Peek Into The Modern Day Ball

By

2 years ago

It's now a very different ballgame

Do the pomp and peacockery of the aristocratic ball have any relevance to our lives in the 21st century? Rosalyn Wikeley heads to Monaco to observe the modern day ball’s beau monde letting loose on the dance floor.

Does the modern day ball exist?

The end of the British deb ball

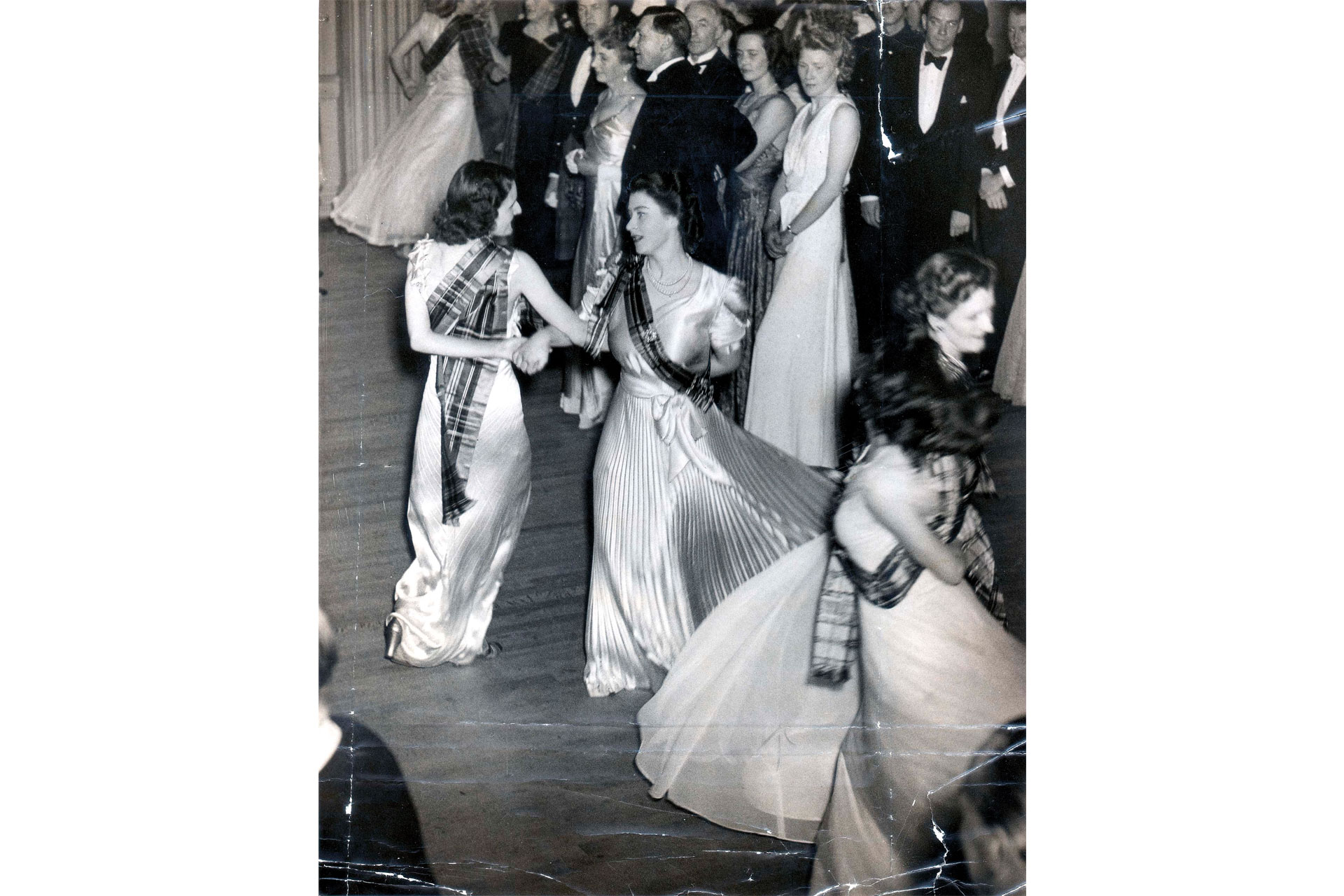

‘We had to put a stop to it. Every tart in London was getting in.’ Princess Margaret’s cutting, if not revealing, defence for ending Palace débutante balls confirms the high society game: the preservation and frequent pruning of an elite, as if keeping a small, but perfectly-formed garden in check… no weeds.

In some ways, the late Princess’s quip marks the demise of an indomitable pillar of patriarchal society: where aristocratic girls were paraded like bejewelled cattle for salivating gentlemen and used as pawns in their parents’ socio-economic chess games throughout ‘the season’. But also, and perhaps more deliciously, it touches on an elitist impulse that lies deep in the less honourable chambers of human nature. Balls will assume various incarnations throughout the decades, but this impulse endures, spurred on by champagne-fuelled cavorting and climbing opportunities.

The final blow to the official British deb ritual was dealt by the late Queen Elizabeth II, who oversaw the last white-gloved hurrah in 1958. As feminism gained momentum and postwar Britain was forced to tighten its purse strings, she symbolically and quite prudently put an end to the whole ordeal. Various deb offshoots rushed to fill the void (such as the revived Queen Charlotte’s Ball of 1780, which the Duke of Edinburgh reputedly described as ‘bloody daft’), but the fairy dust was lost with the royal stamp, consigning most deb affairs to the woeful realms of gimmick or big moneyed, American-style galas.

