African Reins: Visiting Botswana on Horseback

The best way to spot game in Botswana is on horseback. Rosalyn Wikeley saddles up...

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

Boasting the highest concentration of wildlife in Africa and plenty of unpopulated wildernesses, there is no better way to visit Botswana than on horseback. From the Kalahari Desert to Okavango Delta, Rosalyn Wikeley saddles up for the ride of her life…

Botswana is having its moment. With the release of Amma Asante’s A United Kingdom, starring David Oyelowo as Botswana’s first president, adventure-seekers are hooking on to the fact that Botswana hosts some of Africa’s last remaining unpopulated wildernesses, with the highest concentration of wildlife to be found anywhere on the continent. And there’s no better way to see it than on horseback.

Giddy-up, riding with giraffe at Royal Tree Lodge

Ride Botswana, founded by David and Robyn Foot, specialises in bespoke, luxury riding safaris, championing substance and immersion over tourist pomp. They have successfully combined their passion for the bush and horses with a wealth of safari experience, offering guests the chance to discover terrain that’s inaccessible to vehicles or walking parties. Their mobile safari operation ranges over some of Botswana’s most prestigious lodges and parks, from the famously remote Jack’s Camp in the Kalahari Desert to the plush Royal Tree Lodge on the Thamalakane River and recently, the newly launched ‘Delta Ride’, fly camping in the enchanting Okavango Delta. I joined them for seven days in the saddle.

Thamalakane River Ride

This is where I eased my way into both saddle and safari. Operating from Royal Tree Lodge, a small ten-tent camp nestled in 400 acres of riverine trees and acacia woodland, the reserve is jam-packed with lion-free wildlife. We met zebra, springbok, giraffe, eland, oryx or ostrich, blissfully undeterred by the equine presence.

The magnificent Thamalakane river – a short canter away- is David and Robyn’s backyard. Coated in waterlilies, the inviting water is in fact home to crocodiles and hippos, which you can watch from safety with a tipple on the veranda. The next day, cantering along the river and into the reserve, we stumbled upon bushbuck and ostrich eggs.

Later, having peeled off my jodhpurs and stepped into the outdoor bamboo shower, I returned to the Thamalakane, this time on a motorboat for sundowners. Eleven hippo cut our sunset journey short, their pink eyes poking out of the calm evening water.

