Scrapes, Scandals and Storytelling with Theo Fennell

By

3 years ago

His hilarious new memoir is a celebration of adventure and ingenuity

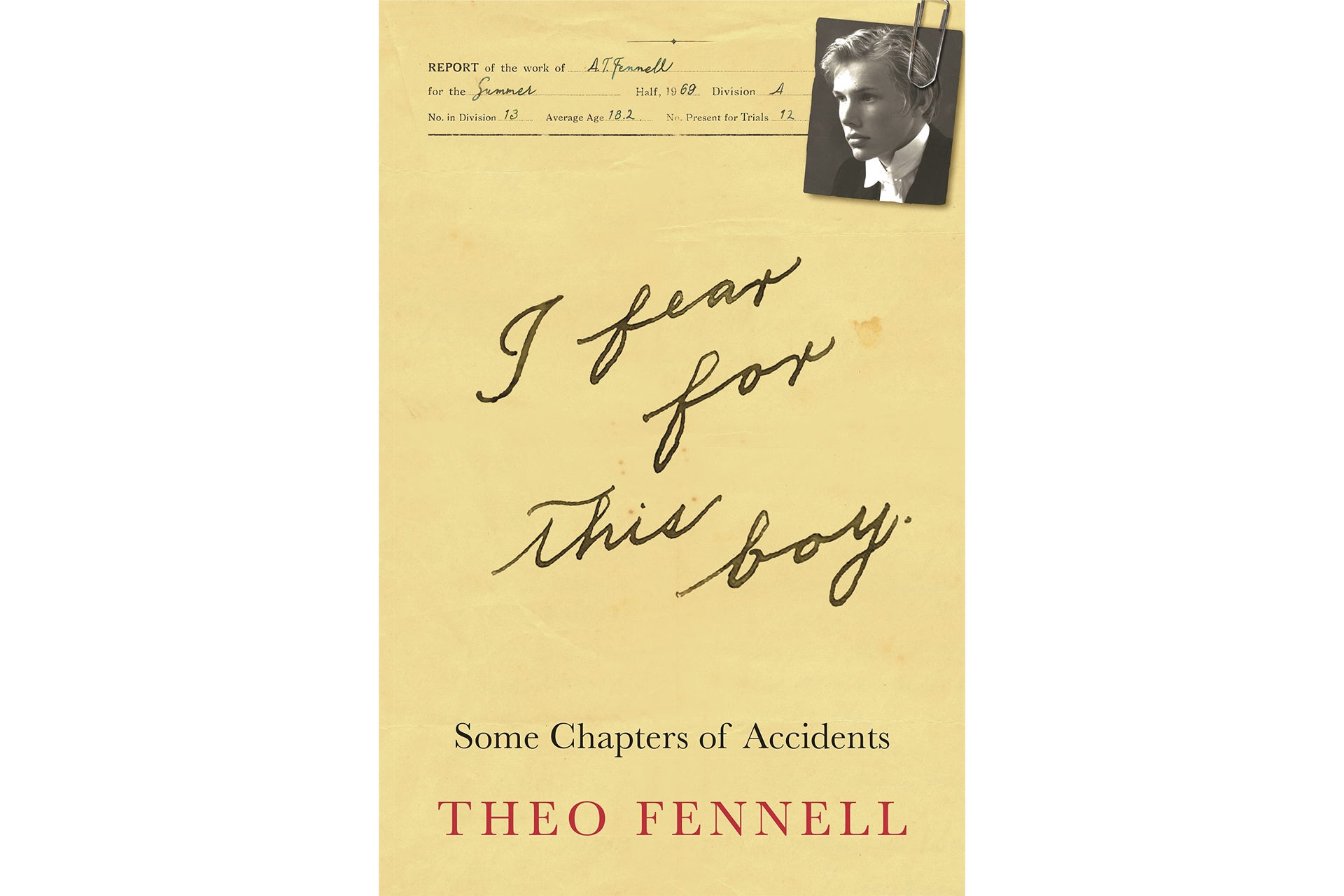

Theo Fennell’s new memoir ‘I Fear For This Boy: Some Chapters of Accidents’, recounts hilarious episodes from his formative years, as he journeyed from art student to successful jeweller to the rich and famous.

Listen to the Change Makers podcast with Theo Fennell

Theo Fennell on I Fear For This Boy

There is something distinctly larger than life about celebrated British jeweller Theo Fennell. It’s not just his height (at the age of 70 he still stands well over six feet) or his exuberant, colourful designs. It’s his very being; an inner exuberance and thirst for life, with all the excitement and adventure it has to offer.

And what a life he’s had. He’s captured a lot of it (although, he assures me, there is still plenty left for a second book) in his new memoir, I Fear For This Boy. Named after the words an old school master wrote on his school report, it’s a picaresque tale in 23 chapters, in which Theo retells the funny and often incredible stories have shaped his life.

There’s the time he unwittingly ended up on stage at the Royal Albert Hall, singing Feed The World alongside a litany of global rock stars. And the time he set up a jewellery-making workshop in derelict 1970s Hackney, only for his whole safe to be robbed by his light-fingered neighbours – who later tried to sell him back his pieces in the local pub. And then there’s the time in Texas… but you’ll have to read the book to find out how that ends.

