Michael Rosen On His Relationship With His Phone

By

1 year ago

Looking back on a storied career

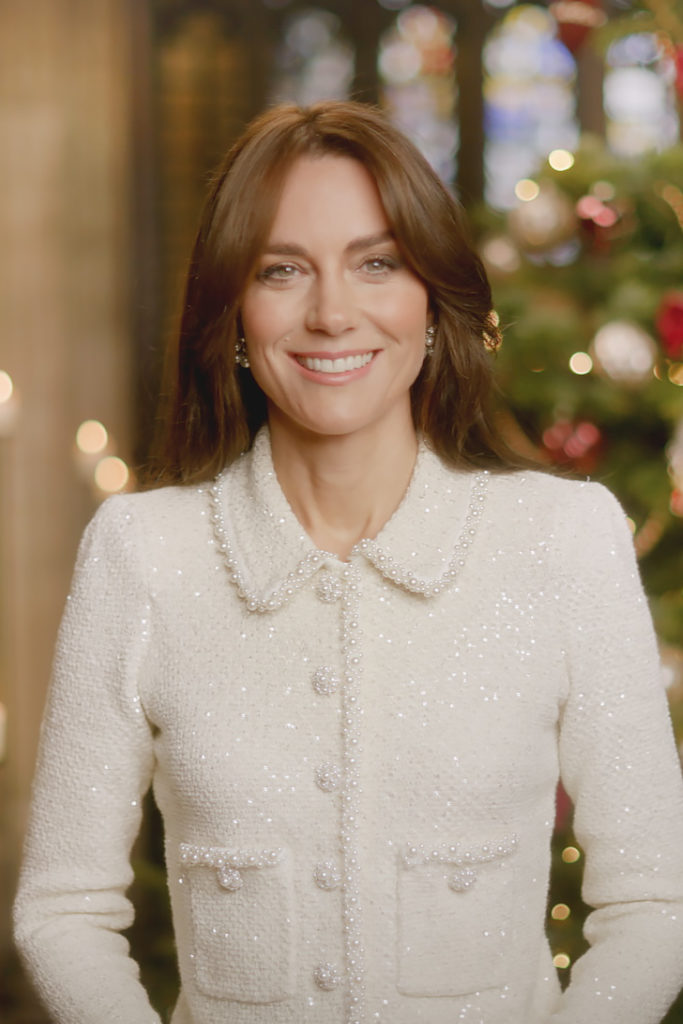

From being the Children’s Laureate to hosting a show on BBC Radio 4, Michael Rosen has had a storied career – and that’s not to mention his writing more than 200 books. Now he is the ambassador for a new smartphone by TCL, which has a matte screen akin to an e-reader. We sat down with Michael to look back on some career highlights – plus what his relationship is like with his phone.

Interview: Michael Rosen

Hi Michael, thanks for joining us today. You’ve recently been announced as the brand ambassador for TCL’s e-reader smartphone hybrid. Can you tell us a bit about that?

Well, I don’t know very much about the technology, but what attracted me to the TCL 50 Pro NXTPAPER 5G was the screen which is matte like paper, so you can use it as an e-reader. It saves your eyes from the soreness that somebody like me gets from staring at screens for a long time, and also stops all the social media pop ups and notifications from distracting you. Obviously I work in picture books, so I’m also interested to see the phone is in full colour, not black and white like we’re used to with e-readers.

Are you an e-reader user, or do you still read paperbacks?

I read a lot of stuff online, either on my phone or on the computer, both for reference but also fiction. I read books quite often professionally for the radio program that I do [Word of Mouth on BBC Radio 4]; sometimes we review books or we interview a writer, so I’d read those books online. But that can be quite tricky if you’ve got pop ups and a lot of information on the screen other than the text itself. The advantage of the TCL is it clears everything off the screen; you’ve just got the text. That’s perfect for me, because I do have a bit of a problem with my eyes post-Covid.

What’s your relationship with your phone like?

I don’t berate myself, tell myself off or chastise myself for using my phone. No, they’re absolute instruments for my life, whether that’s just contacting people or as a reference point. I get quite a lot of calls where I’m asked to comment on something, and I have to dredge something up that I’ve read in my childhood or in the past, so I say, ‘Well, call me back in a minute’. And then I sit there using my phone to access a book or a text or a newspaper article. I do that all the time, sometimes on the hoof, you know, on trains and things.

Do you think social media has changed the way we communicate, too?

It has transformed it in that, if you produce a book, you enter a conversation. A kind of village starts happening around your book. For example, after I published my book about being ill [Many Different Kinds of Love], I was suddenly in conversation with health workers, nurses, doctors, physiotherapists, anesthetists, patients – either emailing me or replying to my posts on social media.

In the past, that was very difficult; authors would have to spend hours and hours on snail mail for the same conversations. So definitely, the digital world is completely different from the old world. It has completely transformed book publishing. Writing for children is slightly different because obviously, you know, usually it has to go through their parents. But even so, I get into conversations with families about my books via social media or email.

