Track & Trace: The Origins of Coloured Gems

By

4 years ago

‘This industry has to wake up to its impact on the planet’

Avril Groom investigates how the jewellery industry is cleaning up the murky world of coloured gems.

Chase the Rainbow: Colourful Jewellery

Track & Trace: The Origins of Coloured Gems

Four years ago, Caroline Scheufele, co-president of Chopard, which has a deep commitment to sustainable and ethical production, told me that tracing the origins of coloured gems was ‘still a nightmare’.

Diamonds, mainly in the hands of big industrial firms, have cleaned up their act, but coloured gems are different. A much more fragmented industry, there are a few big players who can control conditions and distribution, such as Gemfields (on emeralds and rubies) and Fuli (on peridots) but it is still substantially dependent on an age-old system of small-scale artisan miners and dealers who know each other well, relying on handshakes and trust rather than blockchain ledgers. In some regions, politics, conflict and dubious finance still enter the equation, and the old image of the intrepid gem hunter risking life and limb still has some truth.

But clients today want reassurance not only that their gem is exactly what it says on the tin but that it has been mined and processed in sustainable, ethical conditions. Strides are being made, with high-tech tracking of individual gems from mine to maker now available. It’s currently business to business but it will shortly extend to the consumer. But can technology ever replace trust, and how long will this take?

Analysing stones for authentication goes back a century, when the Gemological Institute of America and Switzerland’s Gübelin Gem Lab started setting standards, which they still do – the latter’s Provenance Proof technology can identify the source of many stones by their ‘chemical fingerprint’, and pinpoint treatment such as heating that affects value.

But a supply chain that may include up to 30 participants needs full traceability such as blockchain, says GemCloud’s COO, Philippe Ressigeac. GemCloud is a software that records online every transaction involving the stone and rejects a sale if the owner is not registered.

‘Blockchain’s advantage is that it cannot be tampered with once an entry is made by a registered person,’ says Daniel Nyfeler, managing director of Gübelin, ’and it is already used in reduced circumstances – all it needs is the internet and a smart phone.’

Meanwhile, membership of the watchdog Responsible Jewellery Council is mushrooming and although many of the movement’s initial leaders were smaller independents, the major luxury companies – which in the past, points out Philippe, guarded their coloured stone sources from competition – are now fully signed up to the concept. Some of the biggest, including Tiffany & Co., Swarovski, Richemont, LVMH, Kering and Gemfields, created the Coloured Gemstone Working Group (CGWG) in 2015, which offers help and advice on achieving sustainability and transparency to any company at any level of the industry, large or small.

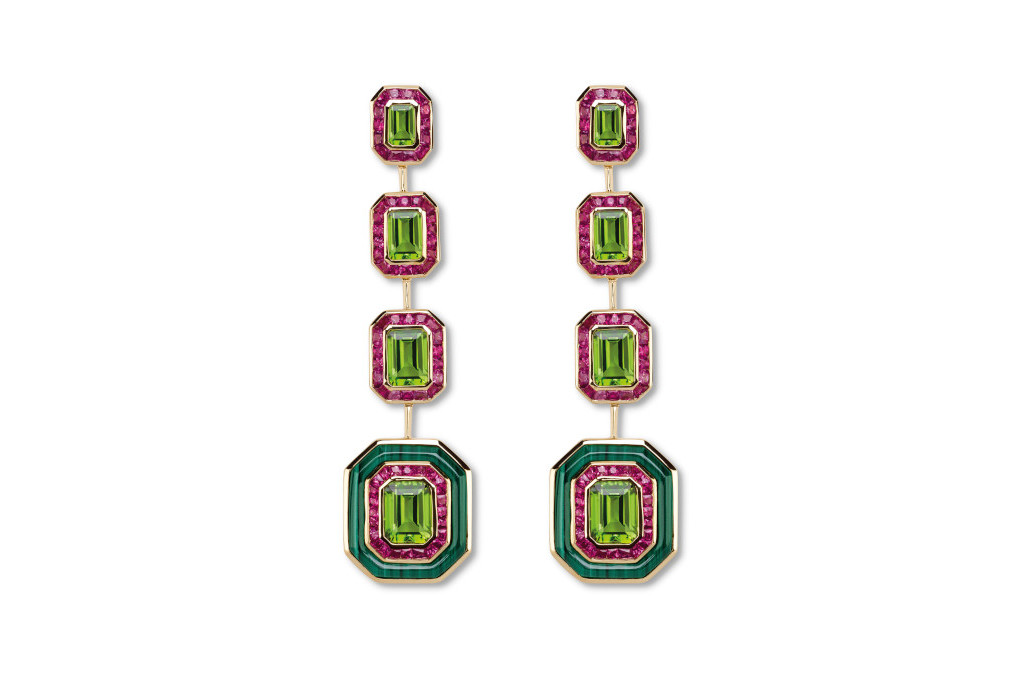

Annoushka x Fuli Gemstones Radiance collection 18ct gold and peridot earrings, £28,000

