The Visual Detox: What Do You See?

By

1 year ago

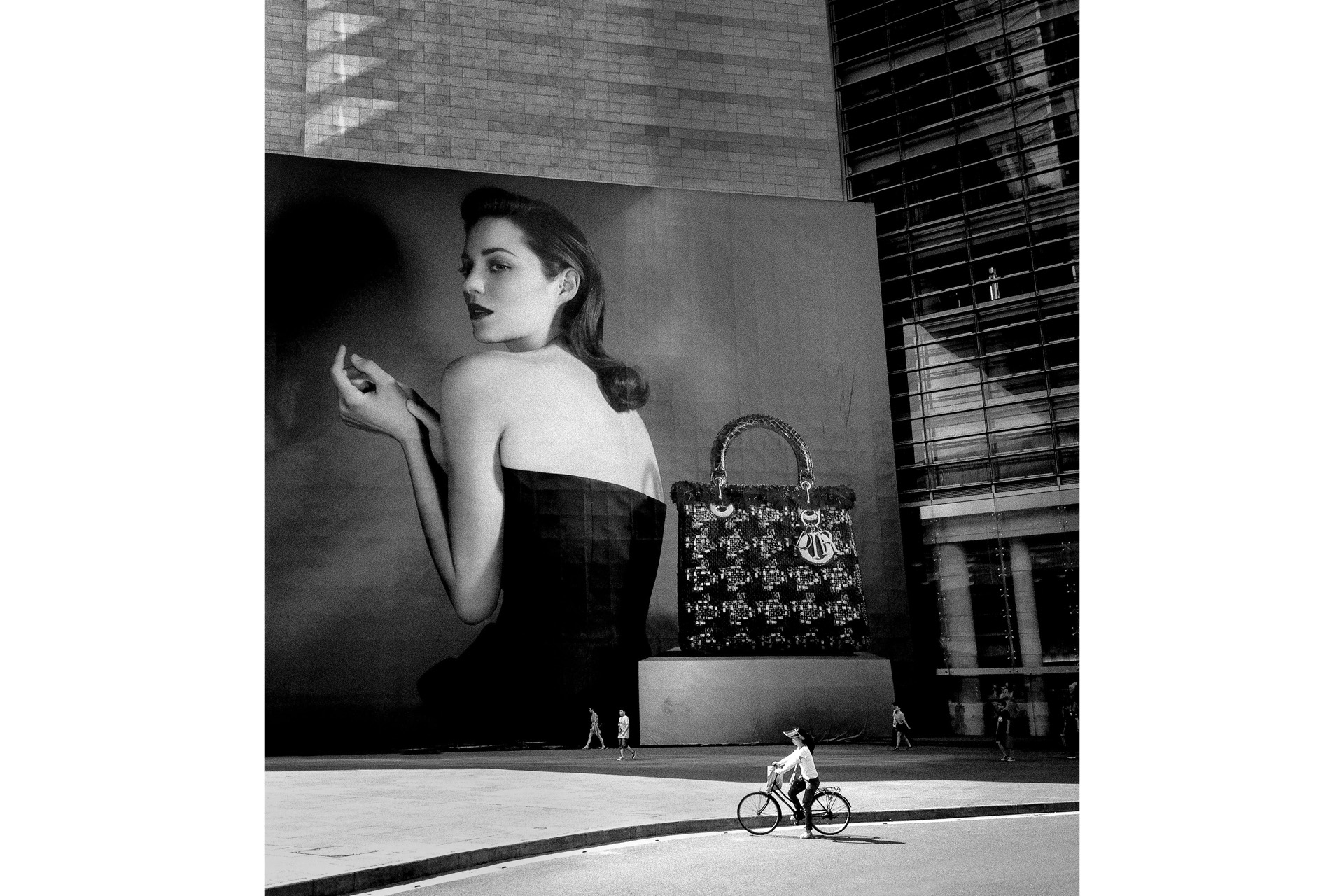

We see images all day, every day – many of which are adverts. What would happen if we flipped the narrative, and demanded more from our public visuals?

If you live in a city, it’s likely that you will see hundreds of commercial images a day, exhorting you to buy or behave in certain ways. It’s no wonder that our society has become so consumeristic. Flooding our public spaces with well-known wellbeing enhancers – nature and art – would help us reset ourselves as cogent citizens rather than passive data points. Are you ready to change your visual narrative?

