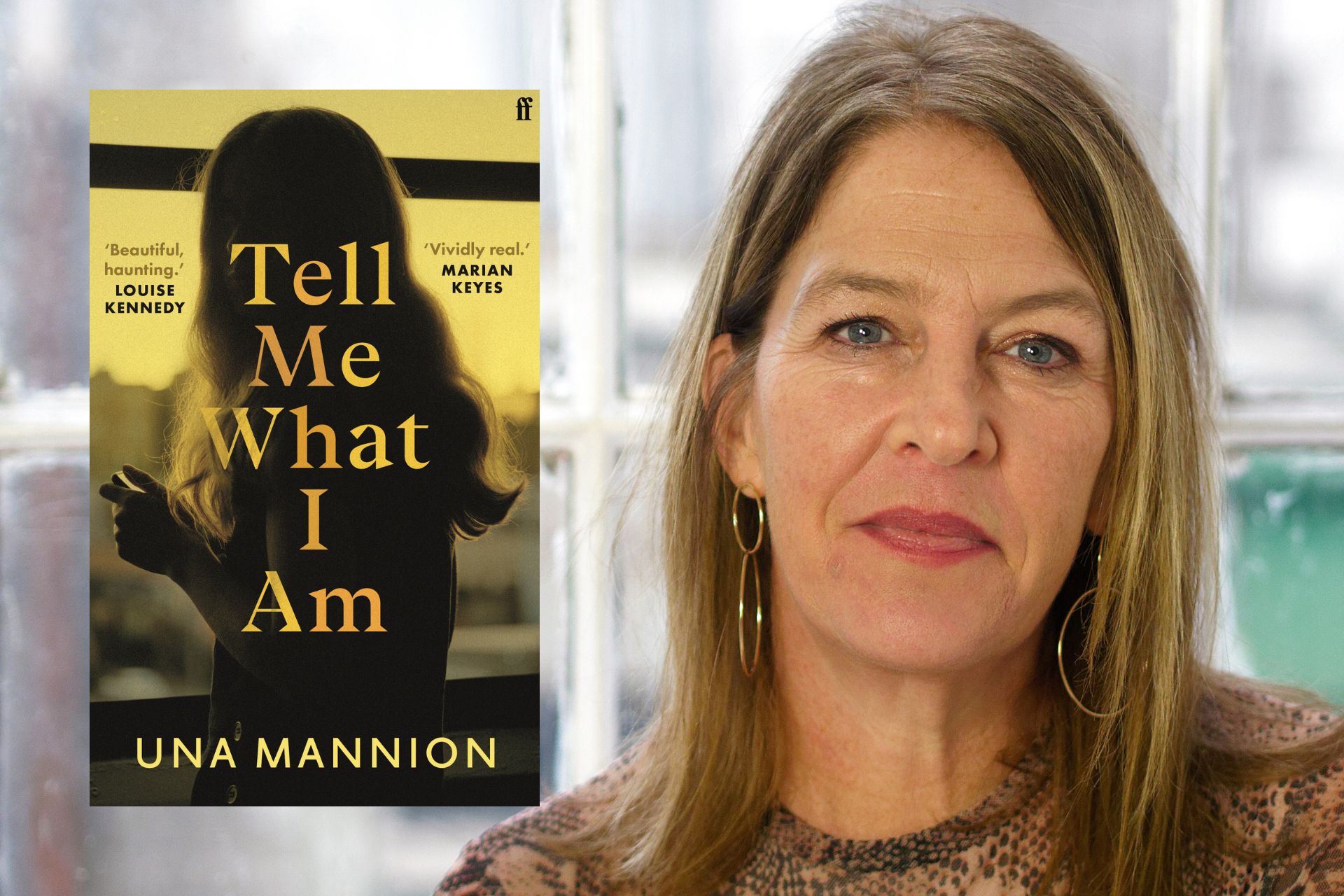

C&TH Book Club: Tell Me What I Am By Una Mannion

By

2 years ago

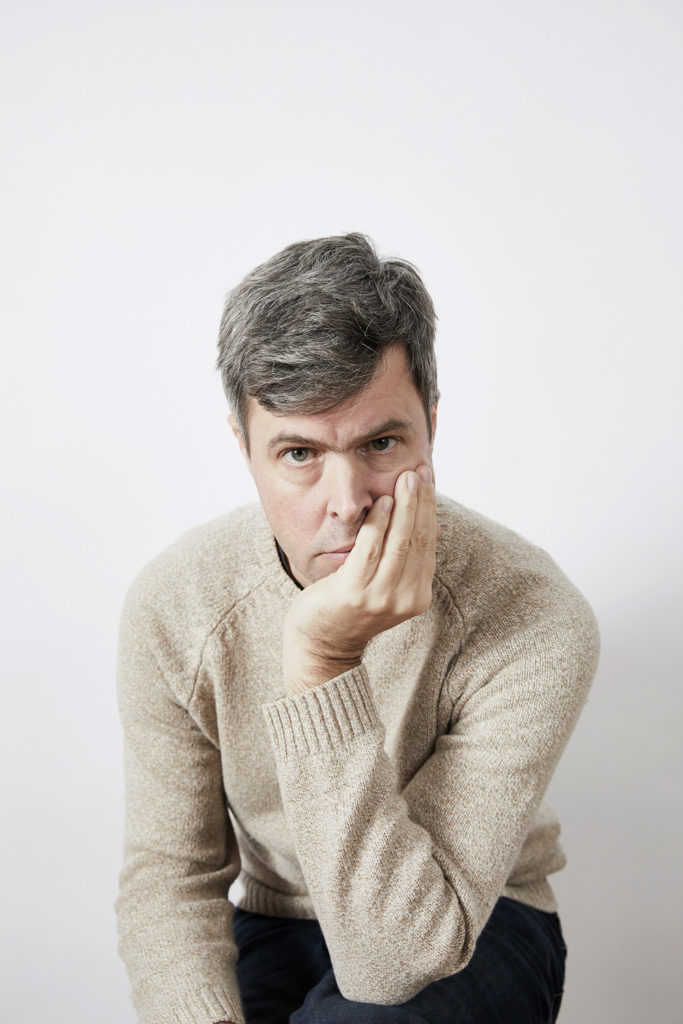

Belinda Bamber chats to Una Mannion

In June’s Book Club, Una Mannion tells Belinda Bamber that true crime stories about missing women and mothers inspired her new novel.

C&TH Book Club: Tell Me What I Am by Una Mannion

© Róisín Loughrey

Belinda Bamber: Tell Me What I Am is the gripping story of a young girl, Ruby, and her quest for her missing past, including the identity of the mother who – she’s been told – abandoned her as a baby. Her growing suspicions about her father are fuelled by her long-lost Aunt Nessa’s attempts to make contact. What inspired it?

Una Mannion: I had started reading about missing persons. In many of the cases of missing women and mothers, an estranged partner who has gained full custody of the children is mentioned as a person of interest in the disappearance. It made me wonder who helps those children remember their mothers if they are cut off from the mother’s family. That erasure seemed the cruellest part of the disappearance, taking away the memory. I teach Antigone every year and we read Latin American adaptations where the mythical story is used to talk about the disappeared. While those adaptations focus on the politically-disappeared, they seem to get to the crux of the cultural anxiety the missing person creates, the lack of closure, the need to make their absence present in the consciousness. While I have written a crime novel in certain respects – a mother leaves for work one day and never arrives – it is also a book about memory, how we remember and how we forget.

BB: The narrative covers 14 years, in which Ruby’s life in rural Vermont gradually intersects with Nessa’s, 400 miles away in Pennsylvania, as each seeks the truth about what happened to Deena. You interweave their stories with that of Deena’s before she went missing. How did you go about mapping this intricately woven plot?

