Is It Fair To Cancel Russian Culture?

By

3 years ago

'Surely in desperate times such as these, culture should remain a bridge and a way of keeping dialogue open when political discussion has broken down'

Is the blanket cancellation of Russian culture since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine either fair or sensible? Art writer Ivan Lindsay argues that it won’t help win the war.

Is It Fair To Cancel Russian Culture?

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine there has been a mass cancellation of Russian culture in Europe and the USA. The motivation behind this appears to stem from a belief that, similar to economic sanctions, erasing Russian culture will somehow weaken President Putin’s grip on power and encourage the Russian population to turn against him.

The more extreme supporters of this cancellation also believe there is a savagery embedded in Russian culture, and indeed the Russian soul, that can be found weaving a pattern through Russian art, music, dance and literature, and that this explains Russia’s behaviour in Ukraine. Ukrainian writers and the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry have led this drive to erase Russian culture.

In the Times Literary Supplement the Ukrainian poet Oksana Zabuzhko, best known for her 1996 feminist novel Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex, recently said that Russian literature represents, ‘an ancient culture in which people only breathe under water and have a banal hatred for those who have lungs instead of gills’ and that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine can only be understood by studying the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky, which she defines as, ‘an explosion of pure, distilled evil and long suppressed hatred and envy’.

