Jen Hadfield On Writing Shetland

By

9 months ago

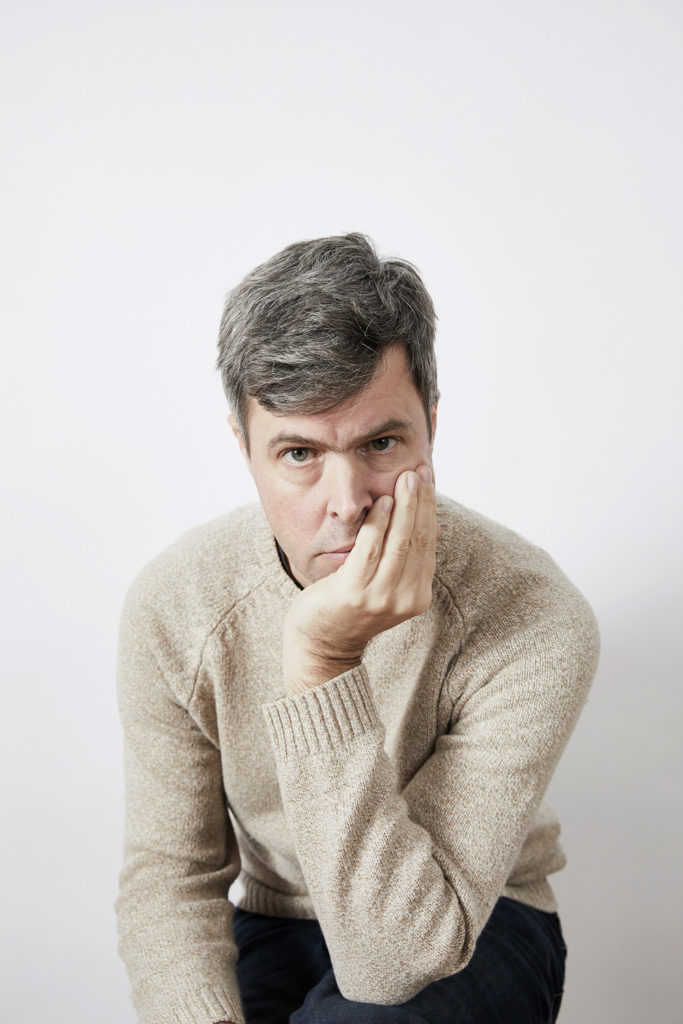

The famed poet on living in and writing about Shetland

In July’s Book Club award-winning poet Jen Hadfield talks to Belinda Bamber about how living in Shetland inspires her work.

C&TH Book Club: Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield

Belinda Bamber: You were brought up in Cheshire, how did your move to Shetland come about?

Jen Hadfield: My mum is Canadian and I think we grew up with this idea of big, open landscapes being a sort of spiritual home, a counter to South Manchester’s suburb-scape. I used to look at towering cumulonimbi from the school bus, or from my attic window, and imagine summits in the sky. When I first visited Shetland in my 20s I felt myself relax in the wide, open landscapes, and I didn’t want to leave. I spent the next few years trying to get back, and when I did – after 15 months living in Canada – I decided to stay. Shetland felt right to me in some way; and I felt welcomed. I still don’t feel I’ve seen all there is to see here.

BB: This issue of Country & Town House is themed on sustainability: regeneration, soil, nature. What does ‘regeneration’ mean to you?

Jen Hadfield: Regeneration is proving a hard word for me to engage with, which is odd, given how important it is to me to leave as light a trace as I can in the wild world. Here in Shetland, words like ‘sustainability’ seem to be used more and more often to greenwash industrial developments, and perhaps the tone of ‘regeneration’ feels similar. A friend who used to work in planning once told me Shetland had always prioritised ‘development over stagnation’, sometimes at the cost of natural landscapes and traditional ways of life (salmon farming might be a key example). But then many traditional industries and crafts here – sheep crofting, Fair Isle knitting, fishing – have been exploitative in some way. Sheep crofting is often at the expense of natural biodiversity, and, at the time of the Clearances, folk were cleared from their homes to make way for more lucrative sheep. Historically, Fair Isle knitters were exploited by what was known as the ‘truck’ system, where knitters were tied into producing high end goods for the fashion market in exchange for credit at the local store. And at the time of the haaf (deep sea) fishing, crofters were induced by the lairds to go to sea in open sixareens, and their catch controlled by the lairds. So we can’t get too romantic about the word ‘traditional’ either.

