the most unexpected places: the kingfisher on the banks of an urban canal or the lichen on a tree. It is filled with fascinating nuggets of information; for example, in 1917, Poplar’s schoolchildren gathered conkers for the manufacture of acetone, a vital ingredient of cordite.

Glasshouse, Greenhouse

By India Hobson and Magnus Edmondson

Motivated by the connection between ‘engineering and nature’ India Hobson and Magnus Edmondson travelled the world visiting and photographing glasshouses, from the great Victorian structures such as Kew to modern municipal projects via a plethora of smaller, private undertakings as far apart as the United States and Australia. The commentary is written in the first-person plural giving it a homespun, wide-eyed feel, revealing a Pooterish concern about the weather – ‘it usually rains wherever we go’ – and the demands it makes upon our intrepid explorers.

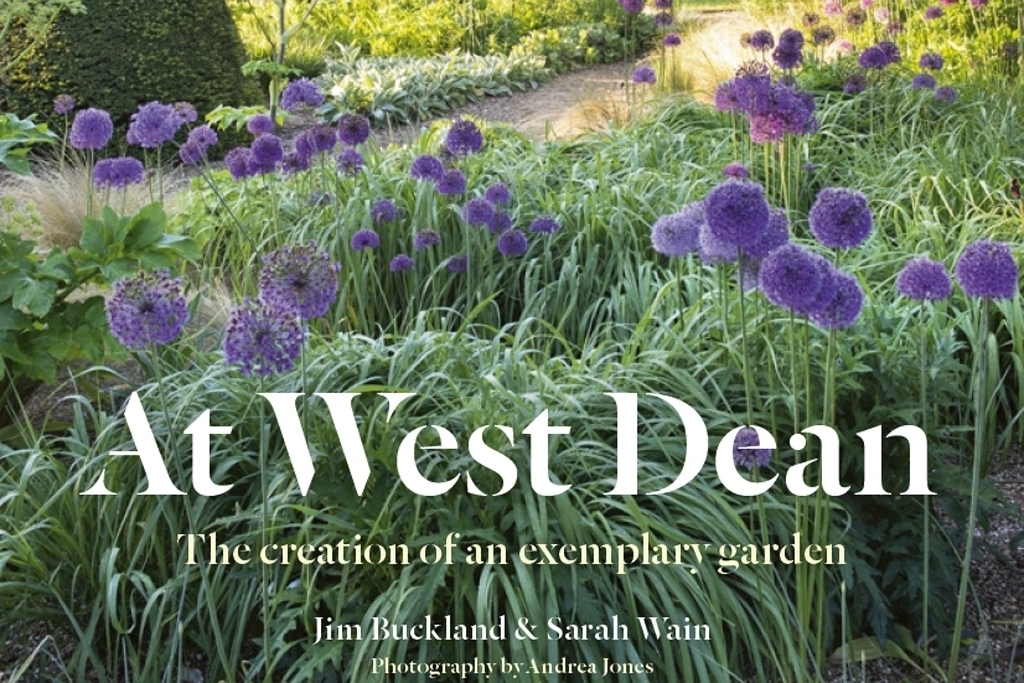

At West Dean

By Jim Buckland and Sarah Wain

Jim Buckland and Sarah Wain arrived at West Dean in Sussex in 1991, after the ‘arboreal Gotter-dammerung’ of the Great Storm of 1987 had laid waste to the estate. This book, part history, part ‘how-to-do-it’ guide and part treatise on the theory of garden design, tells the story of their regeneration of the garden. It conveys the daunting work and organisation which goes into creating and maintaining a 90-acre garden as well as the joy of the never-ending cycle of the seasons and the wonder of nature vividly captured in Andrea Jones’ photographs.

How to Give Up Plastic

By Will McCallum

The tsunami of plastic smothering our planet’s oceans is an ecological catastrophe, at least as threatening as the menace of global warming. Millions of people watching Sir David Attenborough’s Blue Planet II saw an albatross feed its chicks small pieces of plastic in the mistaken belief that they were food.

This book is a wake-up call and a guide. McCallum is a crusader but never loses sight of the fact that we all, however committed we may be to reducing our use of plastics, have lives to lead. It is this reasonableness, this practicality, which gives the book its force. ‘Every victory against plastic,’ he writes, ‘begins with a single person or small group of people deciding that the time to take action is now.’

Root to Stem

By Alex Laird

This, the author’s latest book is a hymn to ‘a seasonal and holistic approach to health that puts plants, herbs and nature at the heart of how we live and eat.’ She advocates the benefits of eating ‘whole food’ in its natural state; skin, pith, seeds and all. The benefits of this approach are wide ranging: it improves our diet and it’s good for the planet. The book offers common-sense advice about foraging for wild food, season by season, and ways to prepare it as well as a host of natural remedies for afflictions as varied as air-sickness and asthma.