These débutante dos are, however, only one iteration of the ball, whose etymology lies in the Latin ‘to dance’. Stripped down and a ball (be it a modern day ball or the thing of the past) is exactly that: one big party where an edited few cut some choreographed shapes. Then there’s the decadence, the high society hobnobbing and the spectacle.

No one does this better than the blue-blooded Europeans, whose ball pedigree is unrivalled – from Charles VI of France’s debauched 14th century masquerade balls to the decadent and equally scandalous Venetian rendition which faded into desperate replicas with the fall of the Republic. Where Britain still dines on its bygone era of the Duchess of Devonshire’s hedonistic soirées and Jane Austen’s orderly waltzes and quadrilles, European balls seize on a distinctly more flamboyant theme and are generally considered to be much more fun.

Inside the mega-luxe Bal de la Rose

Bal de la Rose is no exception. First held by Princess Grace of Monaco in 1954 to raise funds for her foundation for sick children, it’s up there with the Ghillies Ball (Balmoral’s annual bash since Queen Victoria’s reign), Anna Wintour’s Met Gala and Vienna’s opulent Hofburg Silvesterball for exclusivity factor.

This year’s ball not only coincided poignantly with the 40th anniversary of Grace Kelly’s death, it also marked Christian Louboutin’s debut as artistic director, following a decade under the flawless eye of the late Karl Largerfeld. And along with the society swans, the international jet set and the odd celebrity flocking to the prestigious Salles des Etoiles, I bagged myself an invitation: a thick, elaborately illustrated card promising royals, roses and red-soled stilettos.

It’s this typically Monégasque concoction of Grimaldi royalty, the jet-setting cognoscenti and celebrity that lends Bal de la Rose its mystique and longevity. It’s not a relic of a bygone, feudal age, nor a garish gala awash with cheques, it’s where various pockets of 21st century power coalesce – this year amid a wildly imaginative scene of pinks and lacquer reds.

Christian Louboutin’s bold, Roaring Twenties cabaret vision saw no less than 14,000 roses and 900 chaises Napoleon III golden chairs line the tables, all of which were perfectly placed so no diamond clad guests need strain for a glimpse of Dita Von Teese’s risqué burlesque act. Curiously, the royal table appeared unphased by the night’s abundance of nipple tassels and erotic frolicking that would have crossed all lines of decency for the British crown. Indifference to nudity is hardly surprising from a principality propped up by casinos and cabaret.

Indeed, the Grimaldis embraced the kitsch cabaret spirit with standing ovations and brightly coloured ball gowns. These later spun across the dancefloor to Donna Summer’s I Feel Love, which, in the absence of Austen-age formalities, became a free-for-all. Punters encircled the royal clique like bopping fruit flies, feigning insouciance as they edged in ever closer. Pierre and Beatrice Casiraghi, seemingly oblivious to the advancement and really anyone in their frenzied path, twirled in rapture, while Princess Caroline chatted with Christian Louboutin, who she helped put on the map all those years ago as a little-known Parisian shoe designer.

All the privilege and couture gowns began to blur into a scene not far removed from a high school prom or a louche, post-midnight wedding. You could spot the fledglings, anchored to their tables in bemusement, foxtrot expectations dashed. Well-oiled veterans formed tight circles across the dance floor: a safe space in plain sight.

The verdict

Much like Bridgerton’s Lady Whistledown, I obliged for a few crowd pleasers before retreating to the sidelines to absorb the fanfare. The appetite for high-octane revelry was manifest from my vantage point, and the room was charged with the knowledge that royals and celebrities were but a shoulder shimmy away. Here are feudal currents of the deb ritual in a different guise, a social restlessness that reaches fever pitch in the top echelons of society. After all, power and privilege cease to exist in a vacuum, they demand a dance floor, or indeed, a ballroom.

In Brothers Grimm-style, the magic of the Bal gripped the principality for days and lingered on in the Grimaldi Forum, where Christian Louboutin’s creativity was given yet another stage with his own exhibition. Guests arrived like sequinned pilgrims from yachts and helicopters before making a beeline for Mont Carlo’s Grande Dame, Hotel Hermitage. Once ensconced with macarons and tea, they readied themselves in marble, Belle Époque rooms with ‘glam squads’ matching lip shades to gowns. Nursing a hangover the following morning, Mrs Bennet-style with egg yolk on the Hermitage spa’s terrace, I spotted a few ball guests suffering similar ailments, their headaches soothed only by a bout of fresh Bal gossip and the world’s most extravagant green juice. Man of the hour Christian Louboutin swung into the lobby, much to the delight of the ton.

Modern day balls may not be imbued with the same level of intrigue that they once were – they lost their monopoly on peacocking long ago, as the aristocracy began to lose their grip on guest lists. But in the wake of the pandemic, there is a renewed appetite for dramatic dressing and pomp; for a spot of formality easing into a night of frivolity. Or, put plainly by our friend Mr Louboutin, ‘people need to mingle, stare at each other, kiss and make beautiful memories’.

Peek inside the modern day ball