The Delta Ride

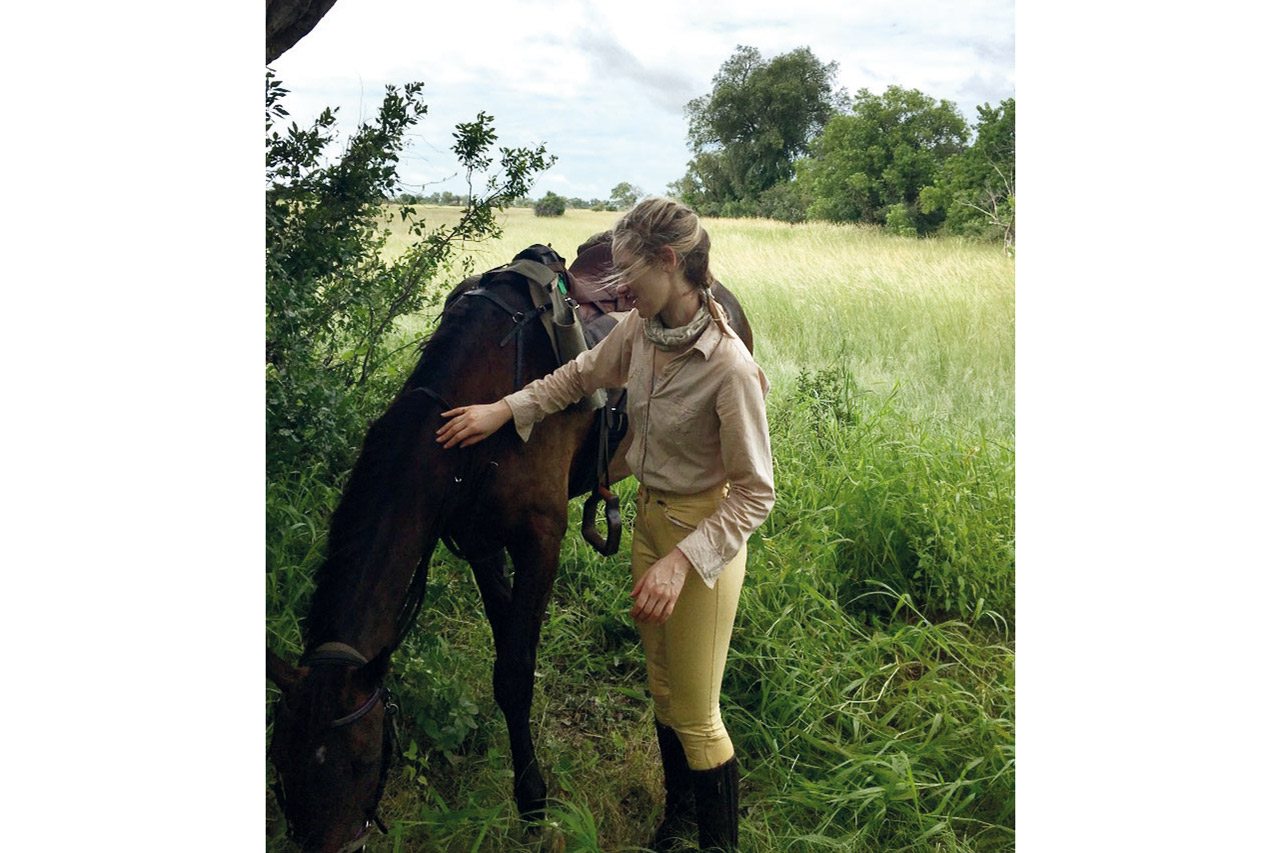

Rosalyn and ‘Socks’ take a breather in the Okavango Delta

Recently declared the 1,000th World Heritage Site, the Okavango Delta is a horse rider’s Eden. As the floodwaters spread down into the Kalahari sands, the herds and birdlife follow, making for spectacular equestrian theatre. Rather than a permanent riding camp, a lightweight mobile camp is transported by a flotilla of mokoros (traditional dugout canoes), which are poled by members of the local community who live on and know the fringes of the Delta intimately.

While the men set up camp under an enormous sausage tree, Robyn unpacked the silverware and applied her culinary prowess to a makeshift table. We devoured succulent steaks cooked over a log fire, admiring the cosmic ceiling above us.

Time out from the saddle

Next day, we loaded up the horses and set off, the team wired for another adventure. As we dipped in and out of yet another soggy hippo tunnel, our guide spotted elephant ahead. My horse’s ears pricked up, two warthogs leapt out of the grass and fish eagles circled above. We barely trotted that day, humbled to a gentle walk by the beauty of our surroundings, an almost prehistoric setting with palm trees, long grasses and colossal termite mounds breaking the horizon.

The Kalahari Desert Ride

Jack Bousfield, the bold explorer and avid croc hunter, embarked on a lifelong love affair with the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans in the early 1970s, before turning to conservation. Following his death in an aeroplane crash, his son Ralph with his wife Catherine Raphaely, established Uncharted Africa, with Jack’s Camp in his name.

Ride Botswana has teamed up with them to offer three or five-night horse safaris at both Jack’s Camp and Camp Kalahari (Jack’s slightly less excessive, yet equally alluring younger sister). The five-night option combines three nights at Camp Kalahari with two-nights fly camping out on the Makgadikgadi Salt Pans, and it was there that we pulled up at the desolate island (there was a storm to contend with as well as a zebra migration), adorned with palm trees and exquisite tents. ‘This place is normally bone dry,’ remarked David. High and dry season is May to September, if you’re not moved by tempests.

Riding with the zebra in the Kalahari Desert

Rain nothing but a distant, noisy memory, I awoke in a four-poster Victoriana, a tent of curiosities and shortbread biscuits. In the morning, we visited the legendary Makgadikgadi meerkats, humanised through behavioural research and unfazed by us, our trouser legs doubling up as watchtowers.

Then it was back in the saddle again and into the Kalahari. The guides, Lebius and Gideon, chuckled at my unfiltered reaction to the vast and haunting beauty of the pans in daylight. We cantered skirting the edge of the shallow water reflecting the noon-day sun. Puzzled wildebeest raised their heads, vultures looped the palm trees ahead, springbok grazed and the dazzling lilac breasted roller stopped us in our tracks.

I spent my final evening with the San bushmen, the oldest tribe in southern Africa. Their near-extinct way of life is finely tuned to nature and couldn’t be further from my iPhone-obsessed one. I needed to remember that moment. As the sun set in crimson jamboree across the pans, I tightly gripped my last G&T, reluctant to let that cathartic feeling go. The trip of a lifetime is an overused phrase, but occasionally the right one.

Jack’s Camp