UM: The interweaving or braiding of the two narratives took time and engineering. Ruby’s narrative is largely chronological while Nessa’s plot moves forwards and backwards, and loops around Ruby’s coming of age story. I guess I wanted to show how the past persists, even though Ruby’s father has tried to erase it. I was trying to show parallels between the mother and daughter, moments where their experiences intersect even though the events are 20 years apart. I wrote the two narratives separately. First Ruby’s and then Nessa’s. In the third draft I started to tweak so that the stories were consistent and then I started to stagger the scenes, a few from Ruby and then a few from Nessa. My youngest daughter came up with the suggestion of using coloured post-its with chapter descriptions as a way to start visually diagramming the plot on a wall. It was so helpful to see it and to be able to move post-its around, considering the implications of juxtaposing certain of Nessa’s scenes next to salient moments in Ruby’s story. It went through several iterations before I felt it was working.

BB: Lucas is a strongly realised portrait of a man who sees himself as a devoted father, yet whose need for control is sometimes chilling. How did this character come to you and did your sense of him change in any way as you were writing?

UM: Part of the challenge of writing Lucas’ character was to resist the impulse to completely vilify him as a controlling partner and father. It was important to calibrate the menacing, controlling aspects of his character with traits that make him compelling, that explain why someone like Deena is so immediately drawn to him and how he is able to diminish her ability to make her own decisions. The danger of men like Lucas is that they are often charismatic. When I was first writing Lucas it was from Nessa’s perspective and her representation of him is quite one-dimensional. Her radar is up from the first time she meets him. She doesn’t like him, she sees all the power-tells in his physical behaviour, and she sees her sister disappearing in the relationship, long before she actually vanishes.

Writing Lucas from his daughter Ruby’s perspective helped flesh him out more and, I hope, made him more nuanced. Initially, I avoided writing about Lucas. I had to add scenes to develop their relationship, the tenderness and understanding as well as the undercurrent of control and threat. That was hard because I didn’t want to give him those scenes or give him any credit for the powerful person Ruby is. Scenes I added included the chicks arriving by post and the scene where they go turkey hunting, moments where Ruby thinks he is everything and where they have an understanding that is instinctive.

Because of this, I began to wonder about Lucas’ childhood and what possible damage made him become this person. It’s not that I found empathy for him but I think I made a genuine effort to show the desperation and emptiness at the source of his pathology and that I continued to think of him as a character rather than a caricature or parody of a controlling abuser.

BB: Ruby, Nessa and Deena make for a memorable trio of women, each very different. I was struck that Deena, as the most feminine and flirtatious of the three, is also the most vulnerable, while Ruby and Nessa are more wary, more resilient. It’s notable that, as a keen rower, Ruby becomes physically muscular and strong as a teenager. Do you think there’s a connection between physical and emotional strength for women?

UM: Wow. This observation has stopped me in my tracks. I hope I haven’t penalised women for being more feminine or flirtatious or suggest that this makes them more likely to be less resilient or potentially victimised. That definitely was not my intention. But I guess at an unconscious level there is a suggestion that physical strength and psychological armour help make us more resilient.

Nessa is wary but perhaps to the point that she can’t move on or develop intimate relationships. Ruby’s physical strength was a conscious choice. I wanted her to be a teenager whose social currency is connected to her intelligence, empathy and physical strength. That physical strength also becomes an exit route for her and gives her agency and independence. So in her case physical and emotional strength are connected but this is certainly not the case for all women.

BB: Ruby’s grandmother, Clover, helps to raise her. It’s a fascinating portrayal of a woman caught between loyalty to her son, Lucas, and to her granddaughter. She’s the fourth key female character in the story, who knows much more than she tells. She’s not likeable, yet you describe her with a clear-eyed compassion. Where did she come from?

UM: I had read countless stories of missing women where the partner’s mother was the key alibi in protecting them. Then I started reading accounts where a conviction was obtained when a mother changed her story, remembered something or didn’t want to die with something on her conscience. I don’t want to give a spoiler but those stories inspired the character of Clover. When Deena first meets her, she meets a woman who seems defeated, cowed by her son and perhaps worn down by other men in her life. Her relationship with her granddaughter and a friendship with her neighbour Adelaide awakens something in her. Yes, she tries to protect Lucas. She is a mother. But through other relationships and the strength of those women, she begins to stand up for herself and she instinctively starts to protect Ruby.