Theo is a natural writer, and every chapter is retold with pace, wit, and a flair for storytelling, plus a healthy amount of self-deprecation.

Where did the idea for your book come from?

It was lockdown and I thought I’d write a book of some sort. My original thought was a novel, which is actually a very difficult thing to do. I was stumbling around like a fool, and I talked to a friend of mine [the novelist William Boyd] and he said, ‘you’ve just got to write. Think about something you know – all those incredibly dull stories you told me – and write them down.’ When I started writing in an episodic way, it became much easier.

I did two or three and showed them to my wife [the novelist Louise Fennell] who’s the world’s toughest editor, who put lines through saying things like, ‘pompous arse, nobody interested, boring, old fool,’ those sorts of things. She probably got rid of a third of each, which was a good thing. As it was lockdown we had the whole family at home, and a lot of them were writing [one of Theo’s daughters is the Oscar-winning filmmaker and actor Emerald Fennell].

You come from a family of successful writers. Did you feel any extra pressure to live up to their achievements?

I think you’ve got it wrong – they come from a family of writers.

The other reason I had for doing it – other than the fact I love having a project and I would have gone mad in lockdown if I hadn’t had anything to do – was that I was writing it for them. I have always wished my father had written down some of his tales because they always made me laugh. And they gave a terrific sense of what the mores of the time were and also what was popular, and the way people behaved, much more than any history book. It was meant as amusing anecdotes for them. When I finished, I printed it out for them to read, and they seemed to enjoy it and laugh. They came back with one or two wokeisms that had passed me by, which I of course changed.

You have some hilarious stories in your book. How did you get yourself into all these incredible scrapes and scandals?

I think in my youth I was game to try anything. If you’re up for anything you’re more likely to end up in scrapes. And I’ve never had much of an off switch, which was exacerbated by the demon booze, which had a radically exuberating effect. If you’re in that state of mind, things can happen that wouldn’t happen if you’d just gone home.

And I always found myself attracted to unusual people and naughty people, and that gave a set of certainties that made the bizarre episodes more likely to happen. If you have a natural aptitude for getting into odd situations, and if you find those situations funny at the time, which I nearly always do and did, then your reaction to them is very different to people who feel alarmed by them. If you find yourself in a set of odd circumstances you can either enjoy it and stick with it until it all goes pear-shaped, or you get so alarmed you forget the humour of the situation.

You have boundless amounts of energy and optimism in the book. Did you always feel like that at the time?

However morose I may have been from time to time, I think I always had enormous hopes that everything would turn out okay. The master who wrote ‘I fear for this boy’ obviously did see something of what would happen to me in the not-too-distant-future. But the time I always thought it would work out alright.

Obviously, we all have huge regrets but to harbour them and make them do anything other than teach you a lesson seems to me to be incredibly unproductive. And I think everybody does tend to spend far too much time worrying. I do worry but I always dislike myself for doing so because it does seem to be the most useless of occupations because very rarely does worrying do any good. When you look back at your youth and the things that worried you at 16, or 26, or 36, they don’t matter a bit now. You indulged so much fear and worry in a thing that really meant nothing. If only we had a way of knowing that when we were in the pit of despair. And for me, living in this country at this time, I couldn’t have been more blessed.

Do you think the modern world allows for like young people to have the kind of adventures you had?

A big difference was the lifestyle we had then. The communications were so basic 40 years ago, so if anyone wanted to take a photo of you misbehaving, they had to take out a great big camera. You didn’t have this constant Big Brother or constant communication. You talked to people and engaged with people far more than you do now. And you could walk into a bar and have a chat with someone, which I frequently did. You’d meet incredibly boring people, but you’d also meet incredibly lively and funny people, especially abroad. I think so much now is learnt secondhand, on the internet or whatever. People Google someone before they go for dinner with them rather than finding out for themselves.

How do you think that your adventures have shaped how you work today and how you design your jewellery?

What I do is fairly eclectic, and that’s partly because how and where I was brought up. My mind is like a garden shed or a very old attic. A thousand things go on in there, some of which is useful, a lot of which is probably not. But that idea of everything being interesting, and new things happening all the time, has been at the root of how I work and what I do.

You bought back your company last year. What are your plans for the future?

It’s been so long that I haven’t had it, that it’s been a really emotionally and practically fantastic thing. I do realise that now I have nobody else to blame, of course. But my plans are to do what we as a company, as a workshop and as a studio have always done best, and that’s to make jewellery that has some genuine sentimental and emotional heft. Because I think the best jewellery is not just very beautiful and beautifully made, but also has a weight for the person who wears it, which is why I love doing bespoke work. It’s like doing a portrait – it’s for nobody else.

I think there’s been a squeezing out of original design and craftsmanship by the globalisation of everything. For the first time ever, people who had the resources to do so, began to buy the same thing, which had never previously been the case for people who could afford to have things made for them. But I think that’s changed enormously, and lockdown was a huge catalyst, because it got people to start thinking about having things done and getting more involved the process. And that’s the direction I’d like us to go in.

And final words?

Joy and fun are very underrated currencies. And I don’t think you need to be a) hugely serious, b) rich, or c) successful to have fun.

I Fear For This Boy: Some Chapters of Accidents by Theo Fennell is out now, £25. bloomsbury.com ; theofennell.com