These threads are drawn together in new websites Gemolith (from GemCloud) and Gembridge, which offer stones online, currently to jewellers but eventually direct to consumers, with a fully transparent history of the many hands they have passed through.

‘The mine-to-finger process matters to today’s consumer, especially if it is from an artisanal mine,’ says Daniel, who supplies Gübelin’s analyses to Gembridge. ‘They ask if their stone has a negative environmental impact, or is funded by conflict, and until recently it was hard to answer.’

He explains how sub-microscopic nano-particles containing a stone’s data can now be coated on. It’s expensive, so best for high-value stones, but is also balanced by software like GemCloud, which, according to Philippe, is designed to be ‘very simple and affordable; it’s already being used by mining families in Sri Lanka and women’s mining co-operatives in Madagascar.’

Coloured gem prices, including varieties formerly labelled ‘semi-precious’, have risen exponentially – Philippe estimates up to 1,000 per cent in the past decade, fuelled by new demand from China. Big companies, which must submit to exacting scrutiny, have jumped in as never before, allowing tightly controlled gems like Fuli peridots or Greenland rubies to come to market and attract top designers, such as Annoushka with her peridot suite or Pomellato, which chose Greenland ruby for its Nuvola Earth Day ring in Fairmined gold.

Pomellato Nuvola Earth Day ring, £17,300

‘This industry has to wake up to its impact on the planet’, says Fuli’s UK director Pia Tonna. ‘The company has a licence from the Chinese government, is almost vertically integrated, including using its own hydro-electric power, and is independently audited for sustainability. There are also industrial by-products – local people welcome the employment opportunities.’

Greenland rubies are heat-treated to enhance colour and durability. ‘We are proud to acknowledge the effects this achieves; it’s part of our commitment to transparency,’ says CCO Hayley Henning. ‘It’s taken decades to agree mining licences with the Greenland government to create a modern enterprise that doesn’t just take but is part of the community.’

The high-tech process depends mainly on geologists and engineers, some trained locally, ‘because local people understand how to work in the climatic and light conditions of the high Arctic’. Cutting and polishing take place in Thailand, where the company controls the process. It has also founded the PinkPolarBear Foundation, helping not just conservation but to preserve Inuit culture.

Despite the positives, traceability is a slow process, and the old ways still have a place. ‘Remote areas may lack power or internet so dealers have to handwrite the transaction, and some artisan miners cannot read, so there has to be trust,’ says Philippe.

Boodles Havana ring with pear-shaped orange diamond, rock crystal and white diamonds, £POA

For most jewellers, trusted sources remain as important as high-tech traceability. Boodles’ director Jody Wainwright, whose grandfather was a noted gem hunter, commemorated in the brand’s latest high jewellery ring collection, says, ‘on the one hand we are working with high-tech tools like Gembridge, while on the other we rely on personal links, such as a trusted dealer in Sri Lanka who acts for about 20 artisan sapphire-mining families. These links go back generations and are invaluable.’

Even those who help formulate traceability policies are realistic. Assheton Carter, CEO of TDi Sustainability, has spent decades on this, and says, ‘there needs to be a balance. Conditions in some areas may not seem ideal, but if we can ensure that small artisan mines are safe and clean and demonstrate that they can meet regulations and still be profitable, that’s progress’.

Julianne Moore wears a necklace from Chopard’s Green Carpet Collection featuring the first responsibly sourced Paraiba tourmaline

Caroline at Chopard agrees. ‘There is still a long way to go to improve sustainable practices but initiatives like the community platform make a big difference,’ she says. The consumer message is optimistic: do some research and have confidence in today’s glorious-coloured gemstones.

Featured image: The Fuli Gemstones peridot mine in China

The Emerging British Jewellery Designers to Watch Now