Meet Rebecca Hossack, The Gallerist Championing Aboriginal Artists

By

1 year ago

Rebecca discusses her incredible projects and her passion for the environment

Gallerist Rebecca Hossack is a passionate environmentalist and champion of lesser-known artists for whom a sense of connection is everything, says Charlotte Metcalf.

Interview: Rebecca Hossack, Gallerist

Rebecca Hossack is widely perceived to be on a par with Bruce Chatwin, late author of the 1987 bestseller The Songlines, for introducing Aboriginal culture to Britain. Quite an achievement for a woman who veered accidentally into the art world after a series of serendipitous connections. ‘I’d been studying to be a lawyer in Australia and arrived in England in 1980 to read for the bar. It was against all my convictions, I wasn’t enjoying it and I just hoped I’d have enough time to visit all the art galleries,’ says Rebecca. A chance conversation with a fellow student led her to Christie’s, where she managed to enrol on an art history course.

By 1988 she had her own gallery in Windmill Street. Having earned a little money from selling paintings, she returned to Australia and then began exhibiting the work of Aboriginal artists in England. Her first Aboriginal show was in summer 1988, comprising work by artists like Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, Anatjari, Uta Uta Tjangala, Billy Stockman Tjapaltarri and Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula, from the Papunya community in the Australian Central Desert where the Contemporary Aboriginal Desert Movement had begun in the early Seventies.

More than 40 years on, Rebecca’s reputation as Britain’s leading champion of Aboriginal art is assured. This summer she has been celebrating the 37th edition of Songlines, her annual show of Aboriginal work. For the first time ever, the physically disabled, non-verbal outsider artist Adrian Jangala Robertson left Australia to see his work hanging and in-demand in Rebecca’s gallery.

Thiaba, Carla Kranendonk, 2022. Hand embroidery, beadwork, acrylic and collage on canvas. Courtesy of Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery.

Another artist whose work Rebecca showed was the late and multiple award-winning Emily Kame Kngwarreye. In 2025 Kngwarreye is to have a one-woman retrospective at Tate Modern. This gratifies Rebecca enormously, who wrote to Nicholas Serota, the-then director of the Tate, over 35 years ago to ask if he’d consider exhibiting Kngwarreye’s work or buying one of her paintings. Serota wrote back saying the Tate would never exhibit or purchase such irrelevant work.

‘So often the contemporary art world alights on one star like Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin,’ says Rebecca, ‘and it’s become increasingly preoccupied with money and the next big thing, rather than striving to uncover and nurture real talent. A lot of the artists I’m gravitating towards are either from non-Western cultures because they still have a very strong spiritual element in their work.

‘There’s such a variety of creativity emerging from a deep connection with the earth among the artists living in the Australian Central Desert, whether it’s in their sculpture, carvings, wood, canvas or paper, textiles, quilts, weaves, basketwork or bark paintings from Arnhem Land.’ Arnhem Land is an area six times the size of the UK at the top of the Northern Territory and recent visitors to Rebecca’s gallery will have seen the Aboriginal sculptures, a series of beautiful painted and decorated hollow logs, from there. The installation reflected the cycle of life and death and represented our universal desire to connect with the inexpressible and mysterious.

Night Pool, Night Lights, Laurence Jones. 2022. Acrylic on Belgian linen. Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery.

As well as championing Aboriginal artists, Rebecca has gone out of her way to discover and support mid-career women artists. ‘They’ve probably been at home bringing up their kids and suddenly all the male graduates they were at college with are doing really well,’ explains Rebecca, ‘but it’s really hard for them to break back into the art world because they’re no longer young photogenic things who can grace magazine covers as Hot New Artists. But these women still have that passion and burning desire to paint again and they do it with absolute dedication, late at night or early in the morning or whenever their kids are asleep or out.

‘It’s fantastic to see, and the work is exquisite, many of them focusing on nature and the natural environment. Just take self-taught Hepzibah Swinford, who paints spectacular, abundant arrangements of flowers and foliage in decorative vases, or Abigail McLellan, the Scottish figurative painter, who died in 2009 after battling MS. She produced pared-down images of flowers with the luminosity, simplicity and strength of icons.

‘Sophie Charalambous is half-Cypriot, half-British and her works on paper take such obvious delight in closely observing Cyprus’s flora, fauna and folk art. Ashley Amery is originally from San Diego and her bold, colourful botanical paintings and evocations of landscapes around water and ocean lift the heart. Then there’s G.W. Bot, an Australian artist born in northern Pakistan, who has created her own visual language of signs and glyphs to express her deep spiritual connection with the Australian landscape.’