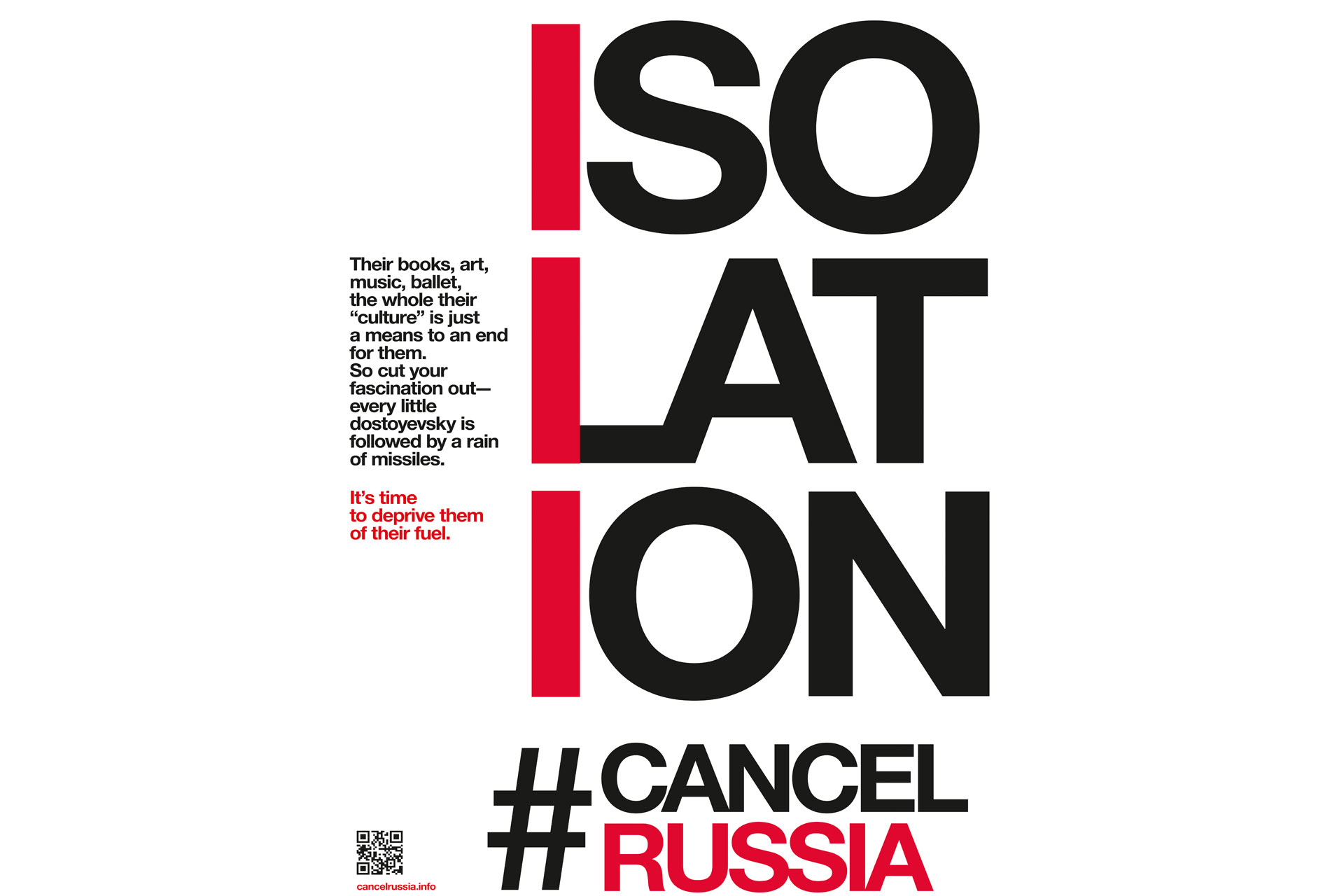

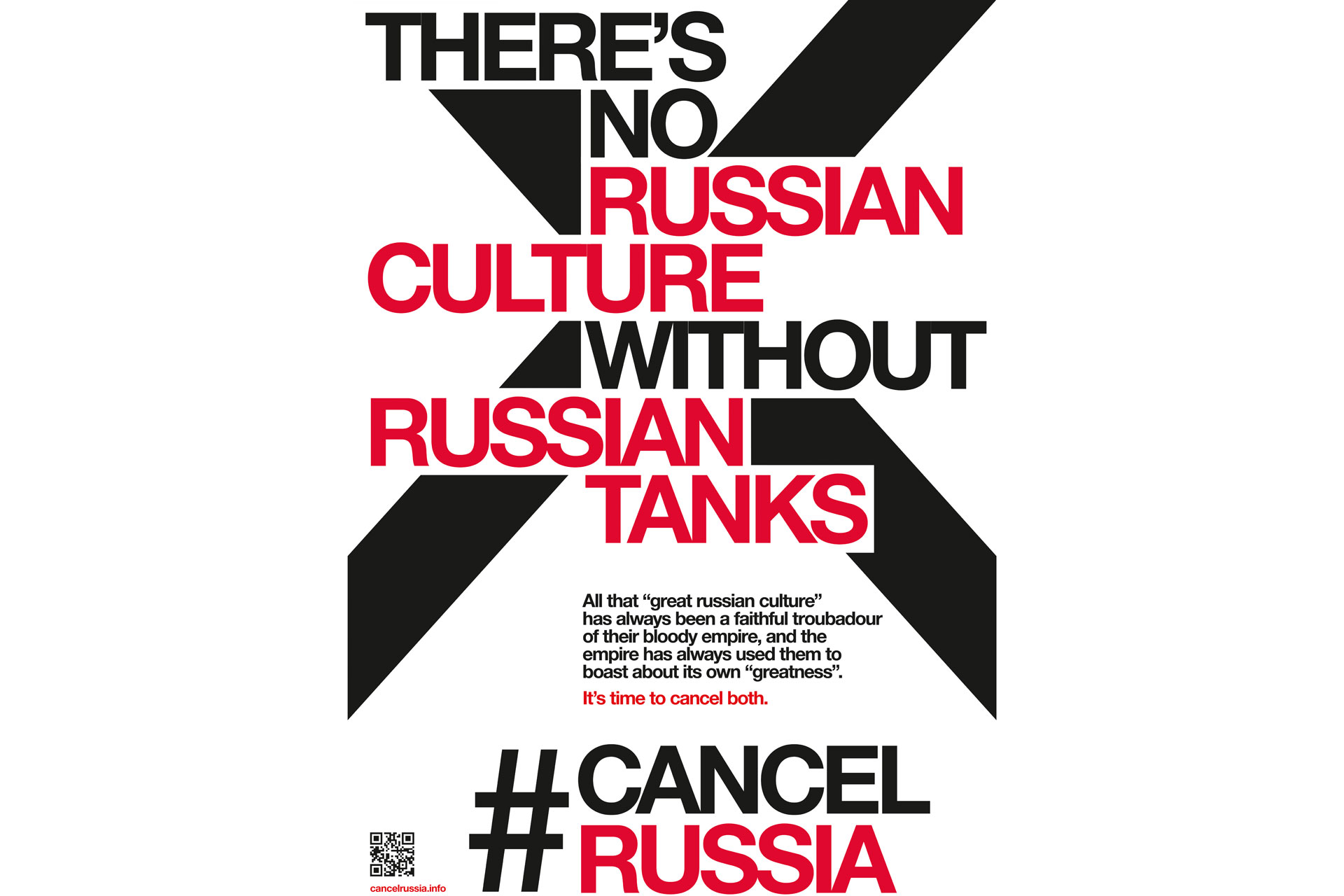

A website called cancelrussia.info provides a set of posters, in English, German, Dutch, French and Italian, advocating the canceling of Russian culture which it encourages you to print off and paste on city walls. In explanation, it says: ‘Russian culture is expansionary and imperialistic in nature… Withhold any funding, support, or even attention you once provided to Russian artists, writers, or musicians. There should be no room for their exhibitions, publications, or concerts. There should be no mention of them in the press… Russian culture today is nothing more than the result of long-term theft of subjugated cultures by the state. Decolonisation of Russia is impossible without the complete cancellation of its culture.’

Oleksandr Tkachenko, Ukraine’s Minister of Culture, joined a group of film directors, musicians, artists and gallery owners calling for the banning of all Russian cultural activities. Early casualties were Russian participation in the Venice Biennale, Wimbledon, the Eurovision Song Contest, the Champions.

