C&TH Book Club: Nonfiction by Julie Myerson

By

3 years ago

'A raw, honest portrayal that’s harrowing to read... yet beautifully written'

In this latest episode of the C&TH Book Club, Julie Myerson talks to Belinda Bamber about writing, motherhood and addiction in her latest novel, Nonfiction.

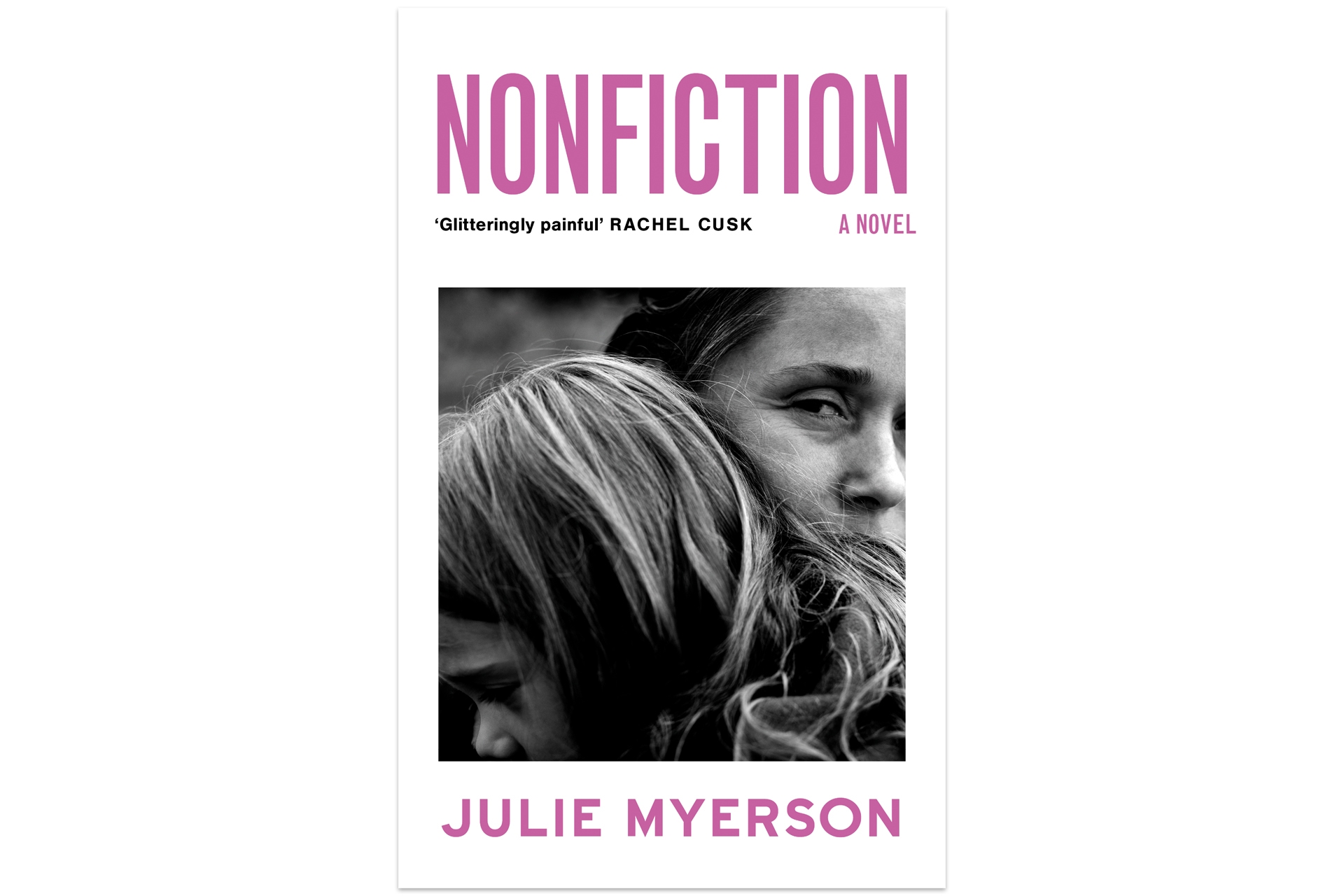

Nonfiction by Julie Myerson

Belinda Bamber: Nonfiction is a novel written from the point of view of a mother addressing her drug-addicted daughter. It’s a raw, honest portrayal that’s harrowing to read at times, yet beautifully written and impossible to put down. Why did you decide to address the daughter as ‘you’ and how did that affect the way you told the story?

