Van Gogh: Poets And Lovers Is A Magical Journey Through The Artist’s Mind

By

7 months ago

The National Gallery's first Van Gogh exhibition in history is well worth the visit

Two centuries after The National Gallery’s foundation, and one century since it acquired Sunflowers (1888), Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is the first exhibition dedicated to the artist in the museum’s history. Delving into his poetic imagination – and the themes that recur because of this exuberant mind’s eye – Olivia Emily gets an early glimpse at the painter’s magic.

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers At The National Gallery, London

Vincent van Gogh

Starry Night over the Rhône, 1888

Oil on canvas, 72.5 × 92 cm

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Donation sous réserve d’usufruit de M. et Mme Robert Kahn-Sriber, en souvenir de M. et Mme Fernand Moch, 1975

Photo © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

What better way to enter its third century than for The National Gallery to make a triptych the focal point of its landmark exhibition? Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is part of the wider NG200 scheme of events – and it’s clear the British institution has pulled out all the stops: more than 60 of Van Gogh’s idiosyncratic pieces are on display, most on loan from world-famous institutions and small private collections across the globe. The lights are slightly dimmed for protection purposes, but the energy is palpable nonetheless: everyone is excited to be here.

The central triptych in question is reunited for the first time since the paintings were composed in Van Gogh’s studio in 1889; it takes up the whole back wall of Room 5, about halfway through the exhibiton. It’s the first time Sunflowers (1889) has left the United States since it was acquired in 1935. Its older sibling, Sunflowers (1888), was kept in the family after Van Gogh sent it to brother Theo in 1889, before it was acquired by the National Gallery in 1924; the two pictures have never before been exhibited together. The monumental reunification takes up the back wall of one of the exhibition’s six rooms, and puts into perspective, just for a moment, how far this expressive artist’s impact reached even just a handful of years after his death, despite never really seeing commercial success in his lifetime.

The central painting, La Berceuse (The Lullaby) (1889), depicts an older woman holding a cradle cord against a stylised floral background, suggesting a cradle beyond the limits of the frame; ‘Berceuse’ translates to ‘lullaby’ or ‘she who rocks the cradle’. It would suit a fisherman’s ship, Gogh thought, rocking the sailors to sleep, comforting them with a sense of youth, protection, home – despite being far from it. It would help the men in ‘their melancholy isolation, exposed to all the dangers alone on the sad sea […] experience a feeling of being rocked, reminding them of their own lullabies,’ Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo. Quaint (if heartfelt) aspirations, indeed. So how would he feel about this very sturdy hanging in the UK, miles and miles across the sea from his Dutch motherland, his French homeland – the centre point of what’s anticipated to be The National Gallery’s most eminent exhibition of the year so far?

Vincent van Gogh

Sunflowers, 1888

Oil on canvas

92.1 × 73 cm

© The National Gallery, London

This doesn’t mean Van Gogh didn’t think about success: popping up through Poets and Lovers are quotes from the artist describing his works, their impetuses, and who might be the next big thing. This is the note the exhibition ends on: ‘The painter of the future is a colourist such as there hasn’t been before,’ Van Gogh wrote to Theo in 1888 when he moved to Arles. Over the next two years, he would produce a body of work totally bewitched by the nature surrounding him: public gardens, parks, weeping trees – even the lush gardens of the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole hospital Van Gogh checked himself into in 1889. His work now somewhat of a diaspora, long estranged pieces come together at Poets and Lovers to elucidate the romantic themes spinning in the painter’s mind: duos, vibrant gardens, skies swirled with clouds fluffy and stormy alike.

In 1889, Van Gogh hoped to display a selection of his works as a cohesive group at the Paris Exposition Universelle 1889. The 1867 edition, indeed, inspired Van Gogh to no end thanks to the presentation of Japanese artwork for the first time; the artist’s scratchier depictions of nature, renderings in quill and reed pen of the shrubs, trees and rocky outcrops of Montmajour, Arles and the asylum, are sparser, inspired by the Japanese woodblock prints the artist had been avidly collecting. Garden with Weeping Tree, Arles (1888) is strikingly soft, juxtaposed by the same tree in Weeping Tree (1889) which is even darker, straight lines pulling the storm cloud like canopy down to earth.

Vincent van Gogh

Landscape near the Abbey of Montmajour, 1888

Chalk, ink, pencil, 48.3 × 59.8 cm

© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

These natural spaces conjured magic in the artist’s mind, who envisioned the public park in front of the famed Yellow House as a Poet’s Garden haunted by Italian Renaissance poets Petrarch and Boccaccio, while his whimsy continued at the hospital, the overgrown garden becoming a secluded site for lovers, a portal of euphoric exploration. The towering trees dwarfing his asylum are rendered in graphite, watercolour and Van Gogh’s characteristically thick oil paints. A place of contrasts, at other times, this garden represents suffering, illustrated with muted tones, scratchier pen work. Van Gogh is perhaps best known for his impasto as well as his penchant for vibrancy, for yellow – but the real stars of the show are these muted moments – unexpected heavyweights, beige and blush paper showing through expressive ink.

