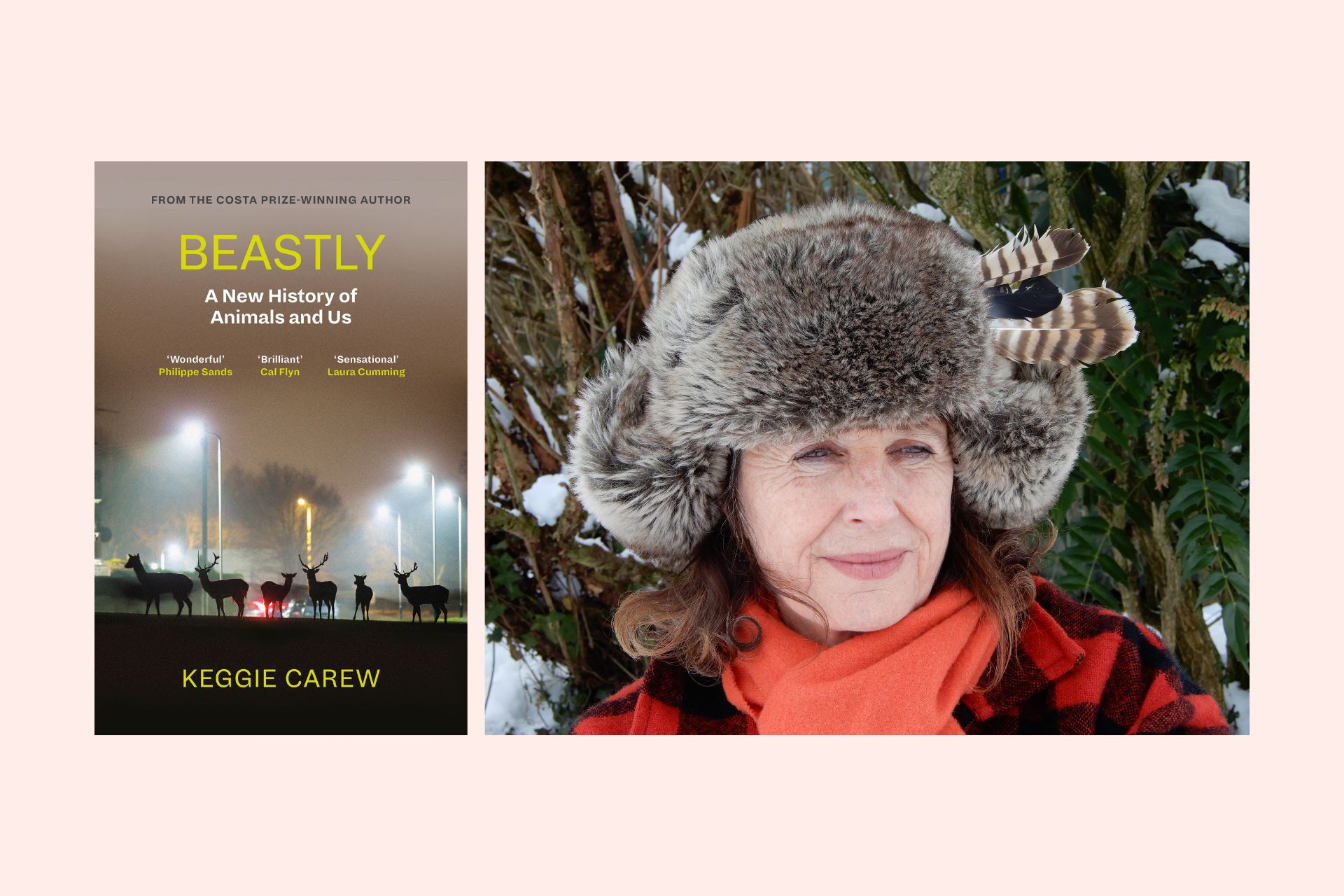

C&TH Book Club: Beastly by Keggie Carew

By

2 years ago

Belinda Bamber chats all things animals with Keggie Carew

In April’s Book Club, Keggie Carew, author of Beastly, tells Belinda Bamber about her heroes and villains in humanity’s ancient and extraordinary relationship with animals.