Julie Myerson: ‘Decide’ feels like slightly the wrong word – I don’t ever ‘decide’ anything when I’m writing fiction, or not consciously anyway. I’m just feeling around in the dark, trying things out, I’m very instinctive about it. But I do know very quickly if something feels right – by which I mean, if it excites me, takes me slightly out of my comfort zone… This is the feeling I’m looking for and if I get it from whatever I’ve just written, then I go with it. If I don’t, then I delete. The ‘you’ would have come about like that. Perhaps also – and this only came to me just now – something about ‘you’ stopped it feeling like something I was just relating events to the reader (she did this, she did that…) and seemed to give the whole thing a far more personal and intense feeling. So perhaps it was a decision after all!

BB: The protagonist lacerates herself for being ‘a bad mother’, fearing she might be responsible for her adored daughter’s addiction. Being unable to protect one’s child from harm is a particular agony of parenting. With all the love in the world it’s impossible to guarantee their safety. Aren’t we all ultimately ‘bad’ mothers in our well-intentioned way? What would it mean to be a ‘good’ mother?

JM: Hmm, difficult question. I don’t like the words ‘good’ and ‘bad’ very much – and if my narrator uses that word, it’s definitely her talking and not me! I think most mothers are just trying their best to do the right thing for roughly the right reasons. A ‘good enough’ parent, in other words….

But yes, the sense of powerlessness, the inability to protect your child from harm. Almost all of my novels (especially Laura Blundy, Something Might Happen, The Story of You) seem to be addressing this particular agony of parenting in one way or another and yet most of them were written when our kids were young and our family was very unproblematic. Strange, I know…

But in Nonfiction I was definitely trying to evoke the very particular and terrible sense of powerlessness which goes with drug addiction. This is alien to ‘normal’ people and depressingly familiar to anyone who’s dealt with an addict, especially one they love. Someone once told me that a definition of stress is responsibility without power. All families of addicts have been there.

BB: Given the media furore after publication of ‘The Lost Child: A True Story’ about your own son’s addiction, I was surprised to find you re-entering the lion’s den with Nonfiction. You almost taunt critics in this novel, by continually blurring the lines between fiction and autobiography – not least with the title. The gender of the child has changed, but the mother is a novelist. Why did you go back into the zone?

JM: Again, it wasn’t a decision. This book went through so many, many drafts and much of the time I didn’t know quite what it was about – I never do! But I was a bit surprised to discover I still had something I needed to say about addiction and families – and also about writing. The writing part surprised me a bit, but it was deeply satisfying to allow myself to explore it.

I did say to Jake: ‘I’m writing a new novel which isn’t about you but because it’s about addiction, I’m afraid every single review is going to mention The Lost Child’. I knew it wasn’t ideal, in fact I was quite worried. But he was remarkably cool about it – more than that, he was encouraging. I know that he thinks I should get myself back out there. Very generous of him but also very typical.

Photographer: Barney Jones

BB: The narrator’s mother is a bitter, interesting woman, whose backstory reveals a history of fracture. Could that matrilineal legacy have influenced the daughter’s addiction, like a wound passed through flesh and bone. Is she acting out the unspoken pain and grief of earlier, damaged generations who were unable to communicate – or receive – love? Or is that idea too far-fetched?

JM: I don’t think it’s far-fetched at all but it’s hard for me to expand on that – you’ve put it rather well! I don’t know. The part where the relationship between the mother and daughter is, briefly, beautifully normal, is something that really happened. My mother had a small stroke a few years before she died and for about 18 months, she seemed to lose all of her anger and her sense of humour and kindness came back. It was blissful and I was amazed at how happy it made me, almost in a childlike way. I hold onto that still. And the love I felt was instant – I suppose it reminded me how very deeply I did love her. It was very very hard when, almost overnight, she turned back into her old self again. The tragic thing is that both of those ‘selves’ were in a way, her real self. She just lost her anger for a while and that was all it took for the other one to surface. Unfortunately anger really fuelled her last few years and I found this very painful, that it became her legacy when it shouldn’t have.

BB: The part of the story that works less well for me is the narrator’s love affair with her ex-boyfriend, even though it offers a parallel addiction story that’s capable of destroying her life. Perhaps I’m projecting my own need for the narrator’s marriage to be the stable point of a turbulent, upsetting story. Does it surprise or irritate you when readers steal your narratives to fit themselves?