Shetland is full of talented craftspeople, artists and musicians, and deeply knowledgeable crofters and fishermen. When I first moved here, I was romanced by this intensely creative community which valued homegrown skills and worldly curiosity. Now, as funding is cut across all sectors, and our landscape seems about to be even further dramatically altered by the numerous wind farm proposals taking advantage of the chance to export energy out of Shetland, the Shetland I have known for the past seventeen years seems at a teetering point. Many friends who work in the creative industries here have lost their jobs; our book festival our and world-class film festival, curated by Mark Kermode, have been cancelled; one of our two public galleries has closed.

BB: What gives you hope?

JH: Shetland is far from the only local authority to suffer in this way in these uncertain times, of course, and in fact, thanks to oil money, has fared better than many so far. The other week, a pop-up gallery selling donated local art and craft raised thousands for Palestine. A group of writers have inaugurated a monthly cabaret event showcasing new Shetland writing, film and music, which packed out its wee venue, The Bop Shop. Shetland, over many years, has raised £3.5m for a life-saving MRI scanner. Island communities are resilient, generous, self-reliant and resourceful, and that gives me hope; but no one has much power against energy companies.

BB: What’s the significance of the title, Storm Pegs?

JH: Storm pegs are the extra-strong clothes pegs that can withstand Shetland gales and they mean something to me about embracing weather, I guess. I love to see my laundry on the line here; when I have to be indoors, working, I feel better knowing at least some part of me is outside in the changing air. I use weather as a metaphor for energy and change, too: it is about experiencing and embracing uncertainty as well as the perpetual drama of the volatile sea and skyscapes here. And I like the fact we don’t need a tumble dryer.

BB: You write lyrically of facing up to your fears in Shetland – of heights, of the sea. Does the process of writing make you afraid?

JH: Writing IS frightening, for some reason, and I don’t find my ceramic or visual art practices as intimidating. I think writing can be both easy and gruelling. Storm Pegs represents seventeen years of life in Shetland condensed into some 300 pages: daunting, when your work seeks to create a working model of the universe on the page! And, once it’s published, you can’t take it back. What’s more, I write about real people in this real place, and that carries a great deal of responsibility, I think. You have to respect other people’s wishes and privacy, and give them a chance to withdraw from your narrative.

The prescription is to embrace the risk, of course, and to try and write lightly, even if I publish carefully and with concern. I hold a free, shared, silent writing space intermittently on zoom for other writers too (at https://www.ticketsource.co.uk/jen-hadfield-rogue-seeds): folk seem to find the solidarity of other writers reassuring. I definitely do.

BB: When did you first realise writing was your vocation, and how did you manage to support yourself financially?

JH: I’ve been writing seriously since graduating my MLitt in Creative Writing at Glasgow and Strathclyde Universities in 2002. When I won the T S Eliot Poetry Prize in 2008 I was able to leave my day job and support myself tutoring other writers and performing my own work. It’s been a patchwork kind of income, but the freedom and variety of jobs has been wonderful: translating Kurdish and Iraqi writers in Erbil, teaching MLitt students myself at Glasgow University, introducing primary bairns to poetry at Arvon Writing Centres and working with care-experienced young folk here in Shetland and in the Highlands.

BB: Your book hums with the poetic phrases of the old Shetland language. Do you have a favourite word?

JH: I have a rule now only to use in my writing Shaetlan words that I might use in speech without noticing, or words that I have just encountered for the first time, in order to explore and celebrate them. Shaetlan is a beloved, endangered language and I’m committed to introducing readers to it whenever I can. Shetland has a strong literary history of its own, though, with at least five dictionaries of its own, and a canon of well-loved writers in both Shaetlan and English. I’ve always been particularly moved by Haldane Burgess’s Jubilee Ode, in answer to Tennyson’s poem of the same name which is a paean to Queen Victoria at her Jubilee. Burgess’s poem is a satire, in the Shetland language, which addresses Victoria as a wayward daughter, upbraiding her for neglecting her poorest subjects. It’s a fantastic poem and you can listen to a great recording of it on Shetland ForWirds website here.

