The Exhibitionist: Ed Vaizey on the Mysteries of Tantra

It's time to get tantric

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

Tantra has had female empowerment pegged for millennia, says Ed Vaizey

Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution at the British Museum

What better way to celebrate the mind, body and soul edition of this esteemed magazine than with a long overdue article on tantric you-know-what? Sadly, I only have a few hundred words to share with you on the mysteries of this ancient practice, made famous in modern times by the singer Sting. Allegedly. I think he was misquoted. At least he said he was.

If this article does not fulfil you because of its limited length. But it may have to suffice, as at the time of writing, Britain is in the grip of a permanent coronavirus lockdown. It’s a bit chicken and egg. This therapeutic exhibition might have been just what you needed before three months of self-isolation with your partner. Take this as your ‘what might have been’ moment.

Tantra was due to open on St George’s Day, the day we normally associate with buttoned-up Englishness. Of course, the British Museum would not associate itself with anything too sordid, and this exhibition is designed to set us right about our lazy views of tantra. It’s true that the practice, as the curator of the exhibition Dr Imma Ramos acknowledges, ‘is usually equated with sex in the West.’ But actually it is ‘a radical philosophy that transformed the religious, cultural and political landscape of India and beyond.’

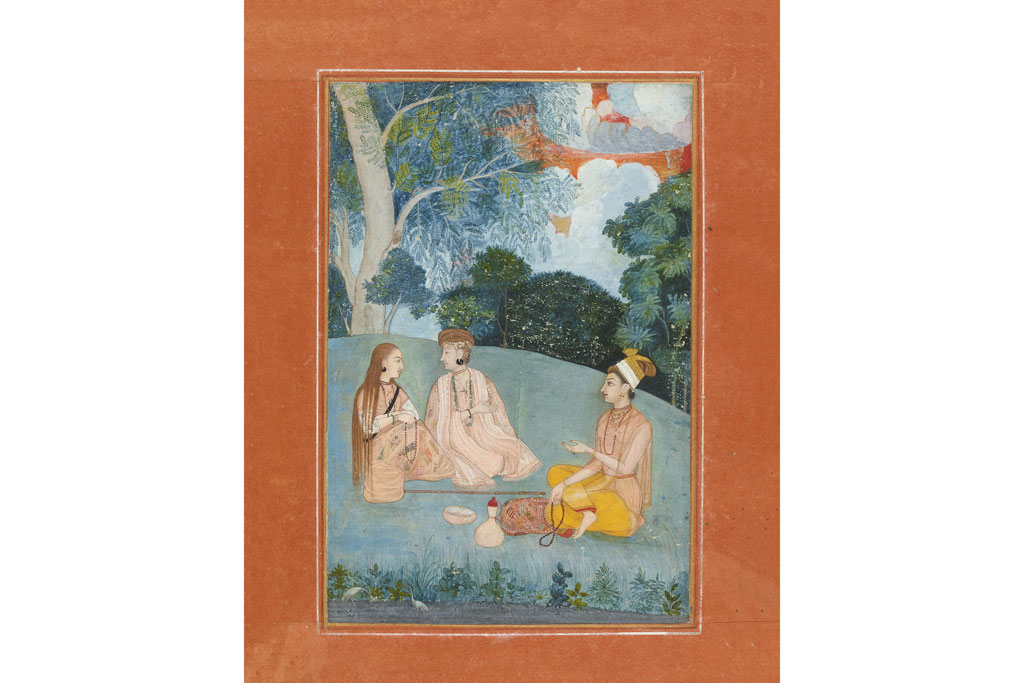

The word ‘tantra’ refers to sacred texts, and indeed four of the oldest surviving texts are on display, on loan from Cambridge University Library, and dating from the 12th century. The texts are instructional, and are written as conversations between a god and goddess. Amazingly, the British Museum has one of the largest collections of tantric material in the world – in total more than a hundred objects are on display.