JM: Ha! no it doesn’t irritate me, not at all. I rather love it. Readers of course bring their own stuff to a book and that’s the deal. In fact my personal theory about what constitutes a so-called ‘literary’ novel is exactly that: not only will it seem like a slightly different book to each new reader because of what they personally bring to it, but you can also read it a second or a third time in your life and – because you yourself will have changed and grown – it will feel like a very different piece of work all over again. (This has happened to me with many novels but Wuthering Heights in particular springs to mind). I think it’s something to do with prose that doesn’t try to tell you absolutely everything, that leaves some space for the reader and, in a way, for itself. I find this very exciting. It’s certainly why I read and why I write.

And speaking of the affair… some readers have noticed that – like much else in the novel – it might just be something the narrator’s been writing (there are clues). Perhaps I was too subtle about it, but then again I’m not sure it matters. All I’m trying to say is that it’s impossible to pin down what’s real and what isn’t. For a writer, truth and fact, fiction and lived experience – they all inevitably blend to become a whole new truth. And again, it’s why I write. I think that’s beautiful.

BB: The limits of love are explored in both the parent-child relationships and the marriage in Nonfiction. There’s a hollowness to the characters’ oft-repeated declarations of ‘I love you’, because they invariably accompany actions that hurt. Flawed and broken as we are, are humans capable of giving the unconditional love we long for?

JM: Yes of course we are! We have to believe that, surely? But if what you’re saying is, am I trying to write about love in an unsentimental way, then yes, definitely. Love in all its guises, hopefully not sentimentalised, permeates all my novels. And what is love in a marriage, after all? Sticking with it, caring, being kind, compromising – a shared history. There’s a lot of joy to be had in that. And a sense of humour is also important! Love in parenting is, I’ve come to feel, keeping a hold of your sense of humour, moving on, letting things go. I would hope we’ve tried to do that with all of our children, but my mother didn’t seem able to do it with me. (Though of course I would say that, wouldn’t I…)

BB: You once said you prefer not to have therapy because it could take away your writing material. In Nonfiction the protagonist says: ‘I don’t know who I am without my most unforgiving and self-lacerating thoughts’. You seem fearless in exploring self-doubt through your work. To what extent do you gain self-knowledge through your writing and have any of your books changed your sense of yourself?

JM: Hmm… I might have said that about therapy but I think I might also have changed my mind! I’ve had CFS (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) in a moderate way for the past few years and it has definitely impacted on my health and there is almost certainly a stress/mental health aspect to it. I’m considering some therapy at the moment.

When I write fiction, it doesn’t feel like therapy and I wouldn’t want it to. However, I do think there is something inherently mentally healthy about exploring what’s in your head and trying to express it as truthfully as possible – it’s quite a luxury and I feel lucky to have earned a living doing it. Let’s not forget that it’s also art, with all the artifice that implies. I came across a wonderful quote the other day from a writer called David Shields, who said: ‘I like to write stuff that’s only an inch from life, from what really happened, but all the art of course is in that inch.’ Yes, I thought! That inch. That, more than almost anything else, is what inspired me to write Nonfiction.

BB: The narrator’s father commits suicide in Nonfiction, as yours did. Would you have been a different writer if you’d had a different childhood? Would you have become a writer at all?

JM: I think I was just born like this. Reading Ladybird books when I was about four gave me butterflies in my tummy. And I was nine or ten years old when I sat down and ‘read’ Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (I surely can’t have understood much of it) and something – literally – about the arrangement of the words on the page excited me so deeply. I still remember the feeling of possibility. ‘I can do that!’ I said to myself. No one else in our family was a writer, we didn’t know writers (both my parents left school at 15). But my mother loved reading and she passed that on to me – it was her copy of Shakespeare, after all – so much credit goes to her.

BB: You capture the often-unspoken banality of tragedy in Nonfiction: the continuing mechanics of life in the midst of trauma and even death. Your constant seeking after truth, however unpalatable, is one of the remarkable qualities of your writing. Which authors do you admire for their honesty?

JM: I think what I’m always yearning for is not honesty of fact so much as honesty of expression. Rachel Cusk’s incredible Outline trilogy seems to create a whole new way of ‘telling’ that feels remarkable and fresh for its apparent honesty (though there is SO much art in it!). And more recently Sally Rooney’s work, especially Conversations with Friends. Such an intelligent and apparently open piece of work, it just shimmers with reality. Real people, real talking, real thinking. It’s a universal book because you can read it at my age (62) and instantly remember how it felt to be young.

BB: As a writer you seem to compelled to push the boundaries of what most frightens you in life. Are you placating the Fates, preparing yourself for the worst, or compulsively drawn to the dark side?

