Interview: Vanessa Branson on A Surprising Family History

By

5 years ago

Showmanship, playfulness and risk-seeking run-through the Branson family tree

At a pivotal time in her own life, Vanessa Branson delved into her family history in a quest to find out more about her parents. The results make for a humdinger of a read, finds Marcus Scriven

Isn’t Life Wonderful? An Interview with Vanessa Branson

‘Whenever I see Indian friends now, I say: “We could be cousins”. A bond to a whole continent.’ Perhaps that bond explains the tiger-smile – prelude to delighted laughter – or even the silvered plimsolls, if not the signet ring and splendour of the family cheekbones, nor, quite, the loose-sleeved cotton top in bold black and white (‘designed by ArtC., a young Moroccan designer’).

Vanessa Branson has just ‘hammered back’ to Sussex from Shona, her island off Scotland’s west coast. It’s taken her six decades to learn of her Indian great-grandmother, a discovery all the sweeter for being made as she researched and wrote One Hundred Summers: A Family Story. It’s addictively good, a fusion of family portrait and personal memoir, born of a suddenly ravenous need to know more about her parents and ‘where their values came from – particularly my father’s’.

Eilean Schona, Scotland

The quest began in 2017, six years after his death at 93 and five years after the end of an intense but ill-starred marriage. She was 57, a ‘fulcrum’ age, she reflects, with her parents’ wartime generation fading away just as her children were starting families of their own.

The subsequent odyssey yielded a treasury of detail, some of it retrieved from the ruins of the recent past (‘My darling Clare, I’m so sorry to hear about Gerard…’ ‘… Don’t be’); some of it entrusted to her by cousins rarely seen, one of whom handed her a bundle of letters, on which appeared the plea: ‘Could anyone who finds these please burn them’ – a request which, mercifully, Vanessa ignored (‘Forgive me, dear Grandmother…’).

The Bucket List with Sir Richard Branson

In at least one instance, her intervention was just in time. ‘All these albums that my mum was going to throw away. They’re so beautiful’ – but not, she admits, entirely comprehensive: ‘Only the dogs are named.’

Vanessa Branson

Dissuading her mother – force-of-nature Eve Branson – from doing anything she’s set on is a UN-level triumph, even now. Her energy, writes Vanessa, ‘seems to increase with each conversation’. There’s no need to revise that verdict. ‘She’s 96 today. She’s got vascular dementia, so her short-term memory is a bit short. Very short.’ This proved a bonus when reading her the work in progress. ‘She never got bored of the same story,’ says Vanessa, laughing with adoration and acceptance. ‘It was lovely, the pleasure that it gave her. She’s on great form. Just the best – still. I think she’s just going to go on and on.’

It seems quite likely. Her own mother, Dorothy, known as ‘Dock’ – gymnast, cricketer, ice-skater, swimmer, squash and tennis-player – eventually expired at 99, though not before becoming acquainted with the latest Branson generation, despite claiming that she was ‘not really interested’ in her great-grandchildren (‘their genes are too diluted,’ she told a friend).