The Foraged Home

By Joanna Maclennan and Oliver Maclennan

Architectural foraging takes many forms, from collecting a few seashells to decorate a wall to amassing the wherewithal to build an entire house. The Foraged Home covers the whole spectrum, from beach shack to Georgian townhouse, by way of an upturned boat, an artist’s cabin and a caravan. Foraging constitutes, say the authors, ‘a modest push against consumerism and increasing waste.’ The ecological message aside, much of the pleasure of the book lies in Joanna Maclennan’s inspiring photographs which bring to life architectural foraging as far afield as north Devon, Cape Cod, Queensland, the Norwegian fjords and rural Bulgaria.

Still Water

By John Lewis-Stempel

This book celebrates the pond, once an indivisible part of the imagined Victorian rural idyll, along with half-timbered cottages and bewhiskered yokels. There were 800,000 ponds in Victorian England; now there are 470,000 of which 80 per cent are polluted or in need of maintenance. Lewis-Stempel is a prolific and accomplished nature writer, whose ruminations on the fate of our countryside and its management are trenchantly and beautifully expressed. His investigation of the pond takes him along many a byway, some nostalgic, some amusing but all enlightening. He finds beauty and wonder wherever he looks, even in the humblest leaf.

Beached In Calabria

By Ian Ross

Beached In Calabria is the newest memoir from Ian Ross, the man behind Rocking The Boat and Beverly Hills Butler. It tells the amusing tale of Ross’s decision to buy a house in the southern province of Reggio Calabria big enough to fit his 27+ strong family – unbeknownst to his wife. A great read if you’re interested in travel writing and Italian culture, or just fancy a laugh.

The Art of Love: The Romantic and Explosive Stories Behind Art’s Greatest Couples

By Kate Bryan

Kate Bryan’s new book looks at some of the art world’s most fascinating couples, from 1880 to the present day. From long-lasting romances to secret affairs, she explores how romantic relationships between two artists can affect the art they produce – both in good and bad ways. Couples profiled include Lee Miller and Man Ray; Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson; and Frida Khalo and Diego Riviera.

Hudson’s Kill

By Paddy Hirsch

This novel revisits early-19th century New York, also the setting for Paddy Hirsch’s first novel, The Devil’s Half-Mile. It is a rapidly-expanding city where abject squalor co-exists with great wealth, where seething slums are but a few streets from the stone townhouses of the shipowners and Wall Street brokers. Hirsch brings this world of violence, crime and racial hatred vividly to life. Justy Flanagan, lawyer, amateur pathologist, detective and city marshal, the hero of Hirsch’s first novel, is confronted with a gruesome murder, which he must solve before the city’s tensions explode into violence.

The Dragon Lady

By Louisa Treger

The lives of Stephen and Virginia Courtauld are well documented, their taste and wealth forever commemorated in the astonishing Art Deco interiors they installed at Eltham Palace. Louisa Treger’s second novel charts their life in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) during the 1950s. The Courtaulds’ life of pampered opulence and their liberal opinions set them apart from their colonial neighbours. This promising story of prejudice and racial conflict at the end of the Empire is, unfortunately, spoiled by the author’s all-too-ready resort to breathy, emotional flourishes and a smattering of historical solecisms.

A Single Source

By Peter Hanington

The author’s second novel is a thriller set against the background of the Arab Spring. The protagonist is William Carver, a hard- drinking, cynical BBC foreign correspondent, an enjoyable character – if perhaps a little stereotyped – who, in the course of reporting the popular uprisings in Cairo in 2011, uncovers skulduggery in the arms trade and government. The descriptions of the civil unrest in Cairo are convincingly atmospheric. The novel has much to say about people trafficking and the brutal treatment of migrants, as well as Western governments’ ambiguous relationships with the arms trade.

What Happens Now?

By Sophia Money-Coutts

‘Slowly, slowly like a Harrods’ lift at Christmas, Lysander progressed downwards …’ Thus Jilly Cooper described the bounder-hero of her 1993 bonkbuster The Man Who Made Husbands Jealous, seducing one of his many conquests. The phrase neatly epitomises the winning combination of humour, sex and class which made Mrs Cooper’s novels so popular. Sophia Money-Coutts’ new novel, the follow-up to her debut The Plus One, manages triumphantly to transpose the formula to 2019 London. Here, the world of social media and online dating rubs shoulders with the age-old pitfalls of unplanned pregnancy, deceitful men and snobbery. What Happens Now? is as light as a Fulham yummy mummy’s egg-white omelette – but infinitely more appetising.