League Final, Russian art sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and Formula One’s Russian Grand Prix. The conductor of the Munich Philharmonic, Valery Gergiev, was fired. Anna Netrebko, the Russian soprano, was cancelled from the title role in Puccini’s Turandot at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, which declared that it is ‘no longer engaged with artists or institutions that support Putin or are supported by him’.

The English Royal Opera House cancelled a residency by Moscow’s Bolshoi Ballet company, and the Russian State Ballet of Siberia and the Royal Moscow Ballet were pulled from performances in Northampton and Dublin. The European Film Academy excluded Russian entries from the European Film Awards and the Cardiff Philharmonic cancelled performances of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture and Second Symphony. Russian billionaires, including Victor Vekselberg and Petr Aven, founder of the recently sanctioned Alfa-Bank, have long supported British art galleries, and underwritten exhibition costs, but they are now being removed from boards as museums rush to distance themselves. Tate announced on 14 March that it had severed ties with Aven, and the Royal Academy said on 1 March that Aven had stepped down as a trustee of the Royal Academy Trust and that it had returned his donation towards the cost of the exhibition Francis Bacon: Man and Beast. The Guggenheim in New York also lost its major benefactor in Vladimir Potanin, who recently funded its current exhibition of Russian abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky, when he stepped down as a trustee.

Although many people have privately queried the wisdom of cancelling Russian culture in this way, few are brave enough to say so. It is a facet of cancel culture that it will tolerate no discussion or debate. Once a line is taken by those with a platform and adopted by influencers, journalists and media, contrarian opinion causes outrage as opposed to discussion. Anyone who queries these cancellations is deemed a ‘Putin apologist’ and a supporter of Russia’s actions.

The same people in the West who are advocating this cancelling of Russian culture focus on what Russia is doing and the terrible fallout from this war, as opposed to why Russia is doing it. John J. Mearsheimer, the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor from the University of Chicago since 1982, a leading proponent of the Realist School of geopolitics first developed by Henry Kissinger, says that Russia viewed the expansion of NATO into Ukraine as an existential threat and drew a line in the sand. Mearsheimer says Russia has been invaded through this corridor by the Poles, the Swedes, the French and the Germans, and they repeatedly said they would not tolerate NATO in Ukraine in the same way as the USA would not tolerate Russian troops on its borders in Mexico or Canada.

It is Mearsheimer’s opinion that no one listened to the Russians or tried to understand what they were saying, and when the Russians saw NATO training Ukrainian troops and arming them, while having watched the shelling of Russian speakers in the Donbas for eight years, they acted. Mearsheimer summed up his viewpoint in an article in The Economist on 19 March entitled, ‘Why the West is Principally Responsible for the Ukrainian Crisis’. Recently, the Pope concurred saying the war in Ukraine was, ‘perhaps somehow either provoked or not prevented’ and that NATO had been, ‘barking at the gates of Russia’.

Clearly this terrible war has massive implications for industries such as grain, oil, gas and weapons, and it is thus in some people’s interests to keep the war going. This writer, however, would like to see a ceasefire as soon as possible. Leaving aside why we are where we are, does cancelling Russian culture in this blanket approach actually bring the war closer to an end? Does it put pressure on Putin or the Russian government in any way? Are all these people being cancelled supportive of Russia’s invasion? Many of them, such as the soprano Anna Netrebko, have publicly said otherwise. In addition to its Slavic roots, Russian culture is also influenced by the European Enlightenment and, as such, forms part of European culture. Russian writer Vladimir Sorokin, while advocating passionately against the war, recently told the Financial Times, ‘I think Russian culture will endure. It’s already part of the world’s cultural heritage – it’s hard to do without it.’

Numerous Russian writers, such as Anna Akhmatova, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Osip Mandlestam, have, of course, been anti-war. Leo Tolstoy, who was a committed pacifist, having participated in the Crimean War, has Konstantin Levin criticise Russian military adventurism in Anna Karenina. The futility of war runs through all 800 pages of his epic War and Peace. It makes me wonder whether those who have recently cancelled performances and screen adaptations of his work have actually read it.

Surely in desperate times such as these, culture should remain a bridge and a way of keeping dialogue open when political discussion has broken down. In addition, these cancellations fuel Russia’s Slavophile tendencies, already resentful and suspicious of the West, and thus rally Russian support of their leadership. In the words of the Russian pianist Aleksandr Melnikov, ‘When pressed against the wall, the Russians only cluster tighter around the leadership’.

Rather than a knee-jerk reaction lashing out at all Russian culture as a way to object to this war and hoping that it might somehow weaken Russia’s war plans, it might be better to let it continue, keep the door open, and acknowledge that it is part of our own collective past and future. The conceptual Ukrainian artists Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, while voicing their objection to cultural sanctions, said, ‘Cultural connections are things that bring people together when politicians fail’.

READ MORE:

Fundraising Events For Ukraine / Art on a Postcard’s New Mini Auction Will Support Ukraine