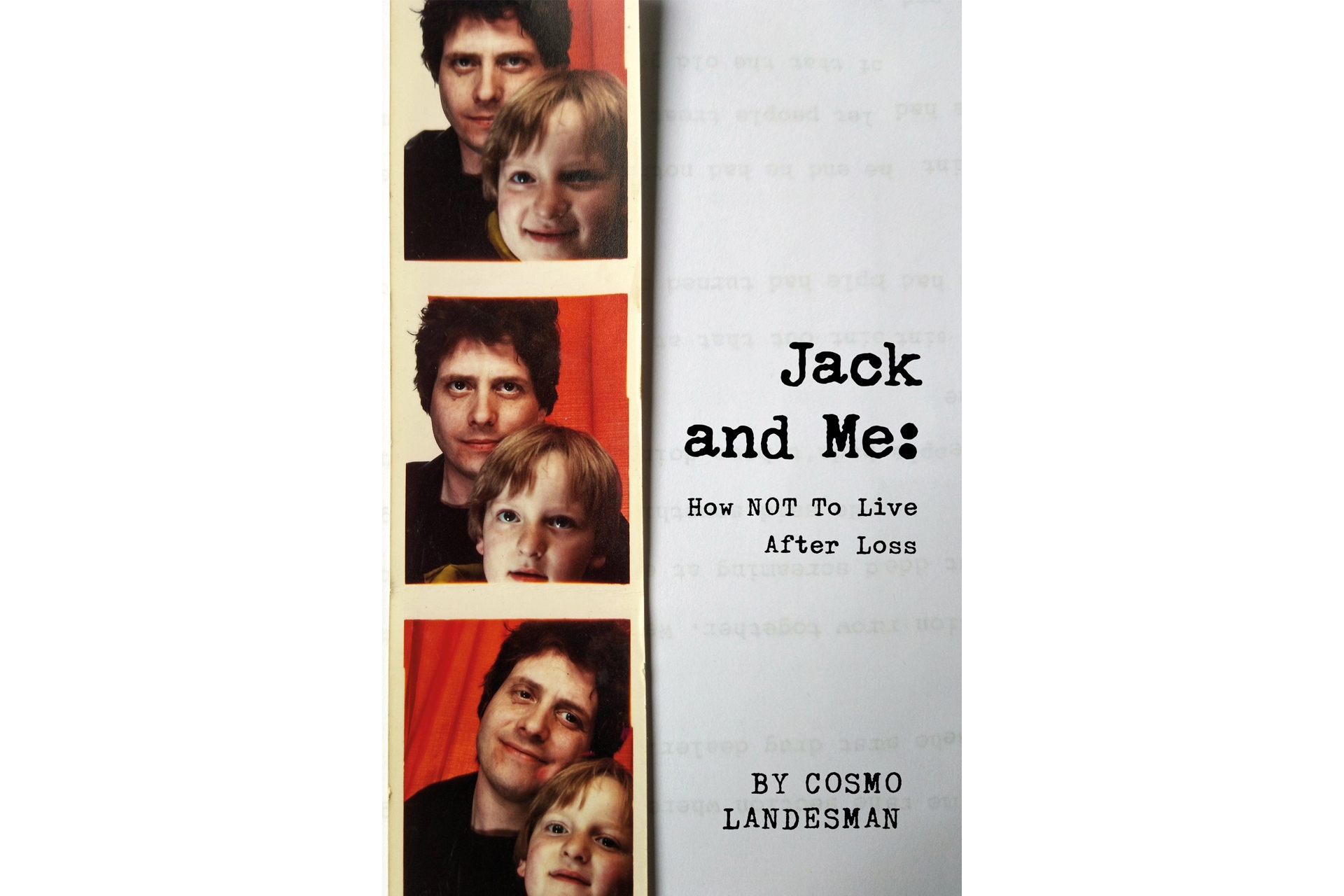

C&TH Book Club: Jack and Me by Cosmo Landesman

By

2 years ago

A sensitive and insightful conversation on guilt and grief

In October’s C&TH Book Club, Cosmo Landesman talks to Belinda Bamber about the anguish of losing a child to suicide, as he launches his memoir Jack and Me: How Not To Live After Loss.

Interview With Cosmo Landesman, Author Of Jack and Me – C&TH Book Club

Belinda Bamber: This is a father-son story in which you try to get to the heart of why Jack took his own life in 2015. As the narrative moves back and forth over his 29 years on earth, you’re unsparing in analysis of your own shortcomings as well as his struggles with drugs and depression. How do you feel as your story hits the bookstores this week?

Cosmo Landesman: I feel a mix of relief and trepidation. Relief because for a long time it looked like the book would never find a publisher. Trepidation because you never know whether it will find readers.

BB: You write beautifully about Jack’s sweetness, as well as your frustration at being unable to change his nihilism. Did writing the book feel like a process of forgiving him, or yourself?

CL: I think I’ve managed to forgive him a lot more than I have forgiven myself. But I’m getting better at the whole business of forgiving. I realise that I was never the great dad I had wanted to be – and I was never the bad dad I always thought I was.

BB: Sometimes I found your self-criticism (‘Shit Dad’) maddening as well as saddening, and this ambivalence seemed to mirror your own frustration with Jack. In what ways were you alike?

CL: For a long while after Jack’s death I refused to accept the idea that I could change and make a good life after his loss. I refused to try therapy. I refused to learn something from his tragedy. There was nothing for me to do but suffer – which is exactly what Jack did. In short: we shared a closed mind to life’s possibilities.

