Why Did 1,600 People Buy A Bit Of A Stamp?

By

1 year ago

How fractional investment became the thing

Fractional investment in rare collectibles is gaining in popularity. Tessa Dunthorne investigates the trend.

A Slice Of The Pie: How Fractional Investment Became A Thing

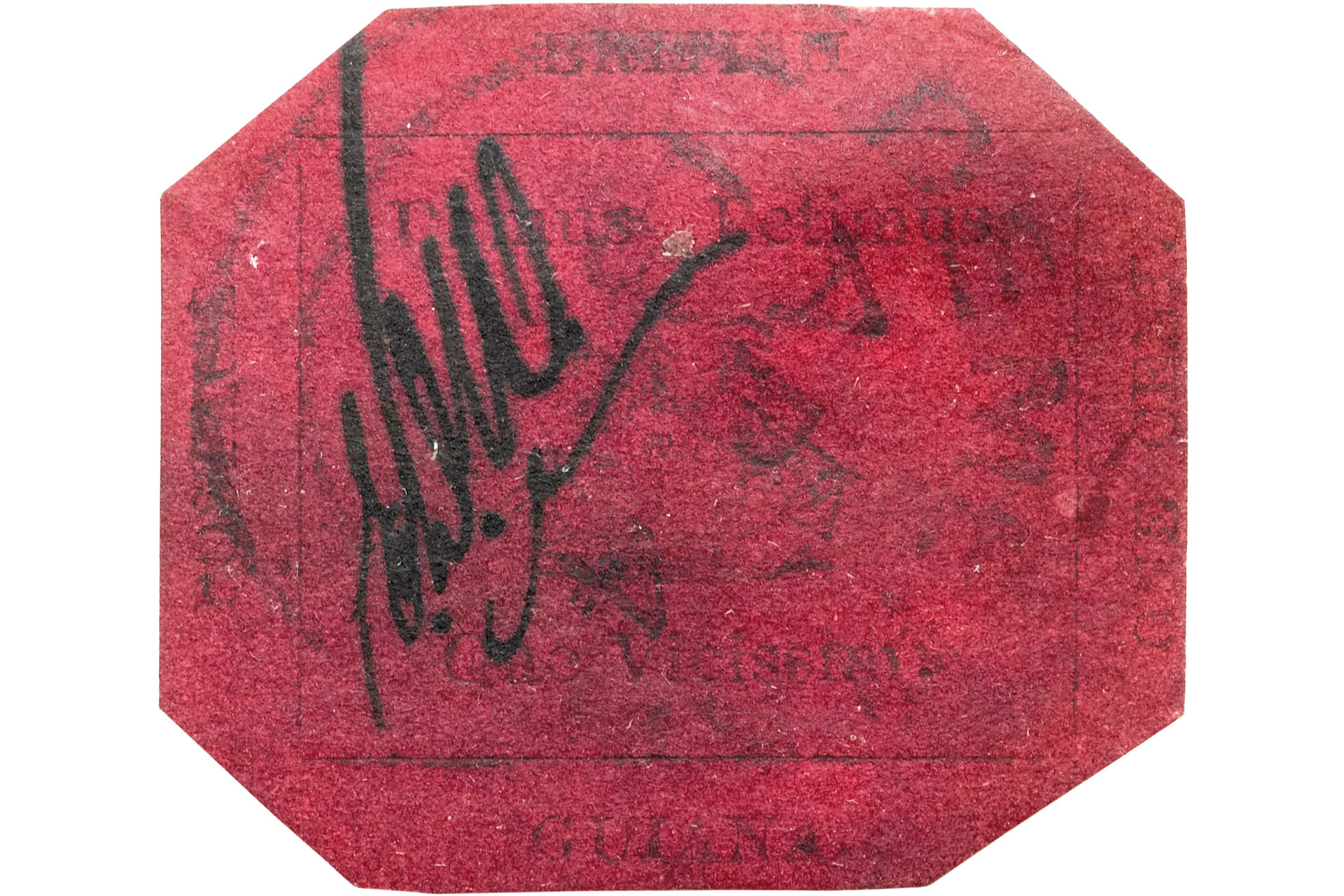

It might be tiny, but this stamp is the most expensive item in the world by weight. The 1¢ Magenta is among the most famous in the world – if you’re into that sort of thing. Not because of a manufacturing error (which is why most stamps’ values soar) but because it’s a true one-of-a-kind. And, until 2021, it had only had 12 owners in its history.

‘Now it has 1,600 owners,’ says Aaron Carter, managing director of Showpiece, a platform that allows users to invest in rare collectibles.

Collectibles are having a moment, particularly as a fashionable arm of your investment portfolio. The late American investor David Swensen was credited with legitimising the practice – his work demonstrated that by aggressively splitting your assets across alternative funds, you get the best return on investment. Rare items – whether art, limited-release trainers, or indeed the world’s most famous stamp – don’t respond to the stock market, so may retain value when your traditional portfolio is in the red. And, says Aaron, ‘It’s more interesting than buying a few quid of a company on the FTSE index.’

