How can we teach our children the importance of a good relationship with food?

By

7 years ago

The founder of Isa Robinson Nutrition and registered associate nutritionist (ANutr) Isa Robinson, is currently based in London where she works with clients experiencing disordered eating. Having struggled with her own issues with food as a younger teenager, she is passionate about promoting the mutual importance of how we think and feel about food, as well as what’s on our plates. Isa has a masters in eating disorders and clinical nutrition from UCL with distinction and is also an ambassador for the UK’s leading eating disorder charity BEAT.

Isa launched her blog Goodness Guru in 2014 after her first year at the University of Edinburgh. She is aware that, as is the case for many young girls, the pressures of teenage life contributed to her becoming a very image conscious teen. Given her own toxic relationship with food in the past, Isa aims to promote the joys of eating free from guilt and restriction. Balance is central in not only her own approach to health, but to her writing and the views expressed on her blog.

There is a juxtaposing public health problem in question. Childhood obesity is at a record high, yet simultaneously so are hospital admissions for eating disorders in children and adolescents, a disease with the highest mortality rate of any mental illness. Studies support that children are increasingly fearful of becoming fat, and that one third of boys, half of young girls and two thirds of older girls are trying to lose weight. Whilst the question of obesity is at the forefront of public health, an equally sinister issue is brewing, for never before have we as a population been so dissatisfied with the way we look. This has also trickled down to our children.

A far cry from hide and seek, kids are growing up in a parallel universe of social media, where emphasis on image and appearance are of increasing importance. Children as young as eight are desperately seeking validation, posting pictures of themselves on the internet asking ‘Am I ugly?’ As though their sole purpose on earth is to live up to the ideals of beauty imposed by society.

The rise of wellness in London in the last five years, whilst perhaps with good intentions, hasn’t done so much for our health as it has for our plummeting self-esteem and bank statements. We have become a nation of picky eaters, whereby the size of our bodies and our perceived ‘health’ determines our moods and where guilt, anxiety and stress have become ubiquitous qualities in our behaviour around food.

As a young child, my mum would have a toffee crisp waiting in the car for me after school. Peeling open the orange cellophane wrapper and crunching the puffed rice encased in always slightly melted chocolate between my teeth was one of my happiest afterschool rituals. This was a time in which restrained eating and the concept of being fat or ‘healthy’ were alien to me. It was simply a moment of pleasure and a special bond between mother and daughter. I was lucky my mother was able to cook us balanced meals as children, although we did always have McDonald’s on a Friday lunchtime (I seem to have turned out ok). She did occasionally dibble dabble with the Atkins diet, which I suppose I was quite aware of, but otherwise there was never any anxiety or over importance bound up in food and meal times. It was always a source of great pleasure and coming together as a family.

Now, the trend is cut the gluten, slash the dairy and cull all refined sugar. Processed food is said with such distain it might as well be a mouthful of dirt and god forbid we serve up anything made with GMO. And whilst the yearn to take our health seriously is no bad thing, have we gone too far? And more importantly, what do the effects of intermittent fasting, juice cleanses and low carb diets have on our children?

Ironically, a new born child knows how to eat better than we do. An infant will scream when it’s hungry and turn away when full. Forget structured meal times and prescribed rules, a baby is totally able to self-regulate, free from the grip of diet culture, emotional eating and its dress size.

Yet as our bubbas grow up it’s us adults that complicate the picture. Food becomes a reward or comfort, dessert a bribe to eat vegetables and there is usually praise for finishing one’s plate. We undo a child’s ability to eat intuitively and by the time they can swear, read magazines or hold an iPhone, food is a convoluted ordeal, deeply implicit in the ever-tiresome quest for thinness. In a world of food abundance, scaremongering and obesity, trusting our children’s primal eating cues isn’t easy and nor is being a good role model when our own relationship with food isn’t exactly hunky dory!

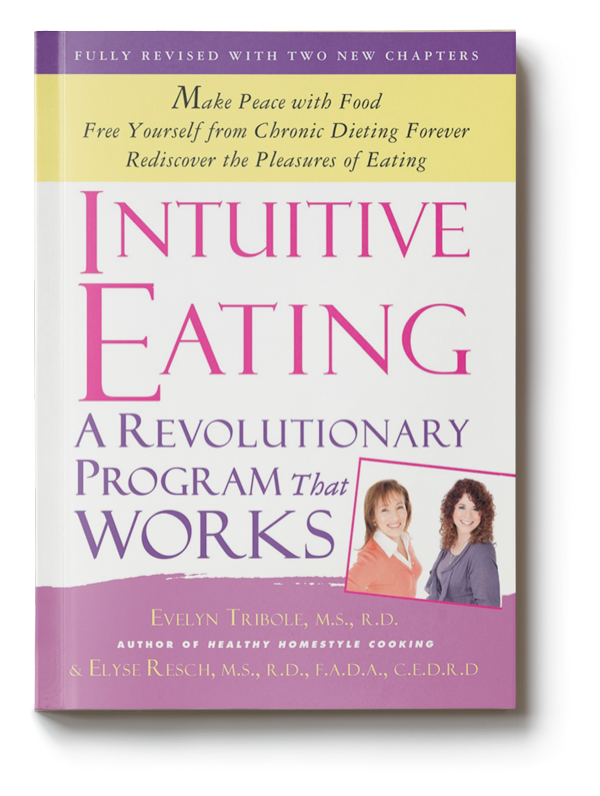

So what can we do? Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch, authors of my most favourite book Intuitive Eating, highlight many ways in which we can support our children and help them find a balanced approach to food.

They stress the importance of trusting our children in their food choices, offering a wide variety of foods including ‘play foods’ when appropriate, as well as all the nutritious stuff. ‘Play food’ is what the authors use to describe foods that simply taste good and bring joy in the same way as playing. These foods, so often overlooked through a nutritional lens, can actually serve great purpose when enjoyed in moderation and free from guilt. Depriving your children of sugar, sweets and other play foods will likely backfire; there’s never any prizes for spotting the child at a party who has never seen sprinkles and maltesers before.

Tribole and Resch also highlight the need to get messy in the kitchen and to include children in food preparation and cooking right from the get go. To ask children if they’re hungry and when they are full, and what these essential signals feel like in the body. Of importance to note however, is that eating well shouldn’t simply boil down to eating when you’re hungry and stopping when you’re full, but that sometimes it’s ok to overdo it too and that this doesn’t mean penance through restricting or exercising food off the next day. Lastly, to move away from dichotomising between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ foods, which only make us feel guilty when we eat the latter and to teach our children about managing emotions such as grief, anger and boredom without need for food.

Of course, the book goes into much more detail with reference to topics such as managing overeaters or difficult adolescents. However, the core message remains consistent: the need to move away from seeing food as the sum of calories and nutrients and working on our relationships with food and how it makes us feel as humanbeings. The call to connect with our hunger and fullness signals and fully enjoying the experience of eating free from guilt and judgement.

To end, I want to touch on the government’s new 100 calorie snack ‘change 4 life’ campaign, which promotes giving children a maximum of two 100-calorie snacks per day to encourage healthier snacking – that’s farewell to my beloved toffee crisp then!

Despite obesity and its associated risks, what does this message really teach our children about their relationship with food, nutrition and health in the long term? And is calorie counting something we really want to be teaching our children at all? Where does this leave helping youngsters to tune into their hunger and fullness signals and helping them with gentle nutritional education and the joy of cooking and eating? In short, nothing! Perhaps for the sake of future generations it is time for a more radical approach that teaches children to value themselves beyond their physical appearance and practice a healthy and balanced relationship with food.

By Isa Robinson, Isa Robinson Nutrition

Intuitive Eating is available to buy here.