BB: There are echoes of The Tempest and I loved Ruby’s biting critique of Prospero. A quote from that play in the preface shows where you got the title: Tell Me What I Am. Did you have that in mind when you started writing?

UM: Yes. The book echoes The Tempest. A father takes a daughter to an isolated island space and then controls her story, laying down memories for her, telling her who she is. For a long time I knew I wanted to write about a mother who disappears, where her estranged partner is the suspect. I wondered who helps the child remember the mother if the father has full custody. Prospero and Miranda came to mind. Prospero is obsessed with the story of the past. He constantly tells others to shut up and he will tell them their story. He controls history both in terms of his family and also the colonial history of the island through Ariel’s and Caliban’s stories.

Shakespeare’s text is in many ways about memory, how we remember and how we forget, the violence of forced forgetting. I’ve been teaching Shakespeare for about 15 years. The trope of absent mothers has always interested me and, alongside that, Shakespeare seems interested in controlling fathers. I love when students call out the relationship between Prospero and Miranda. ‘Wait. What? He just knocks his daughter out with drugs or spells when it’s not convenient to have her awake?’

BB: The sisterly bond between Nessa and Deena is touching – does that reflect your own experience of family?

UM: I have five sisters and two brothers. Sibling relationships seem to surface in everything I write. I know that when I was young I could not separate my experiences from my siblings’. I felt their pain and their happiness like it was my own. One of the heartbreaks of growing up is losing that sense of being inextricably connected, not knowing where they end and you begin. Even though we are separated geographically and in our interests and lifestyles, it is still my sisters that will be there when I am in deep need. The bond between Nessa and Deena is often fraught but persists despite Lucas’ effort to dissolve it.

BB: What aspects of writing the novel did you most enjoy and how long was the gestation?

UM: I love researching. I loved looking at the Champlain islands, reading about the history, looking up plants and species particular to that region. I had the opportunity to talk to people who’ve lived there all their lives, hunting and fishing. I had kayaked around the lake and had rambled around some of the small islands. I also spent several days in Philadelphia with a former homicide detective. Through him I had the opportunity to go to the criminal court and watch cases but also spent a day in the Round House where the homicide unit is based. I spent time on Google Maps walking down streets and looking at bridges and trees. Getting the plot down can be challenging but the research helps because it is the little details you trip across that start to give the story authenticity and vigour.

BB: Do you have a regular writing routine and place to work?

UM: In terms of routine, I would like to be more consistent. I tend to write for intense bursts, all day every day for several weeks. I also need a consistent space. I used to have a caravan parked outside my door that I worked in. Now I rent a space. In my new house I hope to have a garden shed that I can convert into a space where I can work.

BB: You were born in Philadelphia and now live in County Sligo, Ireland. The sisters in the novel also have an Irish background. Can you tell us more about your Irish connection and what it means to you?

UM: Even though I have lived most of my life in Ireland, I have yet to set a novel here. A part of me still worries that people will wonder ‘who does she think she is writing about us?’ When I do set stories in Ireland it’s often from that position of a hyphenated identity, here but not from here. My father emigrated from County Sligo in 1953. He met my mother in Philadelphia in the late 1950s and they had eight children in ten years. And then divorced. It was very unusual at the time and for years, over a decade, we were not allowed to tell his family in Ireland. His parents never knew. He kept coming home to Ireland and brought some of us with him each time. I came first when I was six and then spent the summers when I was 12 and 13.

Perhaps more than other Irish Americans who were first generation, my siblings and I had inherited my father’s sense of being caught between two places. He never quite settled in America, never owned property or lived in one place, but still didn’t quite belong back at home. I guess this instilled a loss in me that I carry. In the novel Nessa’s father brings Irish over every year to work on his contracting business. She resists this, ignores the Irish, forgets them and their names. Yet, the first meaningful relationship she has is with one of them. Despite trying to reject the immigrant connections her father can’t let go of, it is ultimately what draws her, where she feels most at home with another person.

BB: I like the title, The Cormorant, of the broadsheet of prose and poetry you edit. It suggests you’re someone who loves the wild coast. How and why did you start it up?