Marine Tanguy: The Visual Detox

Close your eyes. Imagine your commute to work where you would encounter visuals narrating the importance of your mental health, the need to be inclusive and to lead sustainable lives. Imagine how much it would change your priorities. Would you be rushing to Zara to buy that discounted little top? Would you feel that your happiness lies in that fat and sugar-laden snack advertised to you? Wouldn’t you call a friend instead, or just daydream for a while, or give someone you don’t know a broad smile?

Open your eyes. Every day we’re surrounded by images, many of which are commercials. Coca-Cola spends on average $4.7bn a year on advertising, which means that you are likely to frequently encounter one of its ads on your commute. In the 21st century, we have become data points, pushed to sustain the gargantuan consumeristic society we have created. We forgot our need to be citizens, our need to share spaces, and to have valuable conversations where we live and work.

Images reach our brains 10,000 times faster than words. Most of us, 65 percent of us, in fact, are visual learners, meaning we learn most effectively via pictures, videos and diagrams. Yet we tend to receive imagery passively, believing that the endless onslaught of visuals doesn’t affect us. Would you accept someone shouting at you on the street all the time? Probably not. Yet images shout at us constantly.

Most advertising sells us the falsity that you can only be happy if you consume this product or buy into this lifestyle. It’s no surprise that when behavioural scientist Professor Andrew Oswald conducted a study between 1980 and 2011 on 27 countries in Europe, which compared our wellbeing according to our exposure to visual commercial imagery, he discovered that the more exposure to these kind of images we had, the more miserable we were. Given that over-consumption is fuelling the ongoing climate crisis, these images also aren’t conducive to the many changes we need to make as a society for the sake of the planet.

Mosaic Installation by

Arnaud Lapierre (2023), Christmas tree

commissioned by EC BID

However, once you are aware that you live in this visual world, there are so many actions you can take: endorse content you wish to see digitally and the brands that are respectful to you when advertising; demand more public spaces, more public art, and more common visual narratives.

Before founding my company MTArt, I researched the increase in wellbeing of residents and commuters after the implementation of two public art projects. The study found that 84 percent of people were willing to contribute more money via their taxes to fund more public art because of the way it promoted their wellbeing.

We cannot continue to say our society will change if the oldest language in the world, the visual language, remains the same. As artificial intelligence is on the rise, we also, more than ever, need to develop our visual critical thinking to fight against a sea of visual misinformation.

I tested teaching visual education at the school of my eldest son, Atlas. The children loved understanding how the daily visuals they saw made them feel but also how visual prejudice is built – using a certain composition or a certain colour – so subtly and yet so effectively. This was particularly true of the colour yellow, which they associated straight away with happiness. The children could therefore understand that the advert was making them believe they would be happy with this toy because it had yellow everywhere. We also looked at characters who were fully yellow, such as SpongeBob, and tried to understand the meaning of the choice of the colours that cartoons picked.

Very few of us can control the visual narrative that we consume daily, and therefore the advertising sector – and those with the money and power – can shape it as it suits their objectives. We have been made to believe it’s not our business – and yet these visuals shape who we are, our deepest desires and who we become. In Richard Easterlin’s happiness– income paradox studies, when asked what would be the ideal salary in 2011 in the US, pre-social media, people responded $60,000; ten years later it was $150,000. Not only was this down to inflation but the sheer number of social media images they were exposed to telling them they needed these extra things to be happy.

Estate; Another

Place by Antony Gormley (2005), a

public installation on Crosby beach,

Merseyside

On the flip side, nature and art always score highly when it comes to positively impacting our wellbeing, as has been proven by countless studies. Why, then, don’t we support the daily integration of both nature and art in the places we live and work, to balance the commercial imagery we are subjected to? Nature and art shouldn’t be something we are seldom exposed to. They are not a luxury; with the current mental health and environmental crises, they have become a necessity.

Words and visuals need to align; I am excited for more of us to open our eyes to a new reality where our visual world is one we have participated in, shaped and wished for. I am excited for artists to become a central part of our societies, to make us rethink our existence, dream and hope again.

My English hero, the 19th -century social reformer Octavia Hill, pushed for an amendment many moons ago to make sure that our parks didn’t get destroyed, which led to the founding of the National Trust, and the protection of Hampstead Heath from development. Now it’s time to recreate the same movement for public art projects and to build our own visual narrative that represents us all, protects our mental health, and empowers us.

Marine Tanguy

Marine Tanguy is the founder of B Corp artist agency MTArt. Her first book, The Visual Detox: How to Consume Media Without Letting it Consume You, is out now (Square Peg, £16.99). waterstones.com