The Best Watchmakers Of Today

By

1 year ago

Who are the most iconic watchmakers working today? Simon de Burton finds out.

The 21st century renaissance of traditional watch making has been astounding: until the mid-1990s creating beautifully crafted timepieces in the old-fashioned way remained a minority interest after the ‘quartz crisis’ threatened to kill off clockwork for good.

Paradoxically, the success of the utterly democratic Swatch – plastic-cased and quartz-powered – produced money needed to revive ailing grand names and return mechanical watchmaking to the fore.

Since then, helped by the internet, luxury watches have boomed, in both sales and the number of makers, as historic ‘maisons’ are joined by contemporary independents at the mid-to-high end and young brands offering well-made models for under £1,000. Watchmaking has only grown strong through individual players who are now recognised for their game-changing contributions in different areas: Jean-Claude Biver breathing life into Blancpain (the oldest surviving name) before turning Hublot from a loss-maker into a global horological phenomenon; Max Büsser spotting a market for radical designs in low numbers and founding MB&F to create far-out watches for the few, working with exceptional makers; or Oris CEO Rolf Studer putting his affordable brand at the vanguard of watchmaking’s sustainability crusade.

Here we shine the spotlight on seven of the best watchmakers making their mark, equally diverse in aims and methods.

Seven Of The Most Iconic Watchmakers Of Today

Thierry Stern

Many regard Patek Philippe as the most prestigious watchmaker – and CEO Thierry Stern as possibly the industry’s most important individual since he took over from his father, Philippe, in 2009. Stern has instigated the creation of a new $600m manufacture building and pushed output from about 40,000 watches in 2010 to a believed 70,000 today. Neither move has failed to prevent demand vastly outstripping supply. One example of 170 $53,000 steel-cased Nautilus sports watches with ‘Tiffany blue’ dials, made to mark the jeweller and Patek’s long association, fetched $6.5m at auction. Despite achieving his aim of attracting younger, hipper buyers, Stern has dramatically streamlined Patek’s retail network from 750 stores to little more than 250 today. The thinking is to make more watches available to the better-performing outlets and, since UK turnover alone has risen from £60m when Stern took over to £185m today, it looks like he’s done the right thing.

Richard Mille

Frenchman Richard Mille founded his brand, in collaboration with Audemars Piguet, in 1999 after setting up watchmaking for jeweller Mauboussin. His vision was to make watches engineered to Formula One car standards, with highly shock-resistant movements, ergonomically designed cases and open dials revealing intricate mechanisms. And the price? That was irrelevant to Mille, but they were always going to be expensive. Very expensive. In 2001, his first trading year, Mille sold 17 – at CHF 200,000 apiece. Now he produces about 5,500 watches per year, some of which cost more than £1m. And yes, there’s a waiting list. With his audacious business plan, uncompromising attitude, and cutting-edge materials and techniques, Mille is a superstar with products coveted by the (very) rich and famous. But, despite a stratospheric rise to success, Richard Mille – man and brand – maintains a playful side. Look at the RM 88 ‘Smiley’ tourbillon launched this summer, adorned with miniature sculptures of ‘happy’ symbols such as parasols, rainbows, pineapples. Oh, and hanging from its yellow rubber strap is a playful price tag of £1m.

Nick and Giles English

In 2002, when Nick and Giles English made initial plans to found Bremont, their mission was to reinvigorate the British watch industry both by assembling timepieces and making as many components as possible in the UK. Twenty-one years later, they seem well on the way, with Bremont now headquartered at The Wing, an avant-garde manufacturing facility near Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire. The 35,000sq/ft building is a state-of-the-art, eco-efficient and fully integrated ‘manufacture’ capable of producing up to 50,000 finished watches annually – considerably more than any British watch brand since the demise of Smith’s in Cheltenham over 50 years ago. Last year the brothers unveiled Bremont’s first series-produced watches powered by in-house movement ENG300. We’d say that’s ‘mission accomplished’.

Michel Navas

Those with a passing interest in watches may never have heard of Michel Navas, but to horophiles he’s a living legend. In the game for over 40 years, he has worked with blue-chip names such as Patek Philippe and Gérald Genta and collaborated with Franck Müller on the insanely complicated movement of the Noughties-defining ‘Crazy Hours’ watch. In 2004, Spanish-born Navas decided to monetise his skills as a designer of complicated movements by setting up the design and production business BNB Concept – ‘N’ for Navas and the Bs for fellow co-founders Enrico Barbasini and Matthias Buttet. Navas and Barbasini then set up La Fabrique du Temps in 2007 and created the Laurent Ferrier tourbillon and micro-rotor winding mechanism. After five years, they were approached by luxury goods giant Louis Vuitton, which wanted to up its watchmaking game and, through LFDT, could buy a ready-made reputation. Navas remains in charge and has put Vuitton on the map as a leader in complex, imaginative automaton watches. And, as the ‘new’ Tambour demonstrates, we ain’t seen nothing yet…

Georges Keen

This cornerstone of the Swiss watch industry started 31 years ago with TAG Heuer before, in 2002, becoming CEO of IWC, where he spent 15 years transforming it into one of Richemont’s most successful dial names. In 2017, he resigned as Richemont’s ‘head of watchmaking’ to become CEO of Breitling, then recently bought by private equity group CVC Capital Partners in a $900m deal. Kern has streamlined Breitling, upped its appeal to a younger audience by recruiting celebrity ‘squads’ in surfing, athletics, aviation and exploration, and eschewed trade shows in favour of revealing new models at independent spectaculars. Deals with hip motorcycle-associated brands have enhanced Breitling’s cool factor, and provided action man Kern with a new hobby alongside his love of cycling and cinema.