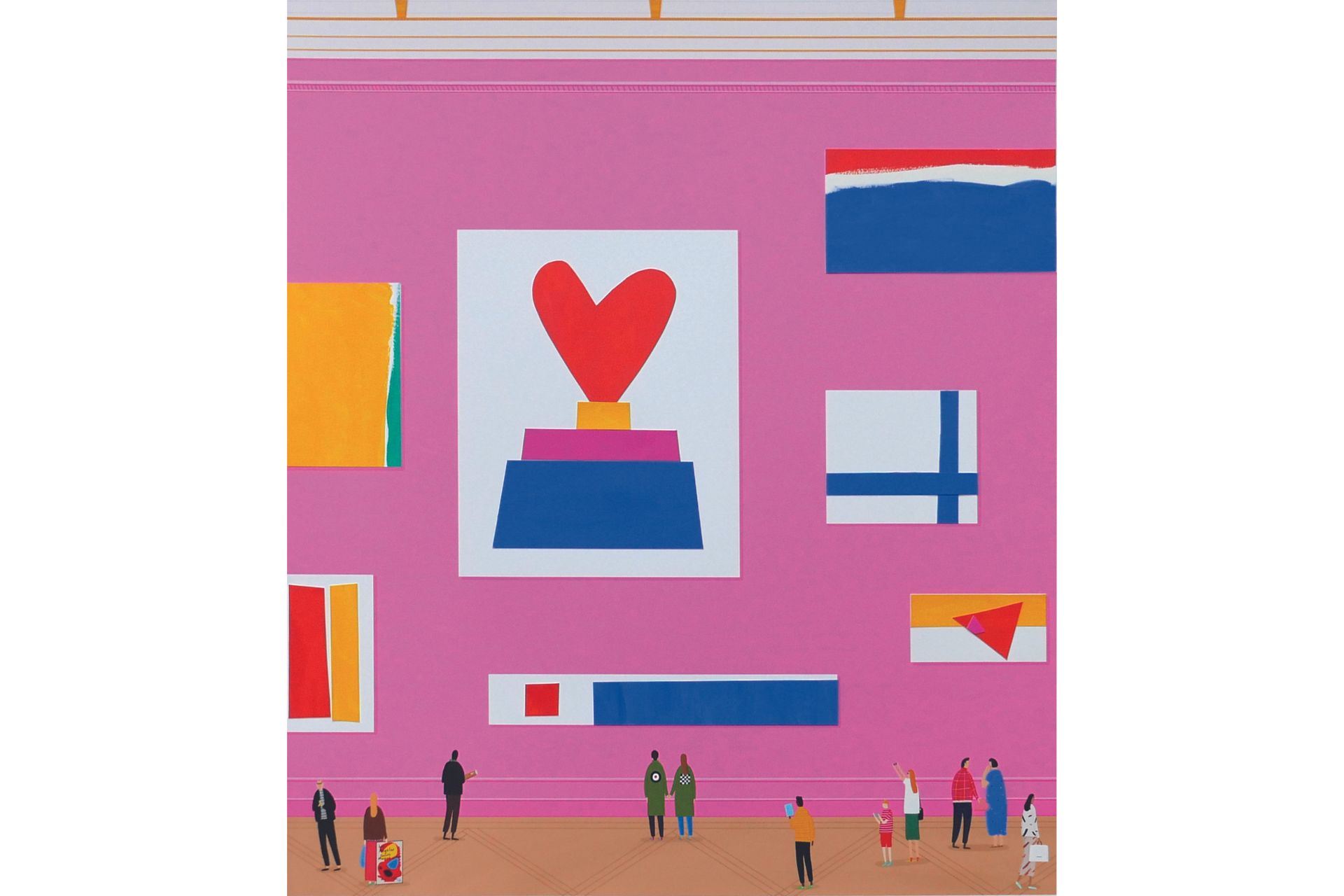

Pink Wall, Rose Blake, 2024. Unique hand-finished print. Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery.

Rebecca’s love of nature extends beyond its representation in art to the long, hard battle she has fought with her local council over the concrete urban environment around her home and gallery under the Post Office Tower. When the council ripped up the first gum tree she planted, she became a crafty green guerrilla warrior, hiring skips in which to plant trees, flowers and grasses. Numerous confrontations followed, culminating in one over a tree during which the council was armed with a chainsaw. But Rebecca prevailed and now her home and gallery are bright with flowers and the area around both is far greener than it was.

She’s also a driving force behind the annual Fitzrovia Arts Festival that unites the for a week of free events ranging from exhibitions, concerts and performances to dog competitions, ballroom dancing for the elderly and guided walks around an area. There is, of course, always an emphasis on the continuing greening of Fitzrovia as Rebecca continues her quest to plant more trees.

‘Everything connects back to nature, just as we all connect with each other,’ concludes Rebecca. ‘E.M. Forster had it right in Howard’s End when he said that we have no purpose without connecting heads and hearts, thoughts and feelings. “Only Connect!” he wrote. And that in many ways encapsulates my life’s work.’