UM: Thank you for saying that. It seems like cormorants keep sentinel here along the Sligo coast. They overlook the estuaries from the rocks and line the high walls of the harbour in town. They are synonymous with the northwest coastline and do seem to keep watch. Legend says they carried messages between the living and the dead. The title of the broadsheet was also inspired by a poem written by the late Dermot Healy who was based here in the northwest of Ireland and had been an editor of a journal called FORCE 10 which had a particular editorial ethos of publishing very well-known writers like Seamus Heaney alongside writers being published for the very first time or beside spoken word interviews with local characters. We wanted a publication with a similar democracy and we wanted it to be tactile. A thing you could hold rather than read on a screen. The idea of a broadsheet came out of this. We’ve just published our eighth edition.

BB: You’ve won prizes for both poetry and prose – does one come more naturally than the other? And at what point in your life did you know you were a writer?

UM: I am not sure that either feels like it comes naturally, but prose comes with less difficulty. I love poetry and often read verse before I start a day of writing to get me into words, into a way of seeing or something. I still find it hard to say I am a writer. I am trying to write and I am trying to write with integrity, about things that I care about and I have been trying to do this consistently for about ten years.

I knew I wanted to write when I was in my twenties but didn’t start writing until my late forties. I wish I could tell my younger self what it feels like to finish a piece of writing, to have crafted it to a point where you know that there is not much more in your capacity to do to make it better, that sense of accomplishment. It has nothing to do with getting it published or read by anyone else. Just between you and yourself, having created something and put it into the world.

BB: Tell Me What I Am is hard to put down. Is it possible to learn how to write a page-turner? Did you attend any classes or workshops when you were learning your craft, and what advice do you give aspiring writers?

UM: I think the best way to learn how to write is to read and read and read. And write and write and write. After a stint with a writing group where I had started to write stories, I applied for an MA in writing and this was beyond formative in so many ways. I was pushed to start a long form work (my first novel), and, more importantly, I had given myself permission to write. But we didn’t talk about writing a thriller or a page-turner or discuss pace. I think instinctively I am clutching on to the reader, imploring them to stay with me. Don’t go. I think that I am writing literary fiction because I am deeply interested in language and character. But I am also drawn to true crime and mystery. There is something about a literary crime that is incredibly compelling: the real drama of the mysterious or random experience of existence but also the language and metaphor trying to make sense of it.

BB: Which authors do you reach for when you need re-centring, in both life and writing?

UM: I think I reach for writers who reassure me about connection to humanity and to the natural world. This solace comes from both fiction and nonfiction, poetry, short stories and novels. It includes Toni Morrison, Seamus Heaney, Robert MacFarlane, Alice Munro, George Saunders, Eavan Boland, Anne Carson, Lucia Berlin.

BB: Which books are you planning to read this summer, and where will you be?

UM: I am not sure exactly where I will be as I am moving house. After 25 years in the house where my children were born and raised, I am moving. So I will be in Sligo but mostly on the road between the two houses (all going well as no contracts have been signed yet). At the end of the summer, I will be taking my youngest daughter who has just completed her Leaving Certificate to Boston as she has decided to go to college in the States. When I am not theoretically packing and hauling boxes or knocking down walls and painting, I will be reading Barbara Kingsoliver’s Demon Copperhead. I am completely intrigued by her effort to look at the opioid epidemic and Appalachia in the context of the historical exploitation of that region. Because her book riffs on elements of Dickens’ David Copperfield, I will probably read that next. Then, I intend to revisit short story collections by Anton Chekov, Lorrie Moore, George Saunders, Lucia Berlin and more. I am reading to learn from them but also because I love the form.

BB: Our next issue is on a theme of ‘regeneration’. What does that word mean to you?

UM: Instantly, I think of the capacity to grow again after an injury or trauma. I know it has other connotations such as restoring or reinvigorating, the way we regenerate neighbourhoods. But it’s most powerful sense for me is that resilience, that life force that still pulses despite, maybe even because of, the wound.

Tell Me What I Am by Una Mannion is published by Faber (£14.99 hardback).