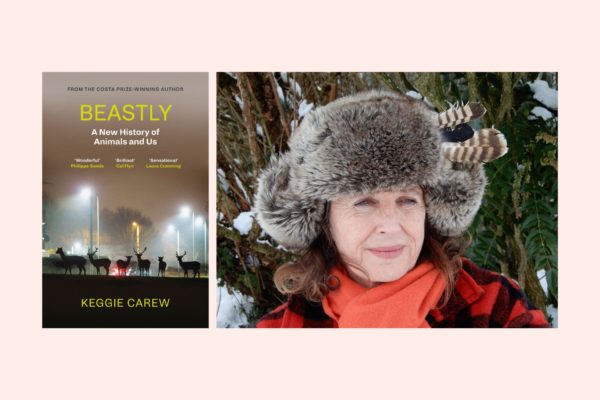

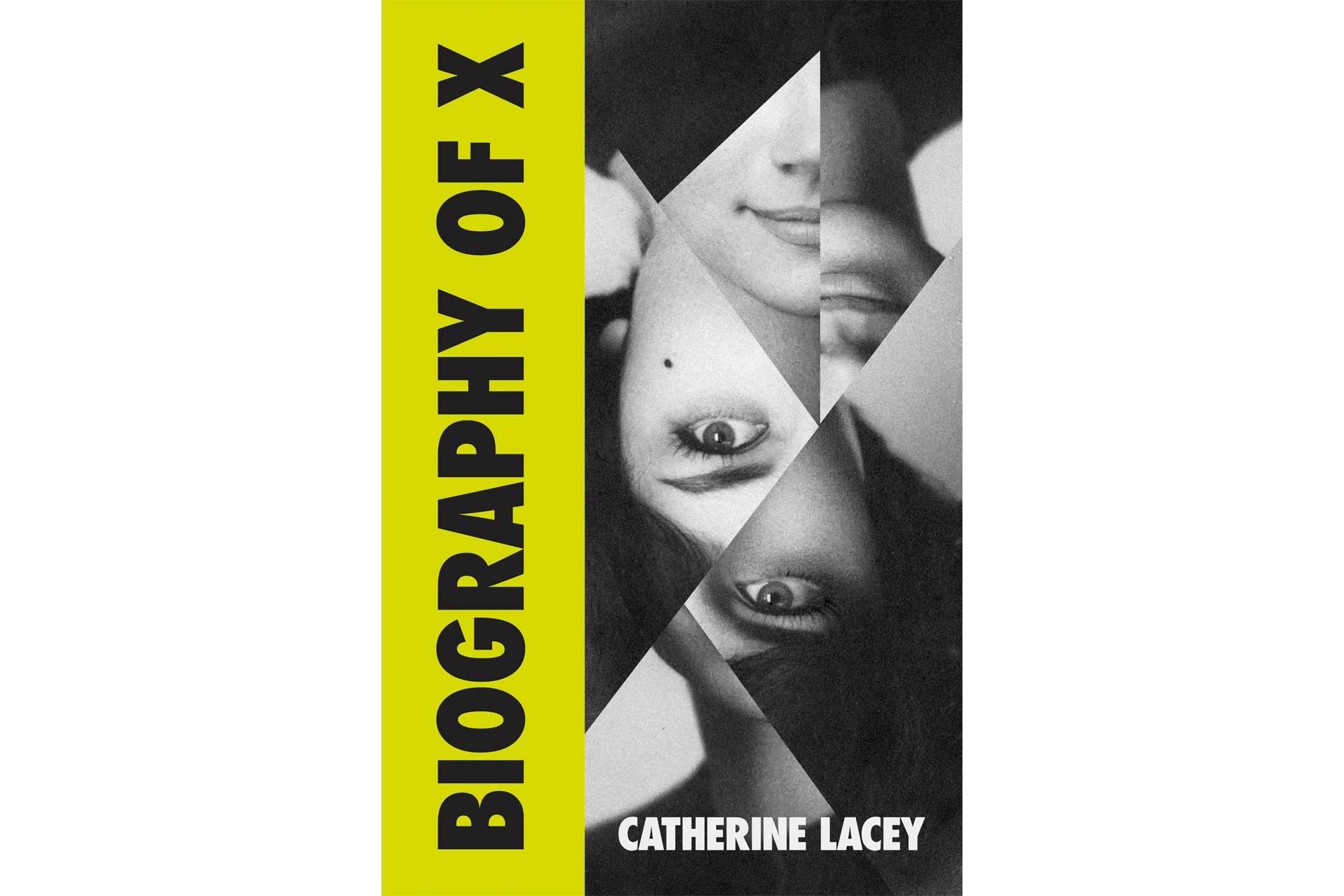

C&TH Book Club: BIOGRAPHY OF X by Catherine Lacey

By

2 years ago

Rewriting American history to centre a queer love story

In May’s Book Club, Catherine Lacey tells Belinda Bamber why she set her broken love story in a dystopian, last-century America.

C&TH Book Club: BIOGRAPHY OF X by Catherine Lacey

Belinda Bamber: You were one of Granta’s 2017 Best of Young American Novelists and The Biography of X has been hailed as your Big American Novel, set in a fictional dystopia. Did it feel like a BAN, or did you write from a more personal place?

Catherine Lacey: I always write from a very personal place, though I don’t always know what I’m writing about until it’s done, or long after it’s done. It was clear to me from the start that I wanted this to be a story of one woman trying to comprehend another, someone she loved and was harmed by, but I didn’t want the work to be burdened by the constricting forces a queer couple would have to live with in the mid-20th century in the States – so I rewrote American history to give these characters a break. That was really the only reason American history was rewritten.