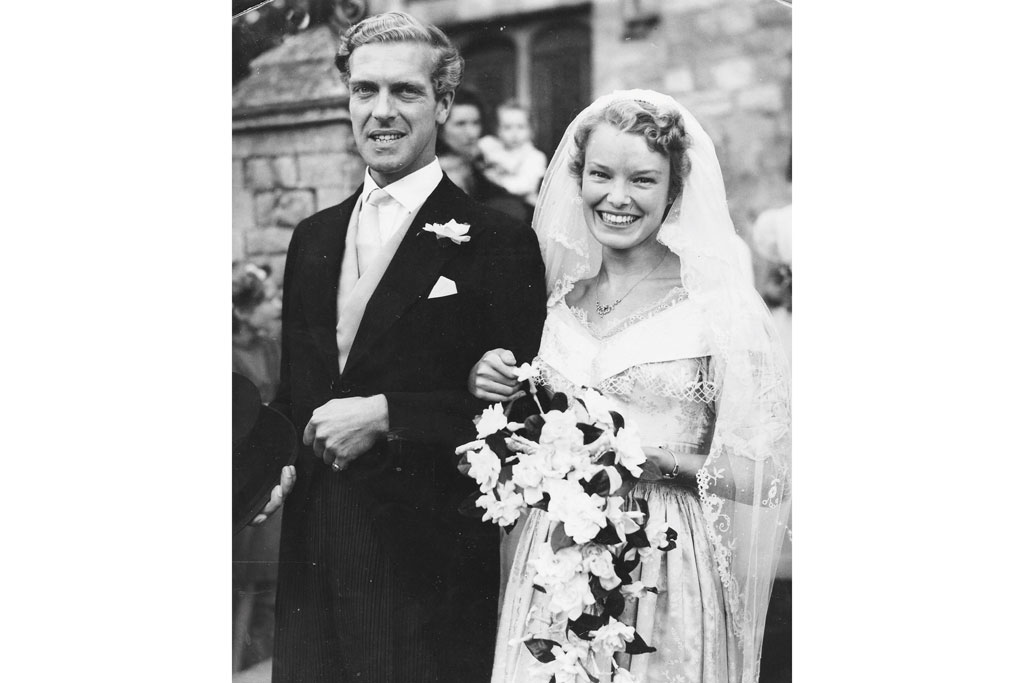

Vanessa’s parents, Eve and Ted

Dock comfortably holds her own with those from either side of the family – a suffragette (force-fed at Holloway) and Captain Scott (‘my great-grandfather’s first cousin’), as well as prelates, bishops and lawyers, a doctor and judge or two, including Vanessa’s paternal grandfather, Sir George Branson, successively of Wharfenden House, Surrey, and Bradfield Hall, Suffolk, plus a gardener’s boy who inherited a fortune, and at least one vegan (something of a pioneer, he harvested his food from municipal parks close to his Balham flat – his sole residence after he’d given away his Hampshire estate to his tenants, deciding that they were worthier of it than him).

Interviewed during the war, when his foraging talents made him a cause celebre, he voiced what surely must be the family creed: ‘A Branson,’ he observed, ‘never says “can’t”.’

Vanessa, Richard and Lindy (1966)

‘That Branson lot were just amazing, those brothers – incredibly energetic, clever and athletic,’ says Vanessa, speaking of Sir George and vegan Jim and two others. The same qualities – plus one more – radiate through her own generation. Like both her parents, and her siblings, Richard and Lindy, nine and five years her senior respectively, Vanessa is dyslexic – ‘a real thread running through the family’.

It meant that her father, initially destined for Eton, went to Bootham, a Quaker school in York, instead. Quaker philosophy – ‘everybody has good in them’ – entirely accorded with Ted Branson’s character. ‘It was so much my father’s thing. Dad always saw the good in everybody. When you were with him you just felt it.’ Hoping to become an archaeologist, he was corralled into the law by his father, the phenomenal if imperious Sir George.

Acting Royalty: Interview with James Norton & Vanessa Kirby

Looking out from Vanessa’s house on one of summer’s cinematic days – something of a Merchant Ivory set: sweep of lawn, oaks and copper beeches, walls of mellow brick, half-a-mile of track laced through the fields to the world beyond – the uninitiated might assume that this is what Vanessa and her siblings have always been accustomed to. They would be wrong. Ted’s Purdeys were heirlooms; the ‘family toothbrush’ wasn’t a figurative expression. Vanessa first had one of her own when she headed to boarding school (fees paid by a family trust).

‘He was never a dazzling barrister, never a QC; he found his niche being a stipendiary magistrate,’ says Vanessa, adding that, when home each evening to Shamley Green in Surrey, he began work again, this time for Eve’s fancy goods business. ‘He would never have been a successful businessman; he was too gentle. But he was so good with his hands. He could make anything.’

Lindy, Richard, Vanessa and their mother Eve

The children’s lives were guided by intuition and experimentation, and characterised by periodic bloodshed – once enthusiastically filmed by Eve on cine camera – and family fishing trips fuelled by alcohol and enhanced by engine failure. Perhaps they sensed that Ted had experienced worse, but he limited his wartime reminiscences to ‘stories about racing his tank on a horse’.

Richard was always ‘super-charged’, and Lindy ‘undeniably beautiful’, while the family characteristics could be summarised as playfulness and showmanship and an appetite for risk. ‘I think what defines us is… not being frightened,’ says Vanessa, whose accomplishments at Box Hill School included scaling the roof using dressing-gown cords as a safety rope.

48 Hours in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains – The Weekender

In adulthood, she has, so far, vaulted from cordon bleu cook and picture-framer to founder of the Marrakesh Biennale and owner of Shona (‘an act of lunacy’) and, as ‘accidental hotelier’, creator and co-owner of the most Instagrammed hotel in the world, El Fenn in Marrakesh, as well as championing artists from apartheid South Africa and – trickier – the Soviet Union, plus all manner of civic endeavour, and becoming mother of four adored children.

El Fenn, Marrakesh. Photo: Kasia Gatkowska

But she admits that the coronavirus outbreak has given her pause for thought, though not on her own account. ‘That [younger] generation have not dealt with it terribly well, even though it doesn’t really touch them. The amount of anxiety [they feel] worries me a bit.’

Her brother’s impending advance into space offers them the chance to reassess what risk really is. As does learning more about Ted, who, after his beloved sister’s funeral, explained to Vanessa why he hadn’t cried. ‘Ah, darling, I lost most of my friends in the war. I gave up crying at funerals a long time ago.’ She recently found his wartime diary.

‘Anzio. 120 days of being bombarded. They spent every single day as though it was going to be their last. Couldn’t dwell.’ Nor did he. ‘Isn’t life wonderful?’ was his undying refrain. Vanessa has it tattooed – discreetly in blue – on the underside of her right forearm.

One Hundred Summers: A Family Story by Vanessa Branson (Mensch)