Is it Game Over For Country Sports in Britain?

By

2 years ago

What's the future of this ancient way of life?

Are country sports as we know them today coming to an end? Jonathan Young, previously editor of The Field and Shooting Times, reflects on a lifetime spent outdoors as a ‘sportsman-naturalist’.

Main image: Getty

The Future of Country Sports

Sitting at the back of a chest of drawers is a black-and-white photo of me wearing shorts, gumboots and a Guernsey jumper – standard kit for young country lads back in the 1960s. Inevitably, I’m holding a bow and arrow though it could have been a catapult. I know there’s a pen-knife in my pocket because I always carried one from the age of six, as did every other boy I knew.

There aren’t many pictures of me as a youngster because my parents didn’t feel the need to take many. Parental touch was very light then. Children were to be seen and not heard, and preferably neither. The standing instruction was ‘go out and play’ whatever the weather, and so we grew up feral, frequently disappearing for the whole day without any adult supervision.

My playground consisted of a large estuary and surrounding meadows, where my closest friend and I spent our days catching butterflies, newts, lizards and slow worms for our collections, in the manner of Gerald Durrell in My Family and Other Animals. Later, we acquired fishing rods, then air-rifles, then small-bore shotguns and became what used to be termed ‘sportsman-naturalists’.

Neither of them came from a particularly sporting background but my parents fitted in with the country scene, attended the local fox hunt’s Boxing Day jamboree and watched us gallop after the beagles when they met locally. They could also be persuaded to take an evening trip to the local seaside pier, where we ate chips, and caught mackerel and pollack.

My real mentors, though, were local countrymen who befriended me when, like every other teenager, I drank underage in the village cider house. One noticed that I owned a handy whippet cross lurcher, so picked me up for pre-dawn raids on the water-meadow hares. Another showed me the foreshore flight lines for wigeon and mallard. And dear Everard, whose army greatcoat really was secured with binder twine, explained how to set a wire for rabbits and neatly break their necks when the ferrets had bolted them into purse nets.