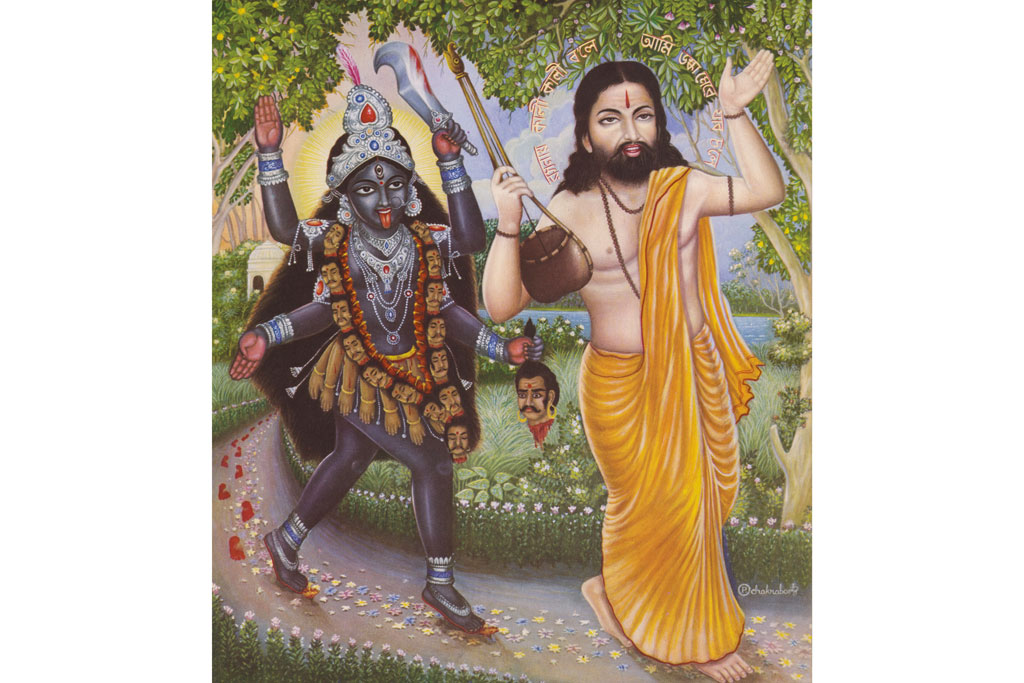

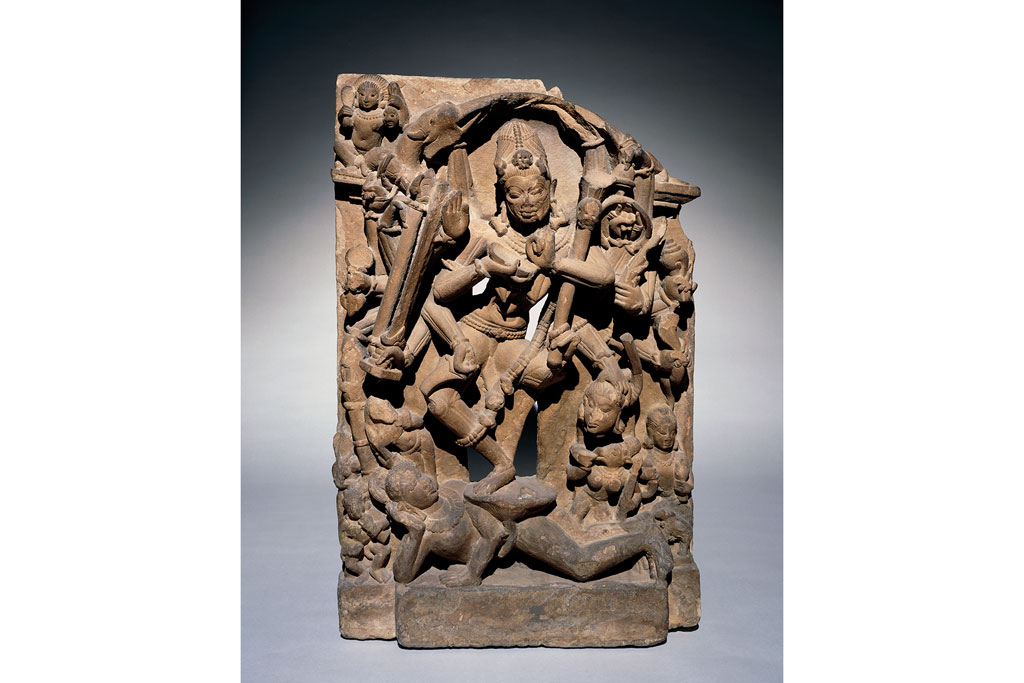

Tantra has acquired its racy image in the West because tantric texts often challenged social and religious norms. This included those of the body and sensuality, and indeed one tantra does focus on the benefits of sexual activity. But this is to reduce the sophisticated impact of tantra on Indian religion. The tantric world view is that everything material is informed by female divine power. Goddesses and female tantric practitioners feature prominently in the exhibition, showing how the philosophy challenged the prevailing view of women’s place in society. That is powerful stuff, brought out further in the exhibition by the display of contemporary works by female artists.

So tantra is a revolutionary philosophy, and indeed became a tool of revolution during the struggle for India’s independence in the late 19th century. Indian goddesses became symbols of India’s fight against colonial rule, and the female image was used to project both maternal strength and destructive power. Tantra’s impact has continued, in the 1960s and 1970s being purloined for imagery to support the countercultural movement.

As you wander round, you will recognise much on display as being typical of the Indian art you may have seen in the past. And you will be surprised to see how, 1500 years later, it played a role in the psychedelic imagery that is much more familiar to the modern eye. I am not sure an hour here will improve your sex life. But it will be good for the soul, great for yoga, and fabulous for challenging misconceptions. Maybe you can experience it virtually.

The British Museum, and subsequently this exhibition, is currently closed, but you can explore the British Museum online. britishmuseum.org

MORE EXHIBITIONIST:

Art’s Answer to Big Tech / The Uplifting Powers of Pottery / Bags! at the V&A: Examining the Humble Handbag