BB: X is like a ruthless, shapeshifting Greek goddess unleashed on the human world. Any role models?

CL: I think she’s bigger and more ridiculous and flawed and unbelievable than any of the people who inspired her. Lou Reed’s recklessness, Susan Sontag’s intellectual capacity, David Bowie’s stage presence, Cindy Sherman’s power of disguise, Adrian Piper’s contrarian power, Fleur Jaeggy’s reclusiveness – such a person can’t really exist except in imagination.

BB: Why did you write it as a biography?

CL: Part of what I love when reading a biography is learning about the friendships and relationships the subject had with other creative people. This one is written by someone who is grieving X and dissociating by writing about her. She encounters situations she’s unprepared for – the ruins of a fascist theocracy, for instance. My intention was to make the novel seem as much like a biography as possible, albeit a biography being written by someone who is grieving and dissociating into writing. She encounters a lot of situations she’s unprepared to encounter – the art world, or the ruins of a fascist theocracy, for instance.

BB: And why did you backdate the story to the mid-20th century rather than pitch it in the future?

CL: I wanted X to be in conversation with writers and artists of that time. Setting a book in the future inherently makes a statement about the present that I’m not really interested in making right now.

BB: The universe you create around X is so detailed – even down to the mix of real and fake footnotes and photos. Did you enjoy writing it?

CL: I always enjoy writing! There’s this idea that if it’s not fun to write, it won’t be fun to read. That may not always be true, though. And maybe ‘fun’ isn’t always the right word for it. But a novel is sort of a long logic puzzle, in some ways, and I find it satisfying to solve such a puzzle.

BB: To what extent is the book an exploration of sexual and gender identities?

CL: The various and more specific words and descriptions we have for these different sexual or gender identities are just words – the identities have always existed, they just haven’t been visible in the mainstream. It is very human and understandable to want to be seen as the person you feel yourself to be, yet as Walt Whitman wrote in 1855, ‘Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)’ It’s tricky, but I think necessary, for a person to find a way to life that feels authentic to their particular multitudes. Those who don’t feel that tension don’t seem to understand the exploration. There’s a reading of this novel that could find some connective tissue between X’s many identities and the cultural moment we find ourselves in – one in which many people want to safely express who they are and other people seem alarmed and threatened by such expression.

BB: You have a gift for droll dialogue. Do you take a notebook to cafes, and which writers make you laugh?

CL: I really enjoy the kind of moment in the writing process after I’ve spent a while setting up a world and characters and I can just go in and listen to them speak to each other. I don’t intentionally eavesdrop in cafes but I did a lot of that when I was in my late teens. Lots of other writers make me laugh – Lydia Davis, Lorrie Moore, Fleur Jaeggy, Franz Kafka, Thomas Berhard, Gabrielle Lutz.

BB: Tom Waits, Susan Sontag, David Bowie and other famous figures make guest appearances in the story. Any comeback?

CL: Up to a point, you can quote from any written work without permission and as long as you credit it, you’re fine. (There were lawyers who cleared everything, which is pretty typical when you write a work of nonfiction.) The writer David Shields, who has made entire books from quotes from other people, encouraged me not to print the credits. I’m not that sort of writer, so I printed the credits.

BB: Are any of the ‘crazy-famous-people’ stories, like Connie sleeping under the grand piano, gleaned from real-life anecdotes?

CL: That one’s not real, not to my knowledge, but it seemed in keeping with Connie (perhaps) so it’s in there. I think every time I took something true and changed it for the novel, I wrote a credit for it in the 13 pages of endnotes.

BB: When did Biography of X first start to form in your mind? And did you always have that title?

CL: Often I don’t know the title of something until I’m done but in this case I had the title early on and I didn’t really question it. I think it does the job. To some degree a writer has to resign themselves to the limits of a title – it’s always inadequate.

BB: This is your longest novel and the wealth of material is phenomenal. Endings in art, as in life, can be difficult – what about this one?

CL: I don’t usually share something with anyone until I feel like I’m done – it’s just a feeling, barely perceptible but undeniable, that the book is done. At a certain point a book can’t really improve, it can just change, and once I’m there I usually give it to my agent, Jin. She is my first bullshit detector and she usually has notes that I always incorporate. Then it’s on to my editors, Jackson and Eric, who get more granular with me. They both understand my aims as a writer and they help me achieve those aims more directly.

BB: Do you remember your first story? And when did a career as a full-time writer feel viable?

CL: One of the first stories I remember writing was a retelling of Little Red Riding Hood. In it, there’s no wolf, no grandmother, no wood. A girl gets in a car and drives away. I suppose it felt satisfying to write because I always did it, but I always assumed I would have jobs. I’m from a traditional part of the states and my father (joking, but not joking) told me I would need to get married to someone rich if I wanted to write full time. I assumed, at least, I would have other jobs. I worked as a cook, a secretary, a tutor, a personal assistant, and at one point I started a cooperative business with several others. It turns out I write better when I get to focus on it, and various people and entities have made that possible for me. But I never had the hutzpah to assume I would be a full-time writer. And I always assume it’s about to come to an end.

BB: Ideal writing day? And do you edit yourself while writing or redraft later?

CL: I’ve been somewhat nomadic for the last two years, mostly by a matter of circumstance, so I’ve gotten pretty far away from routine. At one point I was living in a small house near the ocean and I would write for a while in the morning, then go to swim in the ocean. That was pretty ideal. I both edit as a I go and do huge revisions that involve lots of throwing things away. I think the ideal days for writing also involve a lot of things that aren’t writing—cooking, walking, swimming, reading. On a good day I’d do at least some of those things.

‘Biography of X’ by Catherine Lacey is published by Granta (£18.99), granta.com.