Can Coffee Be Saved From Climate Change?

By

9 months ago

Maybe – with synthetics, new beans and better farming

Coffee is under threat from climate change. Scientists and farmers all over the world are racing to find alternatives to save both our morning drink and the livelihoods of many. Is there a brewing storm on our hands?

The Future Of Coffee In Climate Change

‘We’re seeing lower yields,’ says coffee crusader Pacita Juan. ‘Climate change is drying up trees growing in lower elevations. Without rain, they’ll die. We now water them. The effects of climate change are going to be detrimental not just to coffee – but all crops in general.’

Pacita is calling me from the Philippines, where she is the president of its Coffee Board. Over the past decade, they’ve noticed their trees suffering from global heatwaves, and it’s worrying them. What’s the future of the crop? And if coffee is under threat, what does it say about the wider state of our food systems?

Coffee berries © Getty Images

Coffee grows as a fruit across over 40 countries along the equatorial tropics of Capricorn and Cancer – the ‘bean belt’. The biggest producer is Brazil, followed by Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia and Ethiopia. The Philippines, by contrast, is a niche grower state. It doesn’t represent as large a proportion of its economy, so if the crop fails, the effects are less extreme. A nation such as Ethiopia, though, where coffee is its biggest export? That’s disastrous.

‘Coffee is highly sensitive to changing climates, and this crop is highly threatened,’ says Dr Aaron Davis, head of coffee research at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ‘Our two main coffee crops, arabica and robusta, have been doing great service since the early 20th century, but farmers are now reporting serious issues growing these species.’

Wondering how to live more sustainability? Look no further

The Philippines, thanks to its mountainous, volcanic terrain, is uniquely suited to grow four different species of coffee crop – arabica, robusta, liberica and excelsa – which allows it to observe the impact of climate change across various growing conditions. The fact that it grows four species is unusual; arabica and robusta account for 99 percent of the coffee produced worldwide. Arabica, typically cultivated in east Africa and South America, thrives only within a narrow range of environmental conditions; it begins to suffer from heat stress above 40˚C. Robusta grows in wet, tropical Africa and Asia, and handles slightly more heat than arabica, but is a thirsty plant that – with droughts on the increase – now needs irrigation. The latter also tastes worse; it’s typically kept for instant coffee.

Coffee trees in the Philippines struggling in the heat. © Pacita Juan

Today, even in a moderate warming scenario, according to CarbonBrief’s commodity profile, Brazil stands to lose up to 80 percent of its coffee-growing land. Worldwide, it looks to be about half. And it’s not just the rising temperature that’s at play; the fact that we cultivate only two species of coffee invites trouble. Limited genetic variety means this crop has little resilience to environmental threats (coffee leaf rust disease and invasive pests). Farmers ideally would breed out these issues, but 60 percent of the more than 120 wild coffee species are already at high risk of extinction.

It’s to the wild, then, that researchers head with urgency. The clock is running out for coffee – and this is how we save the bean.

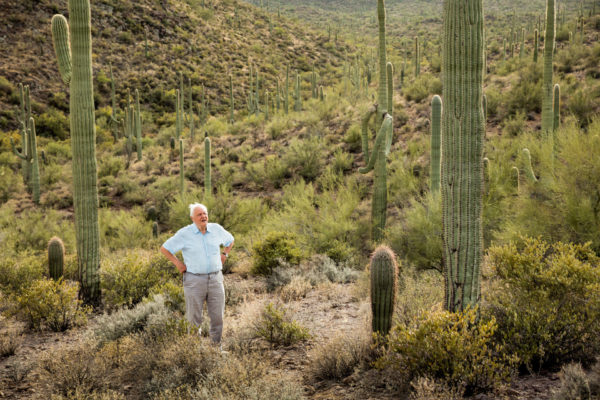

I first met Dr Aaron Davis two years ago at a talk at Kew. The research centre had organised a series on the future of our food, arguing that our planet was going to struggle to keep growing foodstuffs in the way it had for millennia. The talk I remember with total clarity was Aaron’s. He stood in front of us – tanned from fieldwork – and said our coffee was dying and that there was probably no going back, but that there was still hope. His globally spread team was doing the work of finding alternatives, new beans that could survive a changing world.

When I talk to him again, he is just back from Borneo. ‘We’d flown to Kuching and then headed north into the remote river valleys where people were growing liberica excelsa,’ he says.

His career has been spent in the field seeking out these remote plant species. ‘At the beginning, I worked in traditional botanic research,’ he says, ‘but then I got interested in coffee and climate change, and how this would affect both wild and cultivated species. I began to wonder whether we could use the knowledge we’d built up on wild species to see if there were any alternative species that are more tolerant of drought and high temperatures.’

Liberica is one of a few species that Kew is studying in the bid to find a climate-resilient bean. It was, according to Aaron, almost forgotten: ‘At the end of the 19th century, liberica was a global commodity, but then farmers discovered robusta, which they began to prefer to grow, so the former fell out of usage at the global scale, only cultivated on a small scale in areas of Southeast Asia – until recently.’

Why liberica? Simply put, ‘It’s a big, thuggy plant,’ says Aaron. Its deep roots and thick, fleshy leaves gives it an environmental resilience that other species lack. Pacita agrees. ‘We call it the “wild boar” species here because it’s so thick,’ she says. ‘It survives really well because it grows under the shade of trees – where it’s about five degrees cooler.’