In fact, according to Deloitte, 85 percent of wealth managers agree that art pieces (and similar collectibles) are important additions to any balanced portfolio. Which is great – if you’ve got the readies to invest in rarefied artefacts.

However, what if you want a piece of the action for a fraction of the price? The 1¢ Magenta is just one example of how fractional investment is gaining traction, providing its 1,600 new buyers the chance to buy a slither of it from only £100. And this practice, according to Charlotte Stewart, MD of MyArtBroker, is ‘a zeitgeist’ that’s only growing.

‘It’s not been around for ages, but there’s a huge variation on what people fractionalise,’ she says, ‘from fine wines and whisky to James Bond’s underpants and even a piece of cake from Queen Victoria’s wedding…’

Masterworks, the US based art-market that sells visual media by the slice, is the biggest platform. To date, it self reports to have raised ‘over a billion dollars’. When Scott Lynn founded it in 2017, he’d come to it as a collector himself. ‘I’d been collecting art for a decade,’ he says, which inspired him to ‘create an investment vehicle for art, so that millions of people who didn’t have millions of dollars could include it in their portfolios’.

The average user attracted to this kind of service, he says, is a high-net-worth individual who earns at least $100,000. They’re of all ages – ‘we have investors from their 20s to their 60s’ – and they want to diversify beyond stocks and shares, aiming for about a five percent allocation of their portfolio to be in paintings and prints. They’re global too: ‘There’s definitely interest among wealthy Chinese individuals and the Korean market.’

But it’s not just about the investment’s financial performance, according to Aaron. ‘We’ve found that many people who purchase investable assets don’t necessarily expect to make profits that outperform the FTSE or S&P 500,’ he says. ‘If they get back what they invested and it derisks some of their portfolio – and they get an experience out of it – they chalk it up as a win. For our users, the fractionalisation is about the passion of ownership.’

The 1¢ Magenta is a great example. Stanley-Gibbons, the world’s largest stamp dealer, chose to sell the stamp via Showpiece in 2021; the sale attracted thousands of people willing to invest. Most were passionate about the stamp itself. ‘The 1¢ is the only one the Royal Collection doesn’t have. It’s also the one that everyone knows will never be in your stamp book,’ says Aaron. ‘There was a 92-year-old who had been collecting stamps since he was a boy. For him to be able to come in and own that little piece – it was something quite magical.’

There’s another reason that fractional ownership may spark passion in would-be buyers. ‘When owners pop into our place on the Strand, we can show them the item they own,’ Aaron says. ‘As long as our users own various items, they’re out on public display.’

Why is this important? ‘Museums are struggling,’ he says. ‘Foot traffic is falling year-on-year. They’re cash-strapped, and can’t afford to acquire apex assets and keep them on public display.

‘Some public museums no longer display items owned by ultra-high net-worths for fear of being seen as a shop window. Museums and galleries can’t compete for assets anymore – the only way to keep these items in the public realm is through fractional ownership, because benefactors alone can’t sustain it anymore.’

Collective ownership of assets is a vehicle that can facilitate common access of goods, then. ‘I definitely think that’s right,’ says Scott. ‘Our artwork is either lent to museums or kept in storage, with efforts to display as much as possible. A lot of culturally significant art goes into private collections and is never seen again. Fractional ownership allows for pieces to be displayed publicly.’

As core government funding for arts councils has decreased in the past few years – by 18 percent in England, and up to 66 percent in Northern Ireland – this kind of action might be necessary. Many of Britain’s major cultural institutions have been sounding the alarms over their ability to invest in their collections – Woking’s the Lightbox told The Arts Newspaper this year that council funding’s sudden drought meant it was losing about a third of its income – and so it’s no real surprise that the solution offered by platforms such as Showpiece and Masterworks is appealing to philatelists.

But as an actual asset, fractional ownership is not guaranteed to be a surefire investment. Charlotte says she tends to advise caution on collectibles without a solid investment background – they only buy and sell those which have at least seven years of data to follow. ‘It’s helpful to know what the artwork has done across a decade or so,’ she says, ‘because the whole thing hasn’t been around for ages. That’s actually one thing Masterworks do really well, for example – how much data they’ve got on the performance.’

And, more widely, there’s been a slowdown in the luxury industry that’s affecting the entire investable asset market. Christie’s recently reported a 22 percent drop in auction sales; the value of a collectible is ultimately dictated by the upper limit that a buyer is willing to pay, so this spells trouble. Fractional investment platforms aren’t isolated from this because their users have smaller stakes in the game and, in fact, may face hidden management fees in final sales, which affect their eventual return. ‘Transparency is essential,’ says Aaron. ‘The breakdown of costs and expected returns must be straightforward with no workarounds. That isn’t always the case.’

This is a key reason one end-user – David, 67, a retired GP who invests in fine wine for resale purposes – wouldn’t consider fractional ownership. ‘As soon as you go in with a company, you pay management charges – and you don’t have control over the asset.’

And though a drive for community benefit is all well and good, he sums up the final reason that it may not appeal: ‘If you own the asset – in my case, wine – and it all hits the rocks, you can always drink the stuff.’