JM: Yes, I do write about the things that frighten me, always have, perhaps not to placate the Fates but to, I suppose, prepare myself. It’s like sneaking a peak into an abyss. Perhaps my childhood did do this to me, but – even though my default setting is happy and optimistic – I am nevertheless always readying myself for the worst to happen, always getting to places early, never taking anything for granted, preparing to behave as well as I can. I am always slightly on edge. If the doorbell rings, I sometimes give a little scream (seriously, it drives my family mad). I wish I wasn’t like this. It’s something to do with the sympathetic nervous system I think and you won’t be surprised to hear it’s one of the reasons I’m considering having some therapy!

BB: How does it feel when you finish writing a book? Relief or regret?

JM: People have this idea – fuelled perhaps by writers in films! – that an author writes ‘The End’ and then presses ‘carriage return’ and sits back, satisfied. I wish! In fact when I wrote the last line of Nonfiction, it wasn’t the last line, or I didn’t realise it was, not yet. And then, once I felt I’d got the ending right (which took a while), I went back to the beginning and rewrote it, a whole other draft. There isn’t a line in the book that hasn’t been worked over maybe (I’m guessing) 50 or 60 times. For me the real END came when I sent it to my agent Karolina Sutton and she understood it so perfectly, and wrote me such a wonderful email about it that I printed it out and stuck it on my wall.

BB: Forget the negative of the pram in the hall, what most women need in order to create is the positive of a supportive partner. Who or what would you gift an aspiring writer?

JM: I think to share your life with someone who understands that a person can’t be entirely happy until they’ve at least tried to write the book that seems to be bubbling up inside them – as my husband Jonathan did and does – is quite a gift. But also…. a room with a door that shuts. I began my first novel by writing just ten minutes a day, evenings and weekends. I had an office job , two toddlers and another baby on the way at the time – and, yes, a husband who did a whole lot of childcare. But once I shut that door and dived back into my novel, I was somewhere else entirely. I had no idea that it would necessarily be published but I still remember it as one of the most euphoric experiences of my life.

BB: Have you and your son forgiven each other for writing / talking publicly about his addiction crisis? Looking back, would you change anything?

JM: Yes, of course we have forgiven each other – though on my part there was never anything to forgive. And in fact – and this is very important to me – we never stopped talking to each other, even though the press did their best to imply that. His father and I were constantly in touch with him, desperately trying to help him throughout this time.

Do I feel responsible for what I put him through? Yes. deeply responsible. That shame will always be with me. But do I regret having tried to speak honestly about the health emergency that is skunk cannabis? Not really. I had a massive response from people who’d been through what we’d been through, all of whom said my book had stopped them feeling so alone. So many families are going through this. How can any of us ever understand anything unless we’re willing to share our experiences as honestly as possible?

BB: You contribute to TV and radio programmes less often these days – is that a personal decision?

JM: Well sadly The Review Show came to an end. I’m not sure why. I miss it as much as a viewer as I do as a panellist! It was one of the best and most unexpected experiences of my life doing that show – unexpected in that I was a pretty shy person who never dreamed she’d have dared do regular live TV. And some of the art I saw, read, watched and experienced while doing the show actually changed my life. I did lose my nerve for a bit after The Lost Child – a kind of stage fright – but I feel I’m back out there now, I’ll do anything that’s thrown at me. Also, I had breast cancer last year and a strange and unexpected upside of that is that I feel a little bit stronger and braver about almost everything.

BB: Despite an award-winning career spanning 30 years and 14 books, your work isn’t well stocked, at least not by my local bookshops. Is that a reaction to the furore around The Lost Child or a reflection of the trend towards newer, younger writers?

JM: What awards?! I wish! Something Might Happen was longlisted for the Booker which felt amazing at the time, but none of my books have won anything. I’ve joked about it but I’d be so delighted if I could just be LONGlisted for the Women’s Prize one day! I’m neither award-winning nor best-selling, though when I do events, people often introduce me as both (I’m never sure whether to correct them or not)! More seriously though, it’s pointless to think too much about these things, an unnecessary distraction. Just put your head down and do the best work you can possibly do. I know that I’m a far better writer than I was 30-odd years ago and there’s a lot of satisfaction in that.

BB: Are you working on another book?

JM: Of course!! I can’t talk about it – I never talk about my work in progress to a soul, not even my husband. But it’s going well… I think. I’m excited. I will say this: it’s entirely different from anything else I’ve written and yet I could never have written it if I hadn’t written Nonfiction. Each of my novels seems to follow on from the last one in a way that remains mysterious even to me.

Nonfiction by Julie Myerson, £16.98. bookshop.org

READ MORE

C&TH Book Club: Homesick by Jennifer Croft / C&TH Book Club: Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus