A Matter of Faith

By

3 years ago

Sally Jones reports on those schools which offer a distinctively spiritual side

For many, the idea of faith schools conjures visions of strict, cloistered convents or monasteries run on spartan lines, with hours of obligatory worship each week. Among the Anglican foundations, the image seems more the muscular Christianity of Tom Brown’s School Days, Thomas Hughes’s fictionalised account of Rugby School in the 1830s under pious Dr Thomas Arnold.

These days, however, whatever their religious affiliation, most major schools attract youngsters from scores of different nationalities and from a wide range of faiths and none, so earlier generations’ didacticism and expectation of unquestioning belief are no longer options. Many once-religious schools now tread a careful path, avoiding any hint of dogma in their assemblies and teaching for fear of alienating those from other backgrounds. Others, however, remain devoted to spreading the word about the faith which forms their USP and are finding new markets, even among non-believers.

According to a recent survey by theology professor Stephen Bullivant, just seven per cent of young people in Britain now identify as members of the Church of England while 10 per cent embrace different sects within Catholicism, partly thanks to immigration from traditionally Catholic areas such as Poland and Latin America.

Although most faiths are experiencing a decline in numbers of worshippers and ageing congregations, faith schools remain popular with parents. So what is their appeal in an increasingly secular society?

At St Benedict’s, a renowned co-educational school in Ealing, West London, about half the children are not Catholic but according to the headmaster, Andrew Johnson, the message of this Benedictine foundation with its daily prayers, regular masses and commitment to service remains as potent as ever.

‘Forty years ago, families would send their children to a school like ours just because it was Catholic,’ he explains. ‘These days, faith schools need to be very good, academically and pastorally, and because faith is not a certainty for anyone, we meet people where they are.

‘There’s no let-up in interest in our school: in an individualist, unforgiving, secular world, families, whether Sikhs, Muslims or of no faith, find our values attractive and nurturing.’

He points to the school’s sense of environmental responsibility reflecting the Pope’s strictures on care for the natural world. ‘A small group from here took a signed petition to 10 Downing St,’ he says, ‘urging the Prime Minister ‘Be Bold Boris!’ and focusing awareness on COP26.’

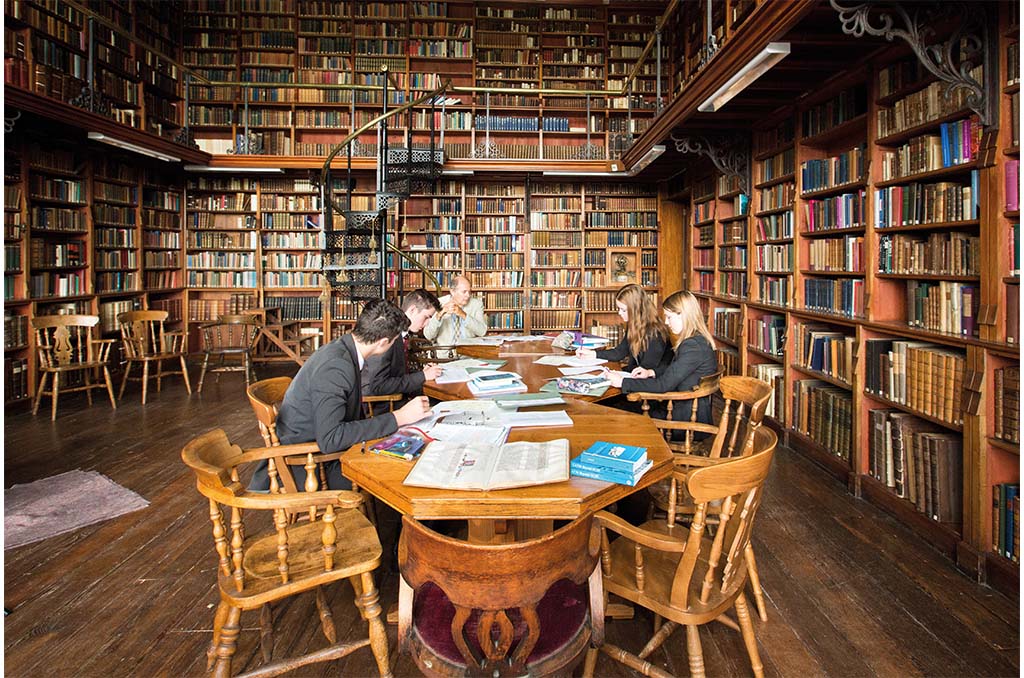

A long way north, spectacular Stonyhurst College in Lancashire’s Ribble Valley is the oldest Jesuit school in the world.

Here, as at St Benedict’s, faith is equally central to day-to-day life, whatever a pupil’s religious background. Saint Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus, called Jesuits to ‘Go forth and set the world on fire’ and with its motto Quant je puis (As much as I can), Stonyhurst’s pupils are encouraged to develop their unique talents, for the good of society.

‘Like all children in Jesuit schools, our pupils write AMDG, for Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam (For the greater glory of God) at the top of every piece of their work,’ explains Ian Murphy, headmaster of the foundation’s prep school, Stonyhurst St Mary’s Hall, ‘and LDS, for Laus Deo Semper (Praise God always) at the end. This tradition sets the tone of each pupil striving to do their best in everything they do.’

Murphy explains: ‘We challenge everyone to live out their faith in practical ways, from Lenten ‘fast’ lunches to becoming ‘men and women for others’ through our extensive voluntary service programme.’

Stonyhurst’s values-led education is based on the Jesuit Pupil Profile, eight pairs of character-forming virtues to which students should aspire: such as being grateful and generous and eloquent and truthful. Ian Murphy believes these precepts change lives.

‘We recognise each child’s uniqueness and support a number, often from challenging backgrounds, on bursaries,’ he explained. ‘We have two driven, streetwise girls from London on bursaries, both academic high-flyers, one a Muslim from a Somali background, and they’ve become hugely involved in the life of the school.

‘Our focus is not on how many ‘Hail Marys’ are said but about nurturing active, compassionate people. These girls identified quickly with ideas of social justice and fundraising: during work on the COP26 agenda, one was inspired by a young climate activist and now wants to be a campaigning eco-journalist herself. This is not the girl who arrived here a year ago.’

What a Jesuit education does, he adds, is give non-Catholics ‘an accessible gateway into faith through living and learning.’

Worth School, set within Worth Abbey and its 500-acre park in West Sussex, is run on Benedictine principles, with weekly whole-school worship and regular Masses. Building on St Benedict’s belief that caring community life was essential to knowing and passing on God’s love, the school has distilled his vision into six values permeating every area of school life: humility, stewardship, worship, silence, community and service. Social action is a major aspect of this. Pupils support charities, particularly Mary’s Meals and Justice Defenders, while the Chaplaincy pupil leadership team has led a ‘Sleep out to help out’ campaign, fundraising to increase awareness of youth homelessness.

Stuart McPherson, Worth’s headmaster, believes that families are drawn to the school for its strong academic credentials as well as the spiritual ethos which values their children deeply as individuals.

‘Catholics and other Christians are looking for faith to be nurtured and perhaps seeking safe harbour from a culture that is often explicitly or implicitly sceptical of faith positions,’ he said. ‘Parents from other religions, or none, feel that Worth is a safe place where their children will encounter a beautiful, enriching culture, which respects their own beliefs.’

Silence and contemplation likewise play a central role in Britain’s handful of Quaker schools, such as Sibford in Oxfordshire. Since their formation in the 17th century, Quakers have worked to achieve social justice and a more just and equal world. Sidcot School, Somerset, boasts a Centre for Peace and Global Studies while Leighton Park in Reading focuses on ethical enterprise, following the example of successful Quaker businesses, such as Rowntree, Cadbury and Barclays Bank. Through creating social good as well as profit, the Leighton Park has won the Independent Schools Association Award for Outstanding Local Community Involvement for the past two years.

In the schools, everyone uses first names terms and assemblies are non-hierarchical, held in the round, mostly in silence, At Leighton Park where only five pupils are Quakers, the entire school follows the distinctive practice.

‘The idea is to connect with the voice of God (or good) inside you,’ explains Director of Marketing John Burnett. ‘One example is sports fixtures. At half time, the first XV have a huddle and a moment of silence. As in our meetings, if anyone feels moved to say something, they can, whether its gratitude for their friends’ support or what great tackles someone has made. Our students are caring and positive with each other – it makes the school very special.’

Each faith school has its own sacred space, but few are as majestic as the great chapel of Lancing College, beaming out across the Sussex Downs. The flagship of a chain of Church of England schools, Lancing was founded in 1848 by Nathaniel Woodard, a local curate who told his young charges, ‘The success of society rests on your shoulders alone,’ and believed that a strong moral foundation was crucial to a transformative education.

These days, the message is as powerful as ever. Service is central to Lancing’s ethos, whether fundraising for the school’s longstanding Malawi project or volunteering in the local community, and the chapel with its regular whole-school services and time for private reflection remains a potent centre of worship. Many non-Christians take inspiration from serving there, including one of the heads of school, Shirin, an agnostic from a Muslim background.

‘As Head Sacristan at Lancing,’ says Shirin, ‘I’ve experienced the opportunity to understand the Christian faith from a different perspective.

‘Lancing has given me the opportunity, through sacristans and chapel services, to be able to view how faith can have such big impacts on people.’

The chance for some quiet reflection for pupils – when they’re not using mobile phones or social media – is very useful, says Senior Deputy Head Hilary Dugdale. ‘Being among everyone creates a strong expression of community, an amazing drawing-breath moment amid a hectic 21st century education. When they leave school, most are ambitious intellectually but also think ‘What can I do, what can I give back?’ They’ve imbibed that sense of service along with the religious experience.’

Despite contrasting styles of worship within the different faith schools, there are striking parallels between the message and ethos which each radiates to the world. Families choosing this type of education for their children describe the sense of the numinous and the strong spiritual and moral dimension which it inculcates, radically influencing them for life.

Ian Murphy from Stonyhurst could be speaking for them all in his assessment of his own school’s role and value in the world: ‘Pope Francis washed the feet of inmates in a Rome prison, a wonderful thing to do,’ he observes. ‘Like him, we should be saying to the world ‘I’m here to serve, not judging you.’ Our faith values: fairness, social justice and kindness are very much part of day-to-day experience here and our people carry those with them.

‘These equip them to engage well with others and develop the soft skills that are so important in their work and family lives.’

READ MORE FROM SPRING SUMMER 2022

Choir Power | Music to Our Ears