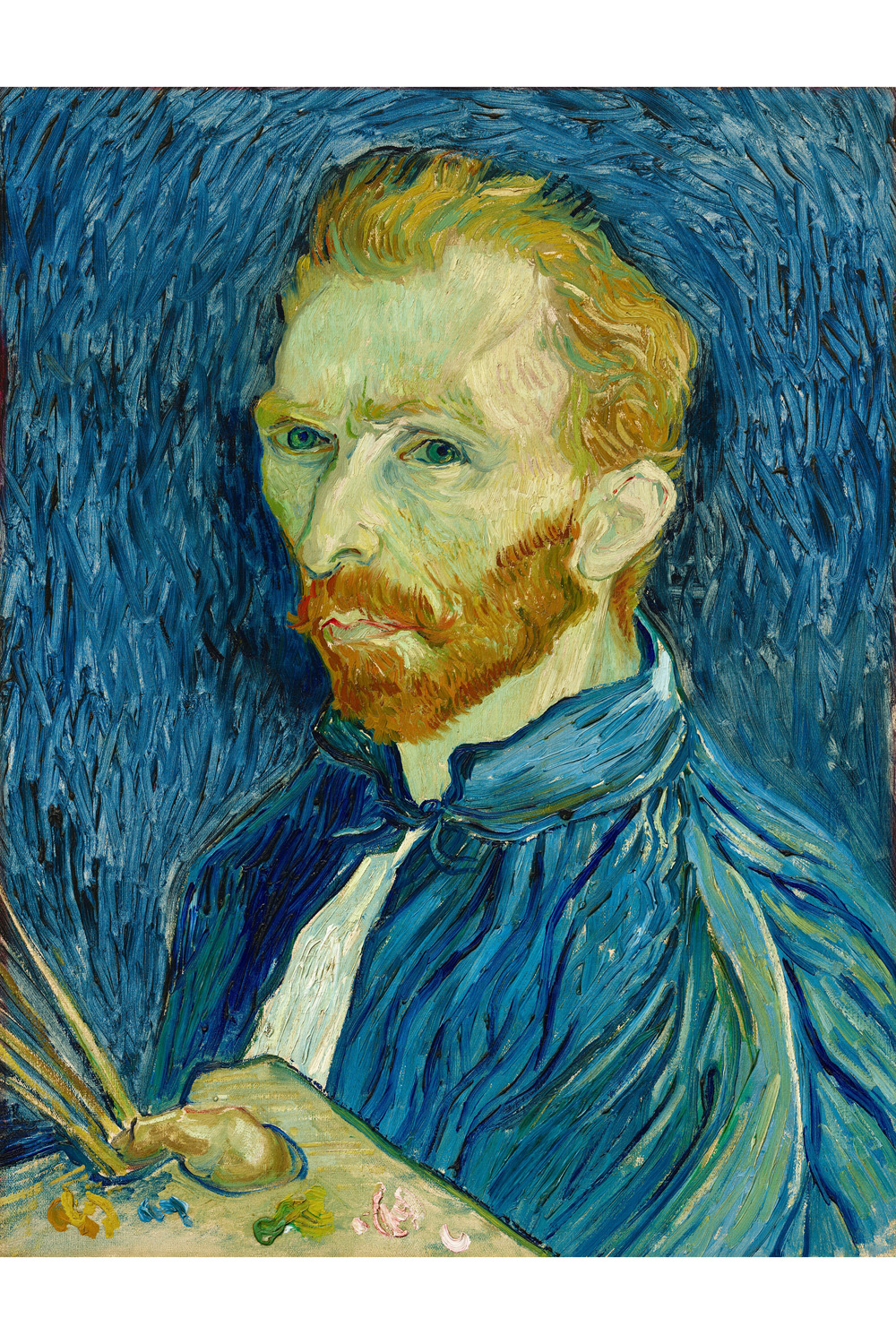

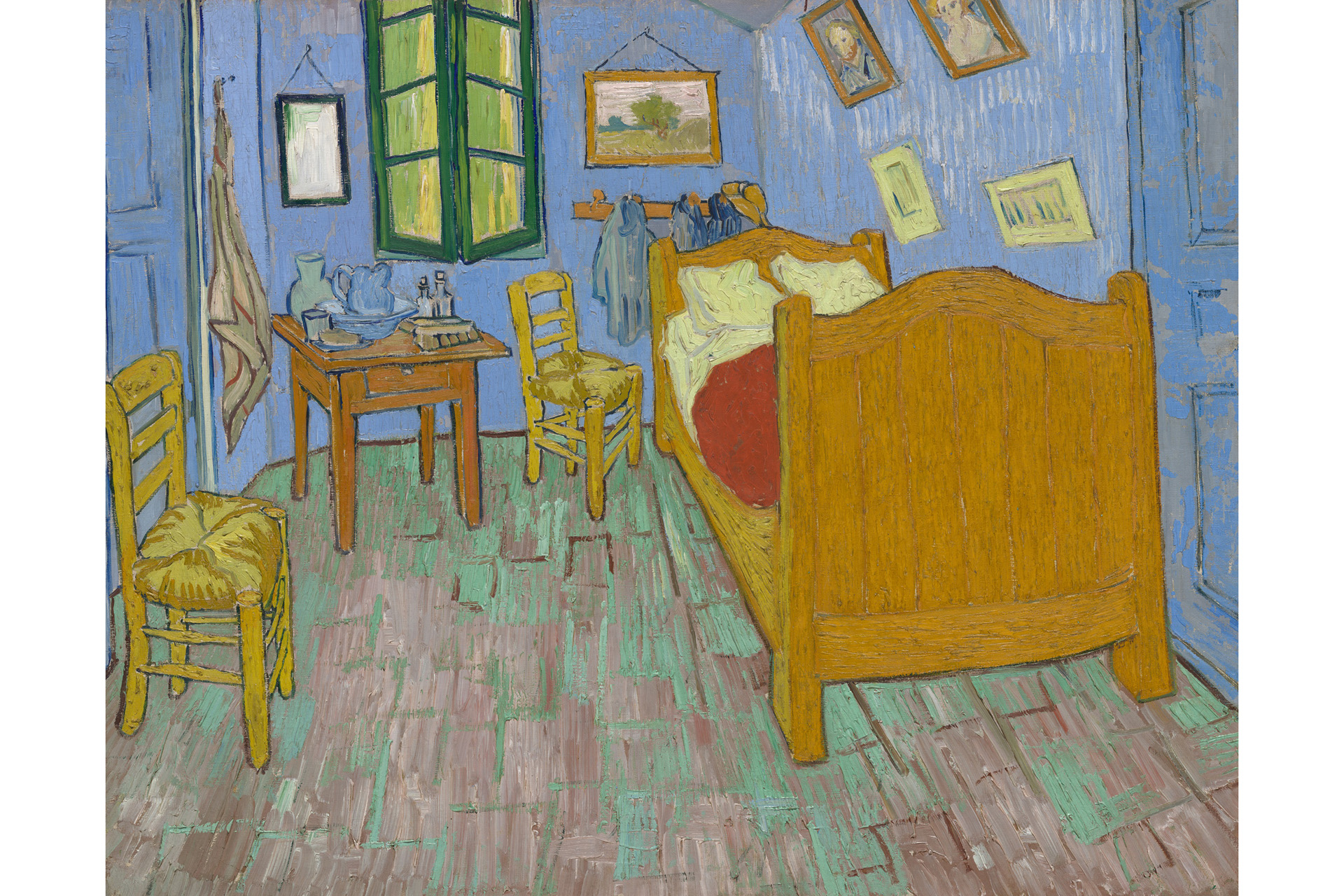

These asylum paintings creep back towards the artist’s well known vigour after a mental breakdown, but it is Arles that fascinated him most – nature’s movements, spirals and vitality. As the exhibition progresses, we return to the almost radiant vibrancy, the impasto, the swooshes of colour across the canvas. We explore familiar ground: paintings depicting the Yellow House, the artist’s thoughtfulness for display and decoration once again considered, with his recent Self Portrait (1889), complete with paint palette in hand, reappearing in The Bedroom (1889), hanging on the wall above the yellow bed. And it’s this consideration that underpins the whole journey: we see the same compositions repeated, tweaked, re-energised, re-considered from new perspectives and through new filters – piecing together the enigmatic process that has underpinned some of history’s most recognisable compositions, and imbued them with magic.

Vincent van Gogh

The Bedroom, 1889

Oil on canvas, 73.6 × 92.3 cm

© The Art Institute of Chicago

What’s On Display?

From private collections to large collections overseas to The National Gallery’s acquisitions itself, Van Gogh’s work has come from all four corners for Poets and Lovers. Highlights include:

- Starry Night over the Rhône (1888)

- Sunflowers (1888)

- Sunflowers (1889)

- La Berceuse (The Lullaby) (1889)

- Van Gogh’s Chair (1888)

- The Bedroom (1889)

- Self Portrait (1889)

- The Yellow House (The Street) (1888)

- Portrait of a Peasant (Patience Escalier) (1888)

- The Sower (1888)

- Field with Poppies (1889)

- A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (1889)

Where Is It?

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers is on display in Rooms 1–8 at London’s National Gallery (Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN).

When Is It Running?

Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers runs from 14 September 2024 until 19 January 2025.

How To Get Tickets

Exhibition tickets are priced at £24pp and are on sale now at nationalgallery.org.uk, with bookings currently being taken up to 13 October 2024. National Gallery members can visit for free.