Lil Bailey, the heroine, teaches in an expensive primary school, St Lancelot’s, in Chelsea. Her class consists of four English boys called George, Arthur, Cosmo and Phineas, the son of a Russian steel magnate, a Greek prince, an American, an Indian and the son of a Premiership footballer. This affords Money-Coutts ample opportunity to make fun of the habits and aspirations of London’s super-rich, something she does with great brio. The children are collected after school by bodyguards and nannies more often than by their expensively Lycra-clad mothers. At Christmas, Lil is given a pot of caviar costing £843 from Fortnum’s. One mother complains that her precious son has been given apple crumble for pudding at lunch: ‘It’s just way too much refined sugar,’ she says.

The novel tells the story of Lil’s affair with Max, a handsome, wealthy, aristocratic mountaineer. She unintentionally becomes pregnant when they have sex on their first date, but the path to true love is far from smooth. There is, however, much fun to be had along the way. Money-Coutts, as befits a former Tatler Features Editor, is well versed in the eccentricities of the British upper classes and writes convincingly about them. She writes with humour and gynecological gusto about masturbation and childbirth, too. A perfect holiday read, with a pastis by the pool.

To The Lions

By Holly Watt

Holly Watt is a well-known investigative reporter who made her name uncovering the Westminster expenses scandal. To The Lions, her first novel, won the Crime Writers’ Association Ian Fleming Steel Dagger award. As befits an investigative reporter, this is a thriller in which the story is the story. Ace reporter Casey Benedict stumbles upon a conspiracy which she then pursues with all the guile and tenacity of her trade.

The action moves from her newspaper’s high-octane, foul-mouthed London newsroom to the desolate wastes of the north African desert via louche bars in Mayfair, swanky clubs on the Côte d’Azur and human tragedy of the Middle East’s refugee camps. Watt is good on the mechanics of establishing a story and adept at conjuring up the cynical self-indulgence of her characters.

Launch Code

By Michael Ridpath

A thriller with a more subtle, reflective tone – its origins lie in events which took place on an American nuclear submarine deep beneath the Norwegian Sea in autumn of 1983. The novel winds up more circumspectly than in many thrillers, flipping between the present and the past, but is full of convincing detail, in this case the US naval protocols for nuclear engagement. At the heart of this story is a moral dilemma about conflicting loyalties.

Die Alone

By Simon Kernick

A more traditional thriller; its heroes are two tough ex-cops, one of whom, Ray Mason, is in prison for murder. The villain is a British politician with aspirations to No. 10 Downing Street, no less, with long-standing links to organised crime and a taste for raping and murdering young women. The story races along in spare, thriller-writer’s prose, full of practical and operational detail, a world of tangled motives and divided loyalties, before reaching an action-packed climax.

Three Hours

By Rosamund Lupton

A terrific novel, which grabs the reader from the first page. It tells the story, minute by minute, of an attack by two gunmen on a school in rural Somerset on a snowy November morning. It is every parent’s worse nightmare: we know it happens – we’ve seen it on TV – but cannot imagine that it will ever happen to us. But here, on a school day like any other, it does.

Lupton weaves together the different strands of the story: the unfolding horror seen by the captive children and staff inside; the wary, determined police and the distraught parents on the outside. The novel tells a story of compulsive horror in the course of which it touches on many themes which confound modern society.

Teenage alienation, and parental incomprehension and helplessness in the face of it, is a major theme of the novel, as is the radicalisation of young people and the role of social media. This is a thriller but it says much about uncomfortable subjects we all prefer not to address.

Quixotic Nature

By F Khorsandjamal

A book of love poems that’s at once deeply personal and completely universal. Fad Khorsandjamal’s new collection of poetry, Quixotic Nature, explores love in four of its forms: familial love, friendship love, romantic love and self love. At times raw and poignant, at others hopeful, it’s a book that will comfort and uplift anyone who’s ever experienced loss and suffering. So that’s all of us, then.

Three Bedrooms in Manhattan

By Georges Simenon

First published in 1946, this is an intense, atmospheric account of a passionate affair between François, a French actor whose career and life is on the slide, and Kay, a woman of middle European origins with a tangled background. Simenon brilliantly and sparely recreates the New York of the time – the all-night diners, the sleazy bars, cheap hotels and threadbare apartments. It’s a story about love and jealousy, about wildly oscillating emotions, desire and need, certainty and uncertainty, rationality and irrationality. Its claustrophobia heightens the emotions and sharpens the drama. In the midst of the big city, surrounded by millions of people, all that matters, Simenon seems to be saying, is a man and a woman in love.

Somerville’s War

By Andrew Duncan

The book begins in Somerville, an imaginary town on England’s south coast, closely corresponding to Beaulieu. The Special Operations Executive (SOE) requisition a house as a training base, and the early chapters revolve around the residents, a disparate cast of toffs, misfits and oddballs and their new neighbours, who include Adrian Russell, a fictionalised Kim Philby. Once it leaves Somerville, the novel gets into its stride: young Leo Maxwell joins the ATA and starts flying Spitfires. There is a high-octane account of aerial combat over the Channel before the scene shifts to the covert SOE operation in occupied France that brings the story to an exciting climax.