Beastly by Keggie Carew – The C&TH Book Club

Belinda Bamber: Beastly covers 40,000 years of our relationship with animals, and its gestation started when you were sent ‘a photo of a boar, a candelabra and a girl’. It’s a very different book to Dadland, which won you the Costa 2016 Biography Award. Tell us more.

Keggie Carew: My agent sent me the photograph a few years ago. Centre stage, in a dining room crowded with 19th century clocks and lamps was a giant boar standing on her hind legs with her snout on a thick oak-ring table. A girl was scattering crumbs from a loaf of bread. The candelabra was precariously alight. The time was 12 o’clock. It was like a fairy story. Outlandish, yet somehow natural. I stared and stared, and it cast a spell on me. Two years later I was there. My face baffled against the glass pane of a deserted lodge deep in Poland’s Białowieża Forest, peering into the very room. This was the home of Simona Kossak, the zoologist who studied the wild animals who lived in the forest around her. Here was the lodestone for what would become Beastly, this paradoxical and complicated story of animals and us.

BB: Do you see that emblematic photo any differently, now you’ve finished writing the book?

KC: That is a very perceptive question, because I absolutely do. I see it now as the parable it has become. The clocks tick. The light flickers. Time is running out. The mighty boar and the girl break bread. Our home is shared. Our sustenance is shared. Life supports life. It is time to rethink our relationship with the creaturely world.

BB: Beastly is a succinct title: it describes our own ‘beastly’ humanity as well as the extraordinary variety and ingenuity of animals. Which creature in your research most astonished you?

KC: Yes, Beastly plays on all those things – that we are indeed all beasts. Nothing wrong in beastliness, aside from the way we use language. That the word has pejorative connotations is telling in itself. So, aside from everything about cephalopods, the mites who live in the ears of noctuid moths astonished me. Because although they break the tympanic membrane, which deafens the moth’s ear, they never migrate to the other ear. That would not do for a moth who needs to detect the echolocation calls of hunting bats, nor for the mites if the moth becomes prey. So, by the never-ending wonder of the world, the mites send scouts across to the clear ear to lead any stray wayfarers back home. Humans could take a lesson from these mites.

BB: Which extinct creature would you bring back to life?

KC: It would be the gentle, herbivorous, ten-ton Steller’s sea cow, because to make it possible we would also have to protect the great kelp forests for them to survive – one of the most dynamic ecosystems on the planet, home of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, sea otters, provisioning seabirds and humans. So, a healthy population of Steller’s sea cows would be the tell-tale mark of a healthy sea.

BB: Which of the many life-affirming, heartbreaking examples of human-animal companionship you write about most touched you?

KC: The Croatian janitor and the wounded stork who couldn’t fly is a very touching and life-affirming story: that he built her a nest around his chimney, that he worried for her stork loneliness, that, after ten years, a male stork landed on the nest to join her and returned every year. Over nearly 20 years, they reared 66 chicks between them!

BB: There’s a lyrical description of you as a 12-year-old galloping on your pony. Also of ‘speechless’ Billy overheard confiding to a horse on Michael Morpurgo’s farm. How can children who grow up without seeing animals – apart from in zoos or on their plates – make that connection?

KC: Maybe we need to turn the question around to ‘how we can make room in our world for all of us to be more connected to our animal cousins everywhere?’. Where we welcome the wild into our cities and parks and gardens. In Berlin, they do this and are rewarded with nightingales. Our disconnect and creature-blindness allows us to destroy animal homes without even realising it. The contagious Tidy Disease clears away the glory and profusion of life. Spraying and eradicating them. There is fathomless beauty and fascination in a ladybird or dragonfly. Peregrines can be found in our cities. We just need to flick the switch.

BB: What eco action would you take if you had a billionaire philanthropist funding you?

KC: Broadly, buy as much unproductive land as possible to restore its ecological health. However, there is a project I’d love to see happen: the first elephant sanctuary in Europe – for rescued elephants from circuses and zoos. A place where they could live out their lives naturally and socialise. Well, a thousand acres with a large dam has now been bought in Portugal. The Pangea Trust just needs to raise enough finance to make it a reality. How somersaultingly lovely to enable that. And, into the bargain, what ecosystem repair! What ecotourism opportunity! Imagine!