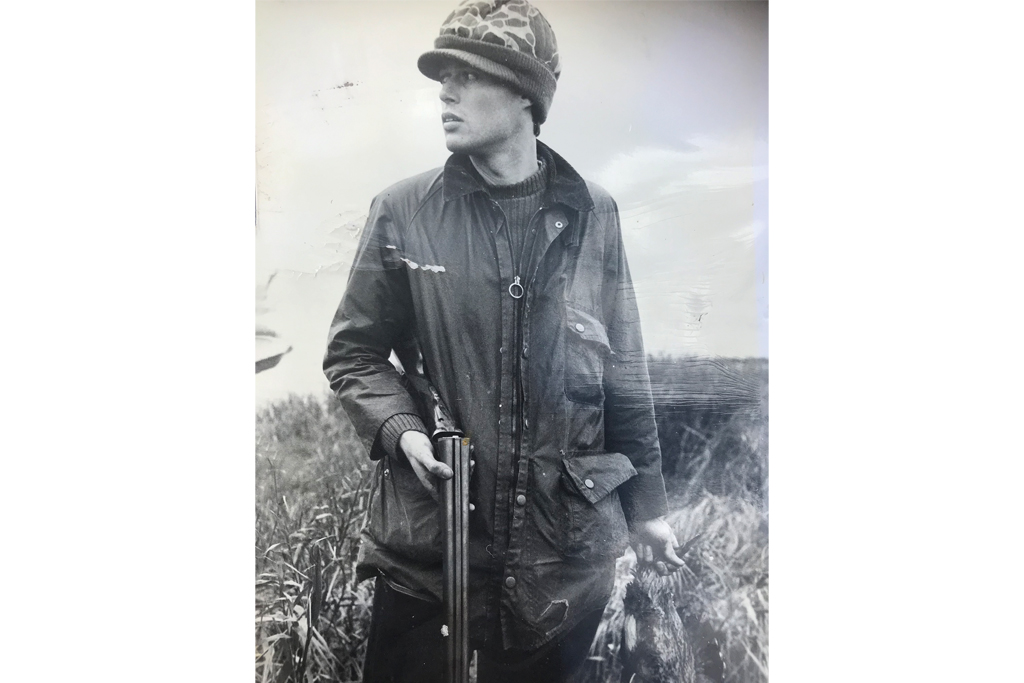

Jonathan Young as a country sports-mad teenager

None of this was unusual then. I could walk along the street, gun in a slip, and the only comment would be ‘Have any luck?’ Field sports were integral to country life. The river was so stuffed with salmon that, although the netsmen took their share, there were plenty left for the gentlemen staying for their customary week at the fishing hotels upriver. Wild brown and sea trout were abundant and the fishing cheap. The wildfowling was free and, with a polite approach, farmers would readily allow rabbit and pigeon shooting on their acres. The only form of shooting that was beyond reach was driven pheasants, which were the preserve of the landed and the small DIY syndicate made up of professional men and artisans.

That sporting landscape, unchanged for centuries, began to alter in the 1980s. The salmon that once porpoised up my estuary were hit hard in the Seventies by ulcerative dermal necrosis, a fatal dermatological disease, and never fully recovered. Water abstraction, slurry leakage and extensive use of nitrogen fertilisers began to damage trout rivers. Hunting came under increasing political and activist pressure from its opponents. And shooting began its transition from a sport to an industry.

The first commercial shoots emerged in the early Eighties. In a way it was more democratic. Anyone with a gun and the wherewithal could now buy a driven pheasant or partridge day and the model spread throughout Britain. An independent survey released in 2014 by the Cambridge-based Public and Corporate Economic Consultants (PACEC) found that two million hectares were actively managed for shooting, that the sport was worth £2bn to the UK economy and supported 74,000 full-time jobs.

There were some unsavoury aspects to this – the demand for ever-bigger bags, (leading to a glut of dead game); the rise of a new type of shooter who had little connection with the countryside or its traditions – but these new shoots brought in millions of pounds to deeply deprived rural areas. Hotels, local services and rural employment boomed. More importantly, the model only worked if the land was managed for game, which meant heather moorland wasn’t buried under trees or sheep, and game cover strips were planted next to monoculture arable crops, giving food and shelter to game, but also songbirds, insects and small mammals.

Not everyone benefitted though. Hunts found that increasing numbers of landowners would not allow them on their land until after the shooting season closed in February. And those who could once rely on friendly farmers allowing them to shoot pigeons and rabbits were now told they had to ask his keeper, who inevitably reserved such perks to reward his beaters and other shoot-support members.

However, driven shooting brought in revenue and it seemed the transition from hedgerow bashing for a couple of brace of pheasants to days when the bag would be tallied in the hundreds was unstoppable.

And then came Covid and the shoots had to be mothballed. Then, after social restrictions were lifted, avian influenza hit Britain and France in 2022. Due to its kinder spring weather, France had become our major supplier of pheasant and partridge eggs, and poults. Those imports were banned and shoots struggled badly to produce birds for the shooting season. This came in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which massively increased energy and feed costs for game farmers.

According to the annual Game Shooting Census, these factors pushed up prices per bird shot to £46 ex VAT – a 31 percent increase in a year. As a result, many driven shoots have closed or scaled down bag sizes and the number of days they sell.

Happily, shooting in its older form is seeing a renaissance. People are rediscovering the joy of walking the hedgerows for a dozen pheasants with a few friends and a couple of spaniels. Farmers are again welcoming pigeon and rabbit shooters.

But hunting as we knew it was banned in 2004. Fishing and wildfowling clubs struggle to attract the Playstation generation. Global warming is changing our marine and land habitats. And Britain is now dominated by an urban culture.

I grew up with countrymen, with rod and gun. They had an intimacy with nature that’s rarer now but still vital if wildlife is to thrive in this crowded isle outside nature reserves.

Jonathan Young was editor of The Field for 29 years and editor of Shooting Times for five