Ashes

By Christopher de Vinck

One theme that The Vanishing Sky shares with Ashes is the kindness of strangers to refugees in the direst of circumstances. The twelve-year-old Georg Huber is taken in by an elderly peasant woman and a kindly priest during his wanderings across war-torn Germany. Likewise, the young heroine of Ashes, a refugee from Brussels, is sheltered by a wealthy widow in Biarritz.

Ashes is set in Brussels in 1940, as the Germans invade Belgium. It tells the story of two 18-year- olds, Simone and Hava. They are contrasting characters: Simone is sensible, grounded and practical, Hava a free spirit, whimsical and imaginative. De Vinck recreates vividly the mixture of blind panic, hopeless optimism and black despair with which the population reacted to the invasion. The moving spirit of the novel, however, is the genocidal antisemitism of the Nazi regime in all its brutality. It’s a good story, vividly told, albeit in parts it would benefit from a lighter, less didactic touch.

The Vanishing Sky

By L Annette Binder

This book tells the story of a German family, the Hubers, charting its disintegration under the stress of war. It’s a story about loss and the damage, mental, physical and material, which war causes and its terrible impact on every aspect of human life. The novel has an unfussy, understated feel – reflected in Binder’s calm prose – that belies its powerful impact. It’s alternately subtle and striking, quiet and then, suddenly, deafeningly loud. Ruminative pastoral scenes give way to a blazing account of an Allied air raid. She has an acute eye for detail: ‘Just smoke and stones and dirty lace curtains’ succinctly describes the aftermath of an air raid.

This Lovely City

By Louise Hare

This spirited first novel tells the story of Lawrie Matthews, a young Jamaican who arrived in Britain in 1948 aboard the Windrush, and Evie, the mixed-race London girl with whom he falls in love. The story is set in the war-damaged streets of south London, in shabby lodgings and smoky jazz clubs, a world of post-war gloom where everything is rationed. Against this background, Lawrie settles into a new life as a postman by day and a jazz clarinetist by night, but a malevolent coincidence intervenes to upend his good intentions. The story jumps regularly – and sometimes confusingly – between 1948 and 1950, but it rattles along. Hare brilliantly recreates the ambience of post-war London, presenting a multi-layered view of the reception accorded to the new immigrants in those early years. There was widespread incomprehension and much racism, institutional and personal, spoken and unspoken, but there was also some acceptance and much kindness.

Homecoming

by Colin Grant

This oral history of the Windrush generation records the immigrants’ story from their backgrounds and childhoods in the Caribbean, their ‘cinnamon-scented’ past, to their often-harrowing early experiences of post-war Britain. The Windrush immigrants were young – the average age was 24 – many of them imbued with an idealised view of Britain, born of an Anglocentric education. On arrival, however, the Caribbean immigrants found Britain pinched, miserable and frequently hostile. Often forced to live in cramped, expensive housing with inadequate facilities, they faced widespread racism at work and in the wider community. ‘To put it bluntly,’ said one, speaking of 1949, ‘the coloured man is not wanted in British industry.’ The treatment meted out to the Windrush generation is a disreputable, shameful episode but here we can listen to that generation telling its story in its own words.

Truth Be Told

By Kia Abdullah

This legal thriller is based on a male rape at an expensive all-boys London boarding school. The victim is Kamran Hadid, 17-year-old son of a wealthy Muslim family. This is not a story set in the more deprived reaches of the British Muslim community: the family live in great comfort in a large house in Belsize Park. The novel’s principal actor, Zara Kaleel, is a Muslim of humbler origins, an ex-barrister with a diazepam habit, who works tirelessly to save Kamran from the law and himself. The story is compelling with an unexpected twist at the end raising interesting questions about race, sex, and cultural identity.

The Doctor Will See You Now

By Amir Khan

This is a roller coaster report from general practice, the NHS’s frontline. Khan is a GP of 15 years’ experience who works in an inner-city practice in the north of England. The book comprises a series of case studies interwoven with much thoughtful comment on the state of the NHS, all recounted anecdotally. It is by turns alarming, sad, uplifting and comic. Khan’s first experience of verbal abuse at the hands of a patient was being told to ‘fuck off’ by a seven-year-old boy during a home visit. The book finishes with an account of the Covid-19 pandemic. ‘It was,’ Khan writes, ‘one of the worst times of my career, but strangely … I never felt more useful.’

Check back every month for new recommendations…

READ MORE (literally):

The Best Art Books Ever | The Best Books about the Russian Revolution | The Best Literary Festivals of 2020

Prefer to listen? Check out our round-up of the best podcasts to download now!