BB: Are you vegetarian? Is there such a thing as humane animal farming for human food?

KG: I’m not a vegetarian. I write about this in Beastly. I eat meat sometimes. Nothing of unknown life and death. We are lucky to be able to source (and afford) wild venison, beef from a friend’s farm allowing cows a good life, and free-range eggs from running-around garden chickens. That’s where we are at. I’m sure I am full of hypocrisies. The ecological case for grazing and nutrient-cycling fauna to restore soil fertility gives us our apology – for now. It is expensive, but much cheaper because we eat so little of it – once a week max. However, the numbers tell us nine billion humans will need to move to a plant-based diet, or screw the planet. The bottom line for me is that farm animals must have a life worth living. That means socialising, playing, being outside, being a cow, or a sheep, or a pig wallowing. We can do it properly, and we should. Removing cruelty from food production shouldn’t be a luxury. It should be law.

BB: Your hero and villain in the history of scientific discovery?

KC: The villain is American psychologist Harry Harlow – no contest. I think it’s important to know about people like him; his evil imagination was off the scale. The heroes in Beastly, thank goodness, are many. They carry the story out of the darker places that we need to know about. Like the ethologists who took the study of animal behaviour out of the lab to observe animals in their natural surroundings. One of my favourite moments is when the zoologist, Konrad Lorenz, watches a fish make a decision. It’s incredible.

BB: There’s a huge volume of information in the book. Did you ever feel overwhelmed and how long did it take to write?

KC: A lifetime! Of watching animals, of being human, then about five years of research and writing. I read a shedload of books and scientific papers and interviewed many people. My ambition was to reach out of the nature echo chamber, to engage readers across the board. And yes, I did feel overwhelmed, many, many times. How on earth could I wrangle it together?

BB: Which story would you retrieve from the cutting-room floor?

KC: Well, there was the fascinating revelation of how circus fleas were trained – very popular in Victorian London. Only human fleas are strong and lively enough, apparently. The task is to teach them to walk instead of hop – you can’t have a chariot drawn by a hopping flea. So, you harness them with a noose of fine glass-silk, which fits in a tiny groove between their head and thorax. A tethered flea unable to get anywhere will stop hopping after about two weeks! Feeding time is a simple, but itchy affair. Two hours, morning and night, the trainer presents his hand to his temporarily unharnessed entourage who hungrily suck away.

BB: Many chapters begin with an excerpt from a poem. Which is closest to your heart?

KC: Nina Cassian’s lines, ‘I consumed his heart, and then / on his antlers hung my raincoat’ are very powerful, but there is one poem I quote in full: David Harsent’s ‘Bowland Beth’ which I cannot read aloud without my voice breaking.

BB: You’re passionate about waking us to the remarkable nature of animals we take for granted. If you were a biologist, which creature would you study right now?

KC: Well, thank you! It would have to be the animal more extraordinary than any alien could possibly be. What alien could change shape and colour, regenerate legs that can think for themselves, mimic the surroundings, fake seaweed, grow horns, pop up warts, glow in the dark, pour themselves down a plug, play, dance, squirt you with ink, take off by jet propulsion and taste you all over with their embrace? Guess.

BB: Your description of early attempts to categorise the world’s creatures, especially Linnaeus, is fascinating. Do you have a system for categorising your own bookshelves?

KC: I wish!

BB: Which writers on those shelves inspire you?

KC: I was surprised how much I liked Robin Wall Kimmerer; I thought Braiding Sweetgrass might be too touchy-feely for me, but she is a smart, clear-headed scientist with real sensitivity, and it is a beautiful book. Tim Flannery is brilliant, Frans de Waal is fascinating; Helen Scales is an excellent writer and scientist, both. David Quammen, Tim Birkhead, it goes on…

BB: You mention that Miriam Rothschild would be your dream dinner companion in heaven. Who else would you invite?

KC: Arjan ‘Billy’ Singh the irascible hunter turned conservationist who devoted his life to saving the big cats of India. He would be on one side, Miriam on the other, and opposite would be Simona Kossak and Grey Owl. What a party!