‘And we’re developing excelsa coffee in Uganda,’ Aaron says, ‘it’s a related species to liberica and very tough. We haven’t got the data yet to evidence that it’s drought- and heat-tolerant, but it’s more so than robusta and arabica. We’re still a little circumspect though, because we can’t yet prove it.’

Then there’s stenophylla, a species that’s been ‘rediscovered’, having not been seen in the wild since 1954. ‘It tastes like arabica – has a high-quality flavour profile – but it grows in much warmer conditions and through dry seasons.’ Tasting panels with Q graders from Nespresso and Jacobs Douwe Egbert back this up.

Wild coffee species offer a potential lifeline to the coffee industry. It might mean our supermarket shelves will look a bit more varied – think of the choices of teas we already enjoy. It might also mean scientists have a starting point for breeding resilient hybrid plants. ‘It begins by providing options for farmers,’ Aaron says. ‘They need a choice because an arabica farmer in the future is unlikely to be able to grow robusta – it has different environmental needs – but they might be able to switch to excelsa.’

These aren’t magic bullets though. Excelsa and liberica have lower yields than our favoured cultivated coffees, and represent less than one percent of what’s grown globally right now. It’d be a big ask to make a complete jump to new beans – and, at lower yields, with less profit opportunity. According to Forbes, 80 percent of coffee farmers are living in a cycle of subsistence. With all this demands, some farmers might opt out of the game entirely.

‘There will be less coffee producers [in the future], which will be an issue,’ says Aaron. ‘It’s not just about climate change. The younger generations do not want to do what their fathers, mothers, grandparents did. There’s a demographic shift coming.’

The other bad news, then? There’s no doubt our cup of joe is about to get more expensive. ‘With fewer people growing it on smaller profit margins and with antagonistic influences like climate change, the price [of coffee] will go up,’ says Aaron.

‘The weather is punishing, it’s more difficult to get coffee from the farms,’ Pacita says. ‘Prices have already gone up. Robusta is crazy right now – I haven’t seen prices [like that] in my whole career. It’s through the roof.’

With all this in mind, talk abounds around alternatives: synthetic coffees – the likes of Atomo’s beanless espresso. ‘Production starts by identifying the compounds in other farm-grown ingredients that contribute to the distinctive flavours and aromas of coffee,’ says Atomo chief operating officer Ed Hoehn. The brand claims to recreate coffee so thoroughly that, in blind taste tests, the drink is indistinguishable from the real thing (the company identifies the beverage as a ‘real’ coffee but still a product distinct from the ‘traditional’ ones).

Atomo’s synthetic ‘coffee’ pips

And these coffees have the added benefit of being significantly less carbon-intensive than traditional ones. (HowGood verifies that Atomo’s drink is 83 percent lower in emissions using 70 percent less farmland.)

The relationship between coffee and the climate isn’t one way either: coffee has significant impact on the planet. According to UCL, ‘Growing a single kilogram of arabica coffee in Brazil or Vietnam and exporting it to the UK produces greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 15.33kg of carbon dioxide on average’. A single cup of the stuff requires 39 gallons of water according to Unesco Institute for Water Education – which will rise as more coffee farms require irrigation. Given the environmental impact of the drink, is it time we start thinking of coffee like we do meat: lowering our consumption and mixing alternatives into our diet?

‘I think synthetic coffees will have their place,’ says Aaron. ‘Some consumers will say, “Yeah, that’s fine, as long as it tastes like coffee and has caffeine”.’

Should we be okay, though, with taking coffee out of the hands of grower-producer nations? Even putting aside the economic importance of the crop for the lives of those in the ‘bean belt’, this type of farming makes up part of the cultural heritage of these nations. In Colombia, the coffee producing regions of Caldas, Quindio, Risaralda and Valle del Cauca are World Heritage sites.

To save our coffee crops, then, there’s a need to future-proof existing farmlands. Coffee plants enjoy a lifespan of more than a decade and establishing new crops takes three to four years. Before we’re ready to breed new species, we need those that exist to keep on producing fruit, lest they be wasted.

Some producers – not just small, independent ones, but large ones like Nespresso – are already doing this through regenerative farming. ‘Regenerative agriculture has the potential to both reduce agri-food emissions and leave the land in better condition than how one finds it,’ says Mary Childs, Nespresso’s UK sustainability lead. ‘Our aim with our regenerative programme is to increase both the yields and quality of our coffee. And for us, sustainability and quality are things that go hand in hand.’

Restoring soil (a key part of regenerative farming) helps adapt the crop to handle unpredictable weather conditions, such as heavy rain, so it’ll be less at risk of erosion. ‘We’re also installing windbreaks to make the plants less susceptible to extreme weather events,’ says Mary. Then, there’s work to be done planting trees around coffee regions to sequester carbon and improve biodiversity, which further supports the soil.

Going back to Pacita’s point, climate change will be detrimental to coffee and, indeed, many other crops – if not all of them. Coffee is perhaps one of the canaries falling silent in this planet-shaped coal-mine of ours. But there’s hope – adaptive measures, alternative drinks and considered crops – and how we save coffee might just form the model for how we do agriculture in the future.