BB: Surprisingly, it’s also a funny narrative, and we get the sense Jack would have laughed at your irony and self-deprecation. It sometimes reads like a letter to him – did you have a reader in mind as you wrote?

CL: I’m glad you find bits that are funny. Books like this are not meant to be funny and people feel awkward about admitting that it was funny or that they enjoyed it. But I’m glad they did. I didn’t have a reader in mind – I had lots of different types of readers. People who had experienced loss and people with a difficult troubled young man in their life. And people who just wanted an interesting read. Ideally this book should appeal to people who have no interest in suicide or loss – or thought they didn’t.

BB: The death of a child is everyone’s greatest fear. Impossibly, I wanted you – as protagonist, father, author – to take action and somehow change the outcome. But words can’t bring people back. Did this change how you feel about the process of writing, the power of the writer?

CL: You can’t write yourself out of grief or regret. But you can write in such a way that gives you perspective on these things. We all have – or will have – come to know loss. I felt that by writing this book I did bring him back into my life.

BB: Both you and Jack’s mother, Julie Burchill, have written about him. What would Jack’s book about his parents look like?

CL: Jack’s book would have been short and to the point. He was a good writer but he didn’t like to write because his parents were both writers. He wouldn’t have said a bad word about his mum – he never did. About me he would have had some harsh words and some kind words. His overall message would be, “Dad, don’t beat yourself up!”

BB: You write about ‘old Jack’ and ‘new Jack’, while he also talked of ‘the old me’. As a society do we pay enough attention to the often-traumatic transition of adolescence?

CL: No. But the trauma of that transition is often a good thing – at least in terms of creativity. It produces youth culture, art, fashion and pop music. But it can also produce depression, isolation and psychosis. It’s the grit that produces the pearl.

BB: There’s a lightbulb moment when you realise you were trying to give Jack the childhood, and the father, you had wanted, rather than the ones he needed. Should baby books be rewritten, exhorting all potential parents to have therapy, rather than giving notes on nappy rash?

CL: I always hate it when during a radio interview the person says to the interviewer, ‘that’s a really good question!’ Well, that’s a really good question! One too big and important to answer in a short space. If therapy would help you to be a better person, or meditation or philosophy, then I think you should try it. Parenting is a skill and like any other skill it takes practice.

BB: I liked your imagined conversations with Jack, which convey your shared humour and love. (Sometimes it feels like he’s the parent comforting you.) Do you still hear his voice in your head?

CL: Yes, and he’s taking the piss out of me!

BB: The rawness of your self-doubt (‘did I love him?’) is painful. Yet the regrets of wrong decisions, misunderstandings and lost temper are all too recognisable for parents everywhere. Your honesty is laudable. Are you too hard on yourself?

CL: People have said that I am. It’s a hard balance to get right. If your child dies by suicide you can’t pretend it had nothing to do with you – at the same time you have to resist thinking it’s all your fault. Blame is too blunt a word to use. Our children can fuck-up their own lives without our help, thanks very much.

BB: Jack was convinced his brain was ‘broken’, and that this made him incapable of navigating life. In these times of unprecedented mental illness among children and young adults, should our health system do more?

CL: Yes. That said the big problem we don’t really talk about is that we don’t know what to do! We have certain preventive measures that can work – unfortunately they don’t work on every potential suicide.

BB: You make a point about the problematic romanticisation of suicide, aided by online forums.

CL: It’s not about online forums – this romanticisation of suicide has a long history in literature and poetry. The cult of Thomas Chatterton and Sylvia Plath were both pre- internet. The real problem is not the romanticisation of suicide but the normalisation of suicide. Suicide has lost its strangeness; its power to instil fear. Now, it’s just another option when faced by suffering.

BB: Should drugs be banned or legalised?

CL: These are both bad options. We boomers who grew up taking drugs failed to understand how bad smoking weed can be on certain young minds. I hear from parents all the time about what smoking weed has done to their teenage son or daughter. It’s a mistake to think that weed – and other drugs – are harmless.

BB: You were still learning how to be a father when Jack was in his 20s, and, touchingly, are still learning now he’s gone. (All parents can and should benefit from this insight, that the learning never stops…) What was the greatest lesson for you?

CL: Be the parent they need, not the parent you wish you had.

BB: Do other fathers relate to your yearning to be super-Dad?

CL: I know that a lot of young dads feel they are failures when it comes to being the kind of father they wanted to be. The funny thing is that they compare themselves to their own dads – who weren’t great dads – and yet still feel inadequate.

BB: One of the many ‘unsayables’ you write about grief is the compelling urge to have sex after Jack died. Were you aiming to shock?

CL: I can honestly say that I never aim to shock; I aim to tell the truth of my experience. I had a lot of doubts about that section but it’s important to challenge our notion of what grief is and how it affects people.

BB: Have you changed your mind about the value of self-help books?

CL: No, I have always thought that self-help books can be of use. I’m an American and we don’t sneer at self-improvement the way you snooty Europeans do! Or the way you used to!

BB: How does it feel when parents of suicidal children ask your advice?

CL: I used to think – why ask me, I couldn’t save my child. How could I help yours? But now I realise that most parents just need to talk to someone who has been there, and I don’t have to save anyone.

BB: Forgive me, but at the end I couldn’t help wondering if you really have turned a corner, or if the publisher asked you to give readers hope? (In the same way that Jack sometimes said what you wanted to hear…)

CL: My publisher didn’t ask me to do anything but finish it! I have definitely made a change in the way I think and act. Of course I still have a lot of work to do.

Jack and Me: How Not To Live After Loss by Cosmo Landesman (Black Spring, £20). bookshop.org