BB: Your next book?

KC: Hmm… I do have an idea, and I wish it would go away!

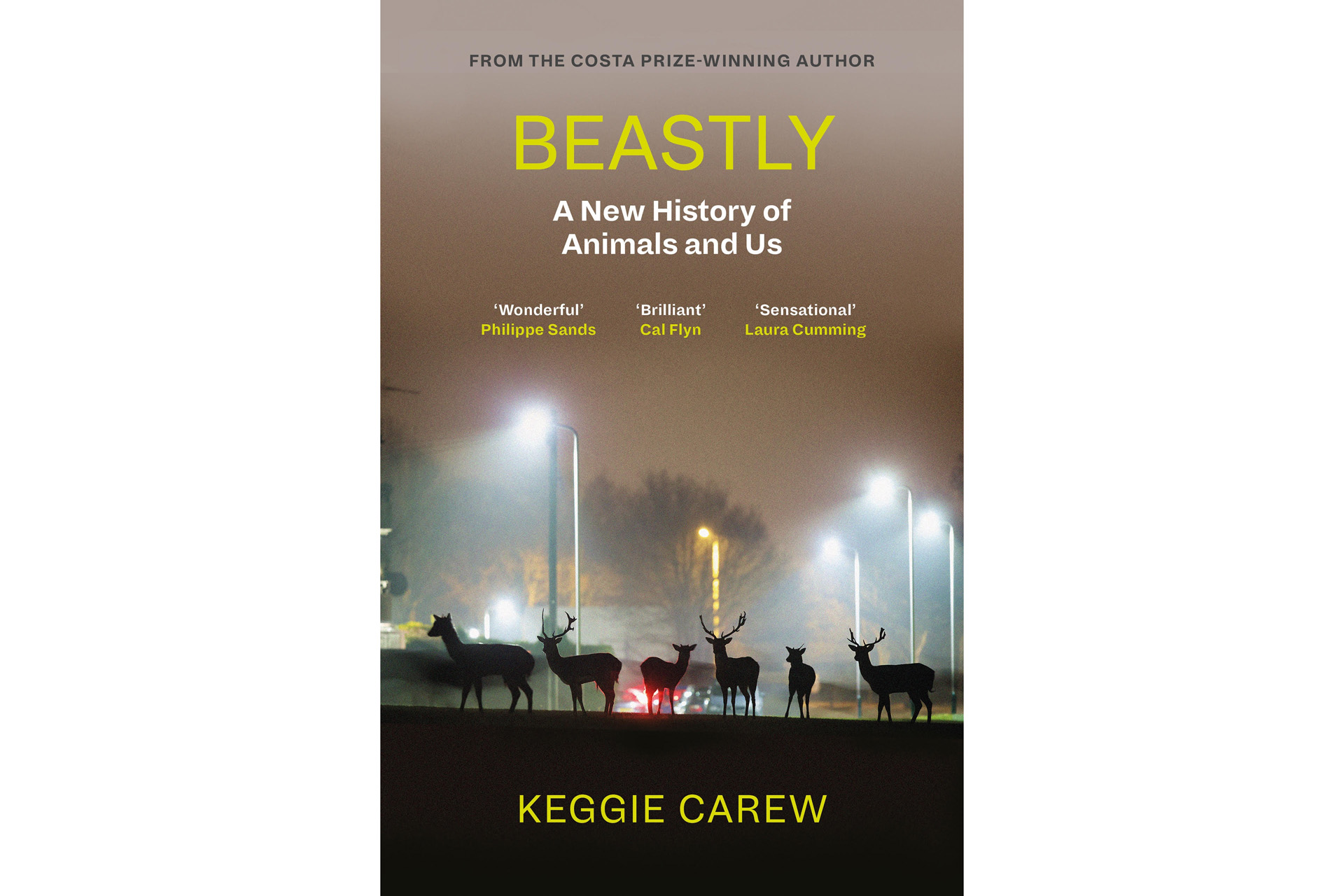

Beastly by Keggie Carew is published by Canongate Books. £15.99, waterstones.com