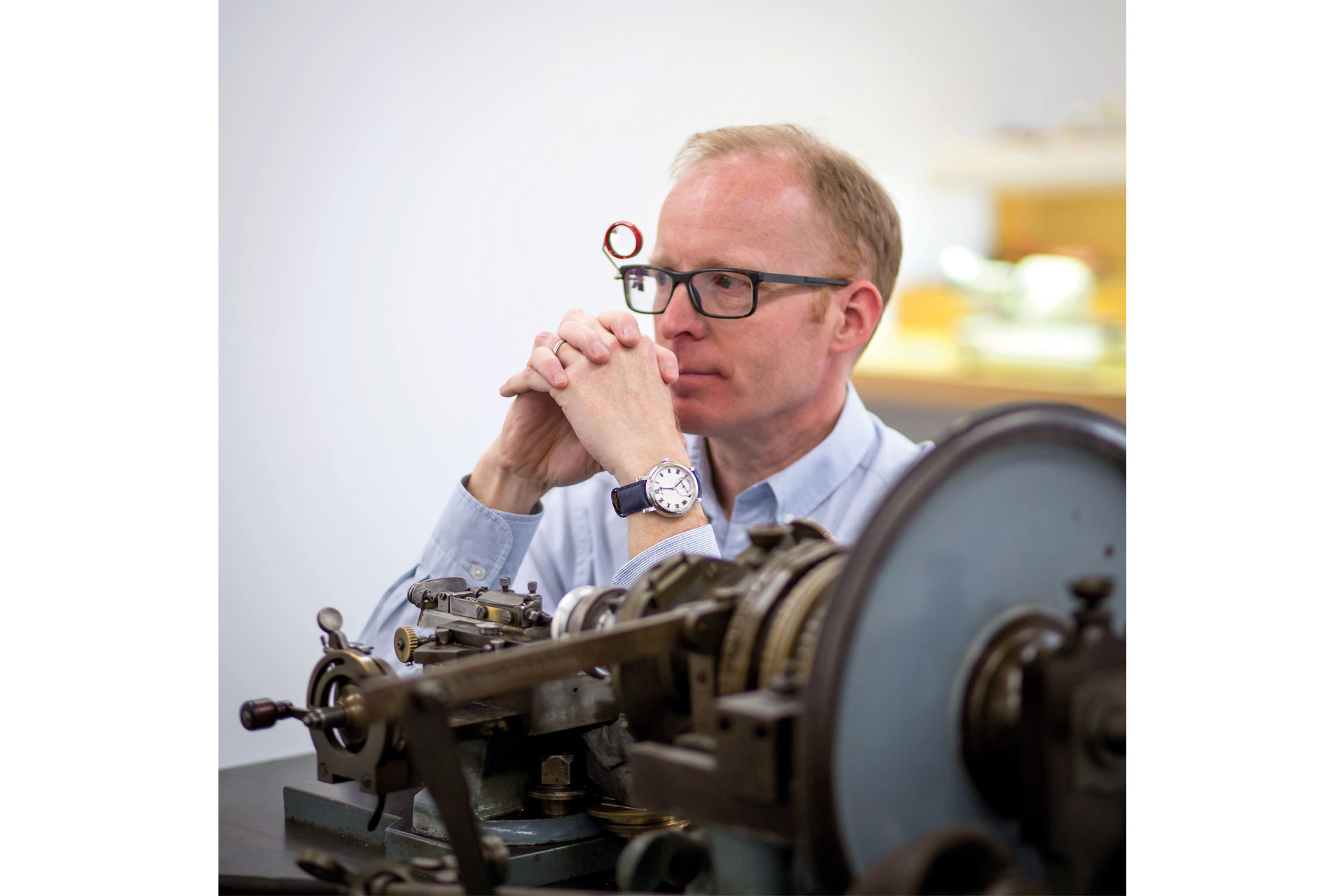

Roger W Smith

George Daniels was perhaps the greatest watchmaker of the 20th century – and now his only apprentice, Roger Smith, seems to be taking over the mantle, living and working on the Isle of Man, where he moved 25 years ago to work with Daniels. In 2001, early in the mechanical watch revival, Smith founded his own dial name to perpetuate ‘the Daniels method’ – making watches entirely by hand, finished traditionally with characteristic features such as frosted movement plates and silver, engine-turned dials. Smith has no ambition to make more than ten watches per year, because he wants every one to be perfect. He was chosen by the Cabinet Office to produce a one-off watch for the Government’s ‘Great’ campaign showcasing British skills; he has been awarded an OBE for his contribution to art and science; he has scooped a Walpole award for outstanding British craftsmanship and his order book is full for at least the next six years. This suggests perfection may, indeed, have been achieved. Why else would someone have paid £3.8m for Smith’s Pocket Watch Number Two at a Phillips auction in June, setting a record for a British-made watch?