BB: After a decade or so living on Shetland, scything grass and living in a caravan while your home was built, do you feel equipped to survive in the wild?

No, not at all! But I do cherish those aspects of self-sufficiency we’re able to achieve: we built a Polycrub last year, which is like a polytunnel engineered to withstand the Shetland weather (designed here in Shetland and reusing old salmon farm pipes in its skeleton) and we grow aubergines, tomatoes, asparagus, lemongrass and strawberries in there. We grow our own tatties and carrots outside, and friends from the Isle of Foula brought us some beautiful kale seedlings which really thrive: the flower shoots in May are really tasty, and the plants are statuesque and gorgeously ornamental. And sometimes we are lucky enough to receive a gift of fish.

BB: Why did you choose a limpet as your daemon?

JH: I seem to search endlessly for images of security and anchoring. Limpets possess a thing called a home-scar – a gutter in the rock that matches exactly the contour of their shell, which they can lock down onto to prevent themselves drying out and dying, and it protects them from predation too. I love the home-scar as an image for how we can feel essentially entangled with our home; how home can feel like it is a matter of life and death. I love their shells too. I fantasise about recreating the shades and sheens of the nacre in porcelain and ceramic glaze.

BB: I was struck by the contiguity you describe between your writing and your life in the Shetland landscape. The soil and stone of Shetland seem to anchor you, while your writing anchors us, the readers. To what extent can writers change the world?

JH: When we let our writing be overdominated by intention – any intention – we run into trouble, I think. So I’m not sure we can deliberately change the world with our writing. I see my job as a writer being to bear witness, and selfishly, I use writing to anchor me and help me process experience in this whirling carousel of consciousness. Writing is like dreaming in that way, perhaps: it helps us process and file away experience so we can meet each day less encumbered and bewildered. Writing is presentness, at its best: I tried to write Storm Pegs entirely in the present tense, to give the reader the sensation of a parade of rich and dizzying Here-and-Nows, but I did have to use the past tense in the end a bit, to create a more coherent narrative. The stone and the soil ARE very anchoring though. And the sea and sky a reminder that stability is always an illusion.

BB: And… which writers inspire and anchor you?

JH: Annie Dillard, Annie E Proulx, Sharon Olds

BB: You write about the Viking Wind farm controversy from its early days and the different reactions of your neighbours. How are you currently feeling about this as an eco option, given it’s in your own backyard?

JH: As I write there has just been another peatslide at one of the windfarm sites. A few days ago we were sailing up the East coast of Shetland and anchored up in a sheltered bay in South Nesting – it has one of the most beautiful crofts and crofthouses on a spit of land, and is rich in wildlife. The windfarm – one lobe of it – bristles along the entire western horizon there now; we find that wherever we walk or sail in Shetland now we can see one corner of it or another. Its appearance is not the only reason the windfarm is ill-sited; it is out of scale to the landscape, raised on unstable ground in many places, in the midst of vital nesting territories for rare bird species (such as red-throated divers), and perhaps, the most painful thing of all, built largely without the consent of the Shetlanders who live in sight and sound of these massive turbines. The excavation of deep peat for the ‘development’ releases, I’m told, massive amounts of carbon dioxide. The energy will power homes on the mainland, not here. It’s hard to come to terms with, even as we try to make the best of a bad deal, and it has made many folk in our community feel powerless, which is grimly ironic.

BB: You’ve won several awards, including recently a £140,000 Windham-Campbell Prize, and in 2009 were the youngest-ever winner of the TS Eliot poetry prize; you’re also a visual artist, university teacher and mother. You write very relatably in Storm Pegs about working through moments of darkness and doubt. How does that balancing act feel right now?

JH: At times, it feels quite difficult: I’m answering these questions at 5am, while the baby, who is teething, sleeps. Writing has more often had to take second place to making a living, so I feel very awed by my luck at being awarded a Windham Campbell prize for my poetry, which will really change our lives immeasurably. It’s a great honour, and I’m hugely grateful, especially since it will mean that I can spend time with our little boy as maternity leave ends. As for creativity and motherhood; it seems most possible to do both when I go with Robin’s rhythms and seize wee opportunities here and there to make something. Planning to write, at the moment, isn’t really a goer. He does like watching me in the garden, though, and we all love our walks.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield is out now. Pan Macmillan, £18.99. bookshop.org