I can remember as a child having a book that had been signed by an author because my dad had met him at a conference, and he wrote a little message for me in the book. But it was like a mystery to me. How did my dad meet this author? And then it was kind of magical that I had his name. I’ve still got the book. I remember thinking how special that was.

You’ve got two new books to talk about this season. Let’s start with Totally True (and totally silly) Bedtime Stories – what can readers expect from that?

Yes, this does what it says on the tin! Initially, my publishers said to me, ‘it would be lovely to do a book where the stories were hopeful and true’. And I thought that sounded interesting. How would we do that? So we trawled the internet to find stories that have been published in newspapers and so on, and tell them in a way that is attractive to kids, let’s say five years old plus. These stories could be hopeful, funny and interesting, about very personal, human things, or scientific things. We batted ideas about until we had a body of stories for me to work on. Then I worked on them, and they quite like the way that I talk directly to the child, so that’s the tone I adopted in the book – trying to engage the child. Like ‘Imagine meeting a dinosaur in a river… Well, it nearly happened to some friends!’ So that’s the way I’ve tried to tell the stories and make them so that a parent, when reading them, is sort of talking to their child if they’re reading it to their child. That was what I was motivated by.

And how about Rosen’s Almanac which is a little bit different…?

Yes, this is a book about language, because I do my program on Radio 4 about words and language. My publishers and I were talking about it and the various language things that interest me. And around that week, I had to put out a little call on social media for people to send in their family sayings, the kinds of things that mums, dads, grannies say, and whether it’s little truisms or little mistakes they make. I thought, well, we’ll get maybe 30 or 40 responses. Well, we got nearly 2000 I think, in the end, and we did a program about them. I had a guy who’s a professor of sociolinguistics come on to talk about it with me on the program. And then I realised that could be the spine of the book. So that’s what we did.

So the book is like an almanac – like a diary or a calendar made up of the family sayings that exist mostly in the British Isles, but also beyond. It has turned out to be very funny, and includes sayings from my own parents as well – things like my mum saying, ‘Ask your father what he’s doing and tell him to stop it’. You know, phrases like that. That’s a classic. I love that one.

How does your writing process differ for books like that, versus when you’re writing for kids?

It’s as if you’re in two different rooms. If you think of yourself at home and then in a formal situation, it’s almost as if you’re two slightly different people, isn’t it? At home, you’re probably more slangy, more chatty. Then in a formal situation, you slightly freeze, thinking more carefully about what you’re saying. Writing is just like that: you’re using a different voice, thinking about the audience, putting on a different set of clothes… With Totally True (and totally silly) Bedtime Stories, I was very much remembering myself as a dad with younger children, or being a granddad now. Then when I was doing Rosen’s Almanac, I was thinking, well, I may be with my students at university, or I’m with teachers or colleagues at a conference – the kind of voice I would use when I’m talking in that situation.

Those two books came about in slightly different ways, and you’ve written so many books to date. How do you keep finding inspiration?

I often say this to children, so I’ll say exactly the same to you. Whatever you’ve got, you’ve got your senses. So you can always start from something you’ve seen or heard, tasted, touched, smelled… What did I see today? What did I hear today? And you know, by the end of today, you will have seen and heard a lot of things. Any of those could be starting points for stories.

Your other resource is the things you imagine. So you can just sit, shut your eyes and start imagining and daydreaming. And then there’s also what you remember: when someone was horrible to you, when someone was nice to you, when there was something just quite amazing, or something really very odd or dull or weird.

So that’s what I think of: your five senses, imagining and remembering. Those are the seven springs, if you like, of writing.

We’re Going on a Bear Hunt is probably your most famous book. What’s your favourite book that you’ve written?

I quite often think that my book Quick, Let’s Get Out of Here is my favourite. It is a book of poems, and there are lots of stories about me and my brother, my mum and my dad in there – poem stories. And then also quite a few about my son when he was three. He’s my late son, Eddie. So they’re lovely memories of when he was a very funny baby and a toddler. The book is a nice combination of me and my family growing up and Eddie – a nice marriage. So I do like that book.

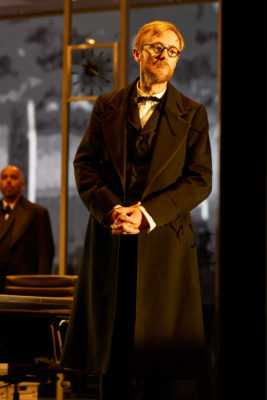

You’ve had such a storied career. What do you look back on as a highlight?

Maybe when I was the Children’s Laureate. After all, when your own profession says, ‘We think you could represent us, and we would like you to do this for two years,’ that’s such an honour. It was a delight that the profession trusted me to do it. I took it incredibly seriously and conscientiously – I really worked at it as hard as I could. I did it from 2007 to 2009, and it was wonderful. It felt very special. The present one is Frank Cottrell Boyce.

DISCOVER

Stay up to date with Michael Rosen at michaelrosen.co.uk